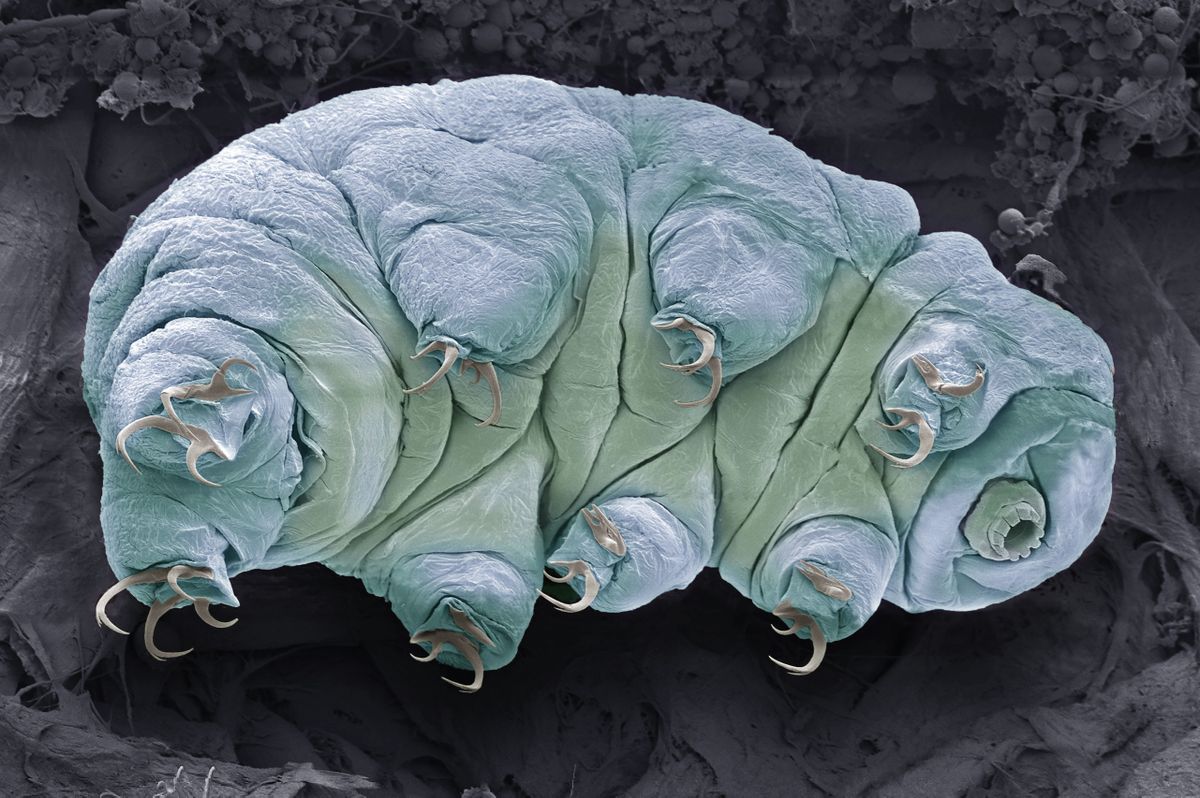

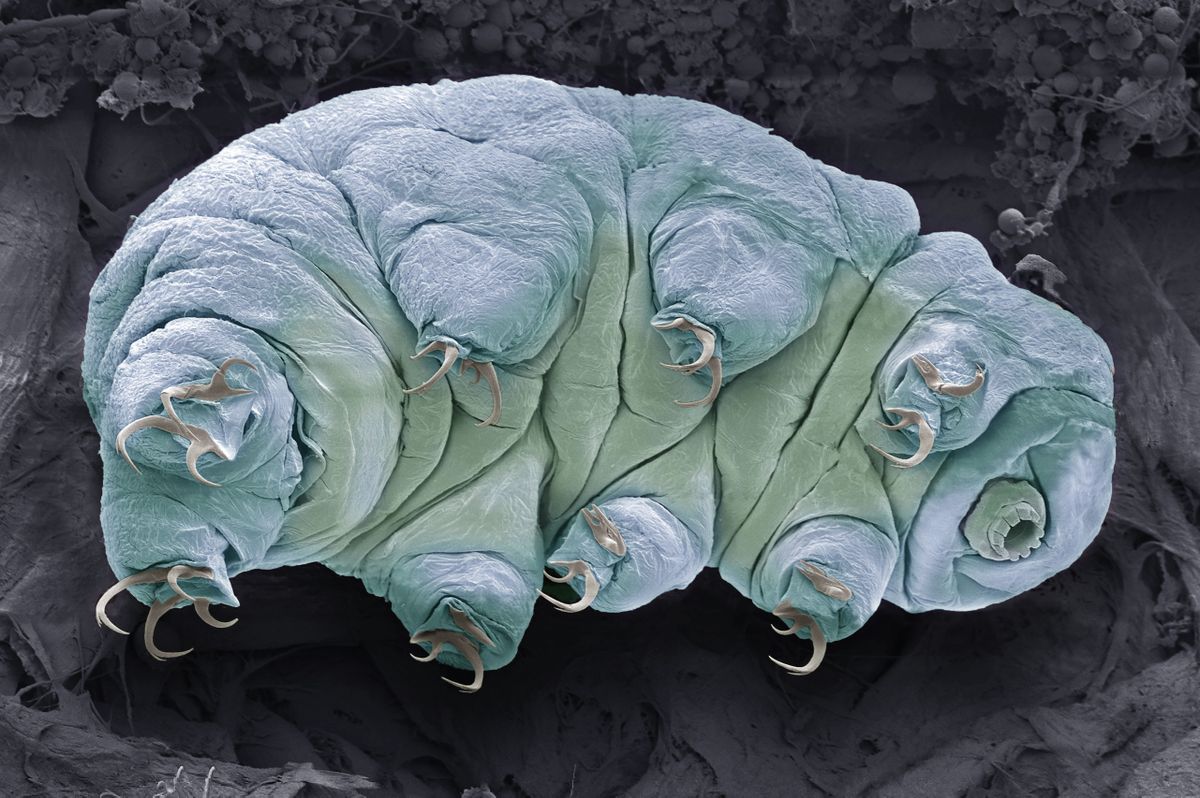

Tardigrades, those tiny, plump-bodied creatures affectionately known as "moss piglets", have been put through the ringer for science. The amazingly durable creatures have been shot out of guns, bathed in boiling-hot water, exposed to intense ultraviolet radiation and even crash-landed on the moon to test their survival mechanism.

Researchers are trying to see if a frozen tardigrade can be incorporated into two quantum entangled electric circuits, and if moss piglets can survive the highest pressures that have ever been encountered.

The results of a new paper suggest that scientists may be able to add "temporary quantum entanglement" to the tardigrade's growing list of accomplishments. The paper's early responses have raised issues with the finding.

This experiment will be the first time a living animal has been quantum entangled, and it will be done if the findings survive peer review.

Tubby 'tardigrade' crawls across the sun's surface.

Albert Einstein had doubts about the phenomenon of quantumentanglement, which he dubbed "spooky action at a distance." The effect occurs when two tiny particles are bound to one another so that a change in one particle's spin or momentum instantly changes the other particle in the same way.

Scientists tried to prove that this effect could be able to go beyond the realm of the subatomic particles. Live Science previously reported that a team found that certain photosyntheticbacteria were able to become entangled with light when the light's resonance in a mirrored room synchronized with the frequencies of electrons in thebacteria's photosynthetic molecule.

The authors of the new arXiv paper decided to test the relationship between a multicellular organism and a single celled creature. The team collected three tardigrades from a roof gutter. The tardigrades were frozen and sent into a tun state, which shrunk them to about a third of their original size.

The tardigrades were frozen further, cooling them to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero, which is the lowest temperature a tardigrade has ever been exposed to.

