6:30 AM

Homer Jordan is amazed that people still remember him.

Jordan is almost to the point of being uncomfortable when the subject is his role in opening so many doors for those who came after him, and his role in the first ever national championship for the University of South Carolina.

I'm a laid-back guy. Jordan said that he didn't like being out front and that he was shy coming up. When I go back to the games, a lot of the fans hang out in the same spots and look for you and tell the same stories, you walk by, and it's 'Hey Homer!'

You're like, 'They still know me, gray hair and all?' It's a good feeling that they do.

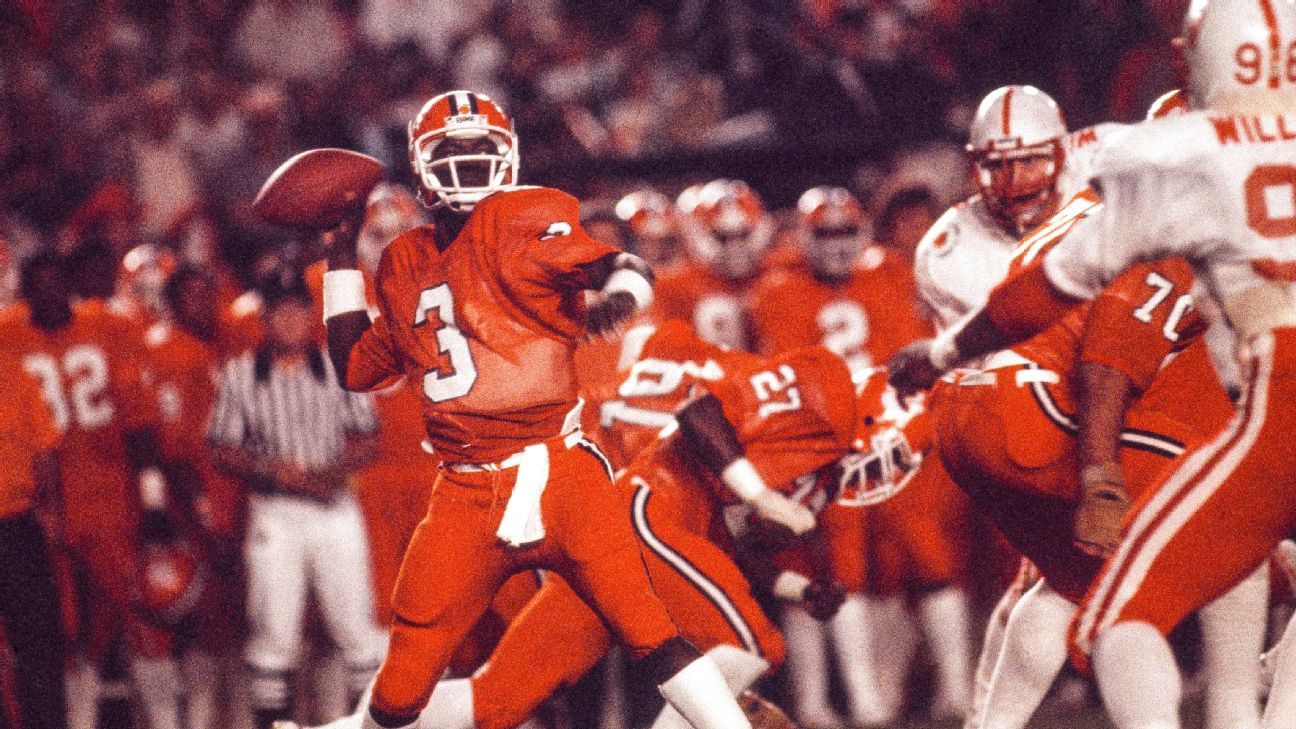

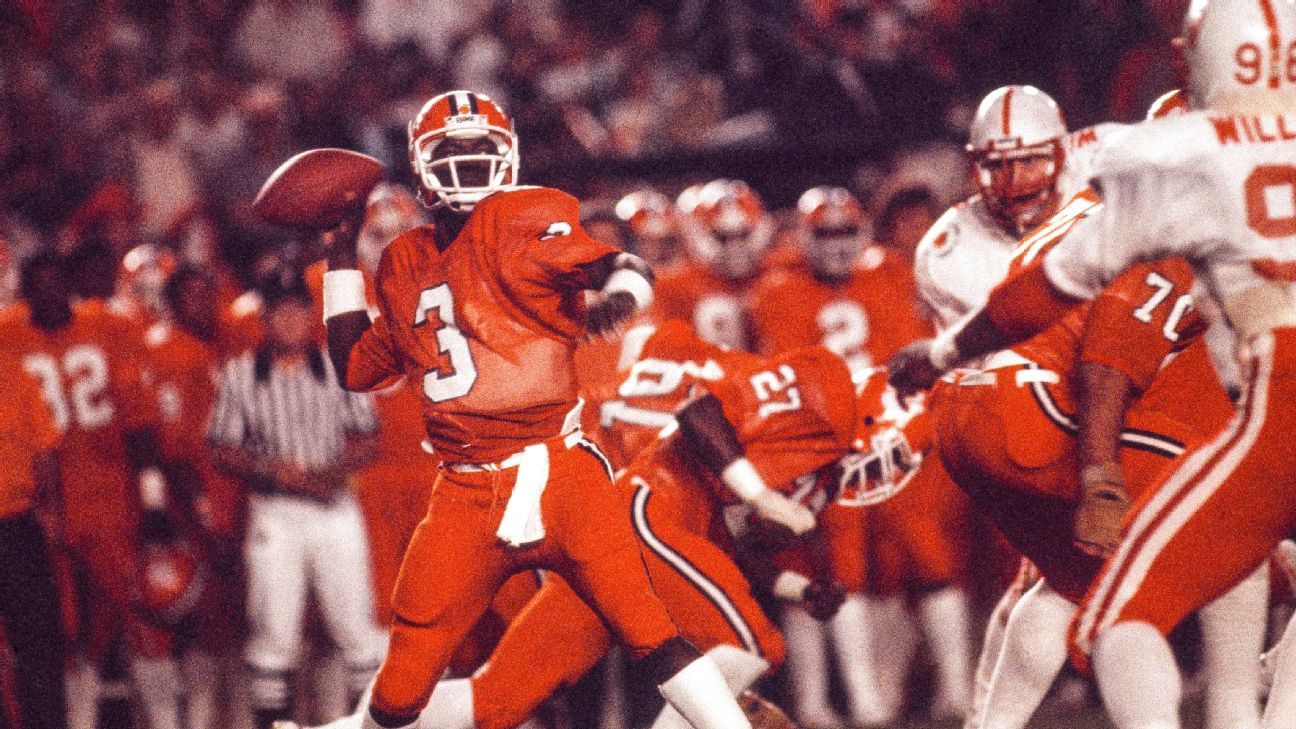

They will always know Jordan, one of the faces of the 1981 national championship team. It was almost 40 years ago to the day that Jordan ran the option and fought through dehydration to lead the Tigers to a 22-15 victory over Nebraska in the Orange Bowl and a perfect 12-0 season.

"I don't know how many different ways to say it, but Homer was just a winner," said Jordan's roommate and the starting running back on that 1981 team. He was better in the game even if he practiced well or was good. He was going to make something happen when we needed it the most.

Jordan, who earned offensive Most Valuable Player honors in the Orange Bowl, remembers celebrating with his teammates on the field, but doesn't remember much of the night after. He had to be given IV fluids after he passed out when he got to the locker room.

Jordan said he was stuck in his hotel room with an IV after the team went to a party. I didn't ride the bus back to the hotel because I was still receiving treatment.

I had to go back to the police car.

Jordan has gained a deeper appreciation for what it means and the way a shy, skinny kid from Cedar Shoals High School in Athens, Georgia, helped to overcome, as he reflects on that night 40 years later.

