A study found that a sugar Additive could have helped spread a superbug around the US.

The sugar trehalose found in foods such as nutrition bars and chewing gum is blamed for the blame.

If the findings are confirmed, it's a stark warning that even seemingly harmless Additives have the potential to cause health issues when introduced to our food supply.

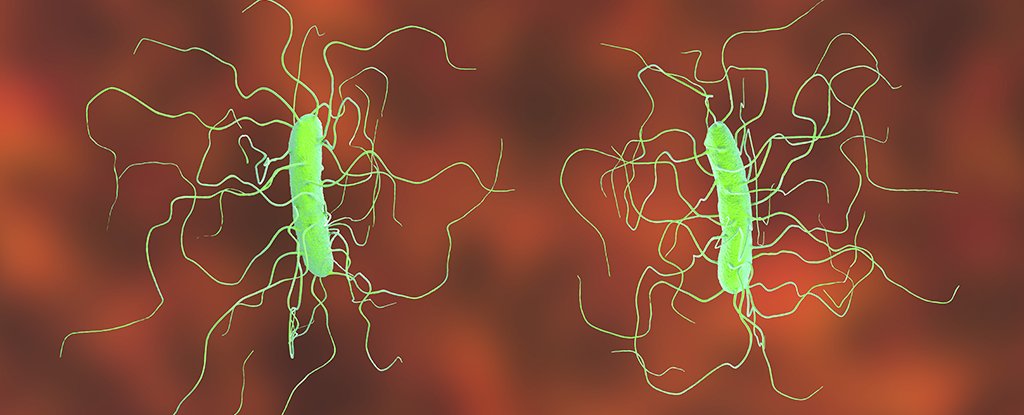

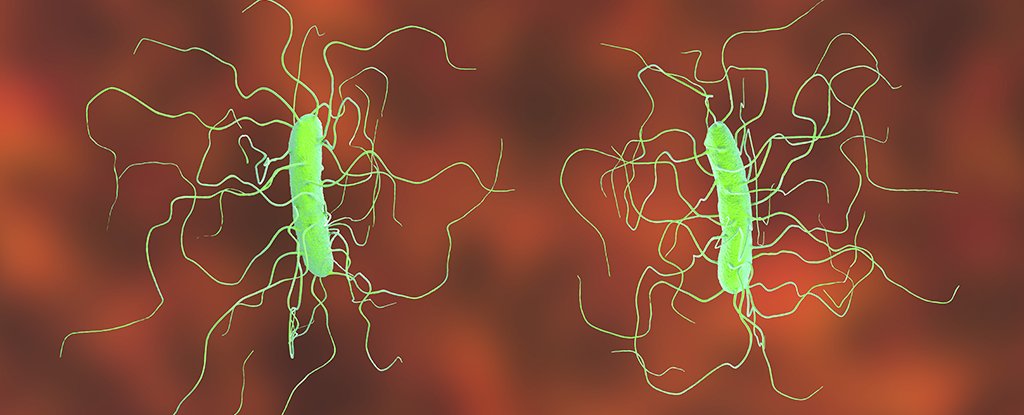

trehalose is being linked with the rise of two strains of the Clostridium difficile, a bacterium that can cause death.

The arrival of trehalose coincides with the rise of the antibiotic-resistant bug, which has become a huge problem for hospitals in recent years.

trehalose was approved as a food Additive in the United States in 2000 for a number of foods from sushi and vegetables to ice cream.

The reports of outbreak with these lineages started to increase over the next three years. Other factors may contribute, but we think trehalose is a keytrigger.

The C. difficile lineages are referred to as RT027 and RT078. The researchers found that the two strains had the ability to feed off trehalose sugar very efficiently.

The particular types of C. difficile need about 1,000 times less trehalose to live off than other types.

The scientists tested the findings with mice. The scientists found that the death rate was higher in the group given low doses of trehalose because of the sugar.

Testing on fluids from three humans showed that the strain ofbacteria known as RT027 was able to grow from small amounts of trehalose.

The study results and the timing of its approval as an Additive are pretty compelling, but it's not certain that trehalose has contributed to the rise of C. difficile. More research is needed to confirm the link.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that C. difficile was responsible for half a million infections and 29,000 deaths in the US in 2011. Let's hope this new research can help us fight it.

James Collins from the Baylor College of Medicine says that the lineages have been present in people for years without causing major outbreaks.

"After the year 2000 they began to dominate and cause major outbreaks and in the 1980s they were not epidemic or hypervirulent."

The realization that sugar can have unexpected consequences is an important contribution to this study.

Nature published the findings.

The first version of this article was published in January.