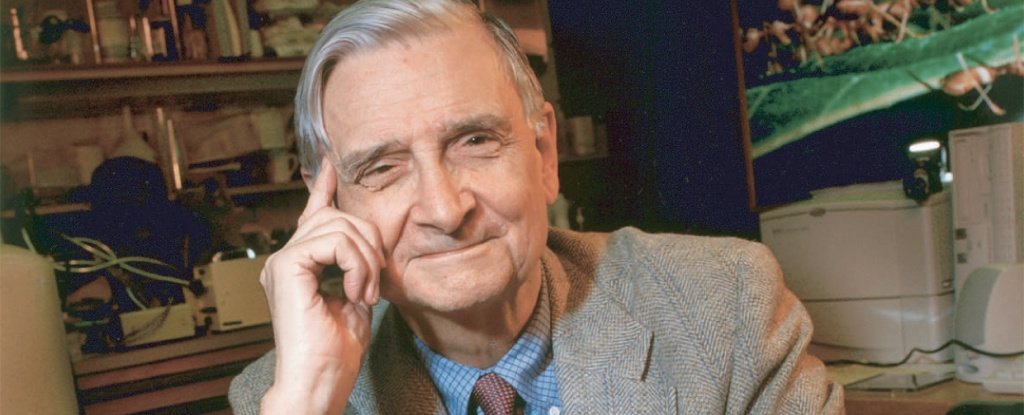

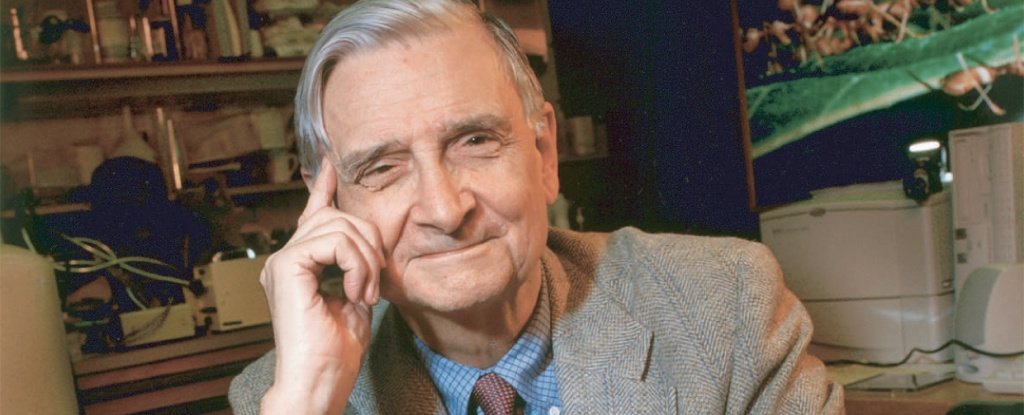

E. O. Wilson was an extraordinary scholar. The chair of the biology department at the University of Delaware told me in the 1980s that a scientist who makes a single seminal contribution to his or her field has been a success.

Edward O. Wilson made at least five contributions to science by the time I met him.

Wilson, who died at the age of 92, discovered the chemical means by which ants communicate.

He looked at the importance of habitat size and position within the landscape.

He was the first to understand the evolutionary basis of both animal and human societies.

He was an academic god for many young scientists like me because of his seminal contributions.

His ability to piece together new ideas using information from different fields of study may have been the reason for his amazing record of achievement.

Insights from small subjects.

I sat next to the great man in 1982 at a small conference on social insects. He extended his hand and said, "Hello, I'm Ed Wilson." I don't think we've met. We talked until we got back to business.

I approached him again three hours later without fear because we were now the best of friends. He extended his hand and said "Hello, I'm Ed Wilson." I don't think we've met.

Wilson showed that he was a real person and compassionate even though he was forgetting me. I was fresh out of graduate school and didn't think another person at the conference knew as much as I did. He extended himself to me twice.

Thirty-two years later, we met again. I was invited to speak at the ceremony to honor him with the Benjamin Franklin medal. Wilson's many efforts to save life on Earth were honored by the award.

Wilson's descriptions of the many interactions among species inspired my work on native plants and insects, and how important they are to the food web.

Wilson's early writings provided a number of testable hypotheses that helped guide my research into the evolution of insect parental care. His 1992 book, The Diversity of Life, was the basis for a career turn for me.

I did not know that insects were the little things that run the world until Wilson explained it in 1987. My understanding of how biodiversity sustains humans was very little. Wilson opened our eyes.

Natural history, the study of the natural world through observation rather than experimentation, was not unimportant according to Wilson. He said that he needed to study and preserve the natural world.

He knew that our refusal to acknowledge the Earth's limits, coupled with the unsustainability of economic growth, had set humans well on their way to ecological oblivion.

West Africa's Upper Guinean Forest was deforested from 1975 to 1973. The USGS.

Humans' reckless treatment of the ecosystems that support us was a recipe for our own demise. The sixth mass extinction in Earth's history was caused by us, the first one caused by an animal.

A vision for the future.

E. O. Wilson added a second passion: guiding humanity toward a more sustainable existence.

He knew that he had to write for the public, and that one book wouldn't suffice. Learning requires repetition, and that is what Wilson said in his final plea, Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life.

desperation and urgent replaced political correctness in Wilson's writings as he aged. He challenged the central dogma of biology, showing that it could not succeed if it was restricted to small patches of habitat.

In Half Earth, he said that life can only be sustained if we preserve the functioning of at least half of planet Earth.

Is this possible? Almost half of the planet is used for agriculture, while 7.9 billion people and their infrastructure occupy the other half.

The only way to realize E. O.'s lifelong wish is to learn to coexist with nature at the same time. It's important to bury the idea that humans and nature are not the same. For the last 20 years, I have been trying to provide a blueprints for this radical cultural transformation.

There is no time to waste. Wilson once said, "Conservation is a discipline with a deadline." It's not clear whether humans have the wisdom to meet that deadline.

Professor of Entomology at the University of Delaware.

The Conversation's article is a Creative Commons licensed one. The original article can be found here.