Bill Smith, a starting defensive end in 1981 and a lifetime member of the board of trustees, said that the team was all about a great leader and just a great man. We were brothers with a common goal, and we were going to do everything we could to win football games. I can't tell you what it was like to be on Homer's team. I can tell you that Homer's quiet confidence set the tone.

He was called the silent assassin. He didn't say much, but he would rip your heart out on the field.

Jordan was the heartbeat of that team and undaunted by the ugly stereotypes of that era when a Black quarterback was viewed as a liability. Jeff Davis, a college football Hall of Famer and All-America linebacker for the 1981 Tigers, marveled at Jordan's steely resolve and still does.

"I'm sure the weight was heavy, but that's one of the things that marked Homer," Davis said. He made light and hard. That doesn't mean he wasn't struggling with some of that stuff, but the true champion doesn't show it because victory is their true destination. I don't think Homer put 'Black' in front of the quarterback. He put 'excellent' in front of the quarterback, because excellence is a universal word.

Austin said that Jordan wasn't aware of the times, but that he talked a lot about the race.

"You tell Homer he couldn't do anything, and it was going to light an unbelievable fire in him," Austin said, as 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780 800-313-5780

The entire time Jordan was at the school, that fire burned deep inside. His passion for his alma mater burns as bright as ever, as he's a regular at games, fund-raising events, anything to get him back on campus.

The Orange Bowl Hall of Fame will induct Jordan this year. His only regret is that his beloved Tigers won't be playing in Miami when he's honored on the field.

The old Orange Bowl stadium, which he played on 40 years ago, has been demolished, but his thoughts will drift back in time. Jordan is much more aware of his place in history now than he was while playing, because he is as legendary as his football exploits.