The team placed each frozen tardigrade between two plates of a superconductor circuit that formed a quantum bit, a unit of information used in quantum computing. The qubit's resonance was shifted when the tardigrade came into contact with it. The two qubits became entangled after that tardigrade-qubit- hybrid was coupled to a second nearby circuit. The researchers saw that the frequencies of the qubits and the tardigrade changed in tandem, like a three-part entangled system.

The researchers warmed the tardigrades up in an attempt to revive them. One of the tardigrades came back to its previous state, while the other two died. The researchers claimed that the survivor is the first quantum entangled animal in history.

"While one might expect similar physical results from objects with similar composition to the tardigrade, we emphasize that the entire organisms that retain their biological function after the experiment is what we mean by 'entanglement'," the team concluded in their paper. The tardigrade was exposed to the most extreme and longest conditions it has ever been exposed to.

The paper has not yet been peer-reviewed, but early responses from the scientific community have been critical. The experiment did not entangle a tardigrade with a qubit in any meaningful sense, according to the Department Chair of physics and astronomy at Rice University.

The authors put a tardigrade on top of one of the two qubits. The tardigrade is mostly frozen water, and it acts like a dielectric, shifting the resonance of the one qubit that it sat on.

Ben Brubaker is a science writer.

The qubit is an electrical circuit and putting the tardigrade next to it affects it through the laws of electromagnetism we've known about for more than 150 years. A small amount of dust next to the qubit would have the same effect.

The study shows that moss piglets are even more durable than previously thought, even if the tardigrade did not experience any "spooky action" from the qubits it was attached to. This experiment should serve as a reminder that regular-old tardigrades are interesting on their own.

Live Science published the original article.