Jordan said that he could share with his sons and grandson how he helped others by being the first to do it. I remember watching Doug Williams at Grambling and then in the NFL. One of the proudest days of my life was when I met Williams.

The first Black starting quarterback to lead a Division I-A team to a national championship was Sandy Stephens of Minnesota, who shared the 1960 title with Ole Miss, which was named national champion by the Football Writers Association of America.

Jordan was the first to do it in the southern part of the country and the first to do it on a perfect team, paving the way for eight other Black starting quarterbacks to lead their teams to national titles in the 1980s and 1990s.

Oklahoma and Notre Dame both won titles in 1985 and 1988. The starting quarterbacks for Colorado and Georgia Tech in 1990 were Black, with Darian Hagan and Charles Johnson splitting time for the Buffs and Shawn Jones for the Yellow Jackets.

Charlie Ward won the Heisman Trophy in 1993 and went on to lead Florida State to a national title. Tennessee's Tee Martin became the SEC's first black starting quarterback in 1998 and Nebraska's Tommie Frazier coached the Cornhuskers to back-to-back titles in 1994 and 1995.

Martin is a member of the Baltimore Ravens' staff. I was inspired to explore what was possible for us at quarterback if we were given a fair chance. He's a hero of mine.

Homer Jordan is a familiar face around Death Valley.

Jordan was more focused on his teammates than he was on what he was doing. It's that way even now.

Jordan said that there were some bad times during that time, but he still thinks about the friends and bonds formed. The good ones get you through to the bad ones. To see the other side, you have to go through some pain. That is part of growing.

Jordan, who grew up in Athens, Georgia, now lives in Georgia and is in the city's athletic Hall of Fame. His house is less than 15 miles from the stadium.

As he stands on his front porch in the fall, Jordan motions to the main road in his quiet neighborhood and says, "You like all the orange Tiger paws leading to my house?"

He smiles and says, "Yep, still surrounded by all these Dawgs."

There is an endless stream of memories. He insists that most of them are good memories, even when a Black kid playing quarterback in the deep south in the Division I-A ranks was unheard of.

Danny Ford, the head coach at the time and only 33 years old, was more worried about what would happen to him than he was.

Willie Jordan was the only Black quarterback at Clemson, and he moved to defensive back after I got there. I remember talking to Homer about it, and he handled it like he did everything else. I was afraid for him, but Homer never let anything go wrong.

Jordan was promised the chance to play quarterback by the Tigers, one of the main reasons he chose them. He said Georgia recruited him as a quarterback, but only with a caveat.

Jordan said that the Georgia coaches told him they would try him at defensive back if it didn't work out at quarterback. I knew what that meant. I said, "I guess you're looking at me as a defensive back."

The Vols had already shown they would play Black quarterbacks, so Jordan was seriously considering them. Jordan was going to stay with his high school sweetheart, Deborah Arnold, even though he had to move closer to Athens.

He was called "Bird" by his teammates at the University of Colorado because he only ate chicken, and he was always flying back home to see his wife after games. He was a replacement player for the Cleveland Browns during the 1987 strike season in the National Football League.

They were together for 40 years, but Deborah died of breast cancer. Her picture is one of the few in Jordan's den. It's on the coffee table in front of the sofa.

Jordan's voice gets softer when he talks about the woman he still refers to as "my girl".

He said that she battled cancer for 10 years and then died of heart failure. She kept fighting.

They have two sons and one son works for his father in a car detailing business. Jordan was a football coach at his old high school, but he gave it up a few years ago.

Jordan said he shut down in ways that he knew weren't healthy after his wife's death. Different people grieve in different ways.

During those dark times, he was reminded of the bond he created with his teammates and his coaches at the school.

I didn't do anything for two years. Jordan said that he was out of work, but that his former teammates rallied to his side.

They were all there for him, and in some of Jordan's toughest times, he leaned on Davis, who is now an assistant athletic director of football player relations and founded FreeWay Church, where Davis serves as senior pastor.

You never saw Deb without Homer. Davis said they were one. She was his inspiration in many ways. I told him that even though he won't be able to see her, he will still be able to feel the impact she had on him.

Jordan said those words helped him start living again.

A picture of Jordan throwing a pass in the Orange Bowl is still on the floor in his den.

Jordan said he needed to put up a lot of stuff. All of my stuff from college is packed up in boxes or a closet, but I'm getting there.

Jordan wore his national championship ring for the longest time, but he lost the crown of the ring while coaching football and was unable to find it.

"I'm not sure if I'll send it off to get it fixed," said Jordan, who was a member of the Hall of Fame.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime deal to get it. I'm a little nervous.

After a trying first season as the starter, Jordan was rarely nervous during his playing days. He was the primary starter at quarterback for the next three seasons after winning the starting quarterback job during preseason camp. He beat out Andy Headen, who played six seasons in the NFL with the New York Giants, and was an athlete.

Jordan and the team had a rough 1980 season. The Tigers lost four of their last six games and Jordan became hardened to the boos.

He said that the most blatant case of racism he faced was when a white man told him that he didn't believe in the ability of a black quarterback to win a football game.

Jordan's response was typical of the way he went about his business on the field no matter how tense the situation became. He was not flustered.

Jordan doesn't know if he was a fan of the school. I didn't face a lot of that kind of thing. I knew it was there and people were talking about it. I didn't worry about it because I knew my coaches and teammates were behind me.

I said to you that you can't stop me because I don't face you. The quarterbacks are booed. It's just part of playing the position. I wondered if it was different with me because I was black. It's probably so. Sometimes I was booed. Those boos turned to cheers.

Georgia couldn't promise that Homer Jordan would be given a chance at quarterback, but Danny Ford was willing to give him one.

Jordan was indebted to his coach for sticking with him no matter what the outside world said.

It's a relationship that has lasted. Whenever Jordan returns to the school, he always looks for his old coach.

"I know where he parks for games, and he still gives me a hard time every time I see him," said Jordan, adding that it's usually something crazy.

Just how crazy?

Jordan said that most of it can't be repeated. He knows how I feel about him. In the beginning, he probably believed in me more than he did. He was nice to me. I can say that. He wanted me to be me.

Ford, who still lives on his farm just outside of Clemson in Pendleton, remembers Jordan's calming presence, his penchant for delivering in key moments and the way he grew as a leader.

Ford still loves to remind Jordan of his bad start to the 1981 season. The season opener was a close one as Wofford took a 2-0 lead. The fans were restless from the way the 1980 season ended.

Ford said that the first play they called against the Terriers was a bootleg pass, and that the ball bounced into his stomach. "I said, 'Dang, Homer, this isn't basketball.' You don't have to dribble the ball.

The one that became a blip was the 45-10) win by the Tigers. Jordan directed his team to the school's first national title, as well as earning first-team All-ACC honors.

The 13-3 win over Georgia and Herschel Walker was one of the sweetest victories for Jordan, as the unranked Tigers won three games over top 10 teams on their way to the championship.

Jordan, who had to do a lot of checking off and making quick throws against the Dawgs, was responsible for the game's only touchdown when he hit Perry Tuttle in the end zone on an 8-yard pass. It was Jordan's only win as a starter over the Dawgs in a fierce rivalry that was played annually in those days.

Smith said that it was back when you won with defense and kicking. We didn't throw a lot, but Homer was able to throw it. I don't know how Georgia allowed him to leave Athens. It's good for us that they did.

After the win over Georgia, the team needed Jordan to play in a variety of roles, and he adapted to that. The 10-8 victory over North Carolina was the first meeting between a top 10 team in the league's history.

"Defense won it for us that day, and it's the hardest-hitting game I've ever played in," Jordan said.

Jordan threw three touchdown passes in the first half and finished with 270 passing yards to lead the team to a 21-7 victory over Maryland and a spot in the conference championship game.

In that game, I threw 29 passes. Jordan's ability to run and pass made him an ideal fit for the Tigers' offense. We were running the option. The spread is what they call it now, but we didn't throw much. I might have thrown it 10 or 12 times.

Even if it was just for one timely third-down completion from the pocket or a keeper on the option to sustain a drive, Jordan was there.

Austin said that the better he was, the tighter the situation was. Homer was quick, but not fast. If he got up on you, you could forget about tackling him. You should let him get past you and then try to run him down.

The 1981 national championship team was honored at Memorial Stadium. The program has won two more titles.

Ford loved Jordan as a football player, but he wouldn't be lying if he said he thought Jordan could be their starting quarterback.

Ford said that they never promised him he would be their quarterback. We promised him that he would have a chance to win the quarterback job.

Ford believed that he was getting a kid who knew the meaning of perseverance. Jordan's father died of diabetes and his mother worked two jobs to keep the family afloat.

"It wasn't always easy on Homer, from losing his wife to going through what he did to be the first black quarterback in school history, it was even harder for him because we were coming off an average season," Ford said. Homer never complained. He never complained when he was playing. He didn't complain after.

I can't think of a negative thing to say about Homer Jordan.

The 1981 team gathered earlier this season for their reunion. Ford said it was a special time.

As he hugged players, greeted their families and re-lived that historic season from 40 years ago, his mind kept going back to the image of an exhausted Jordan slumped in front of his locker at the old Orange Bowl with an IV tube strapped to him.

Jordan's scramble on third-and-23 was the key to the win.

Ford said that he made two or three of their players miss and barely made the first down. "After the game, everybody was in there yelling and jumping up and down, and Homer was over there taking an IV because he's given out." Everything was left on the field by him.

And left a legacy that will live on.