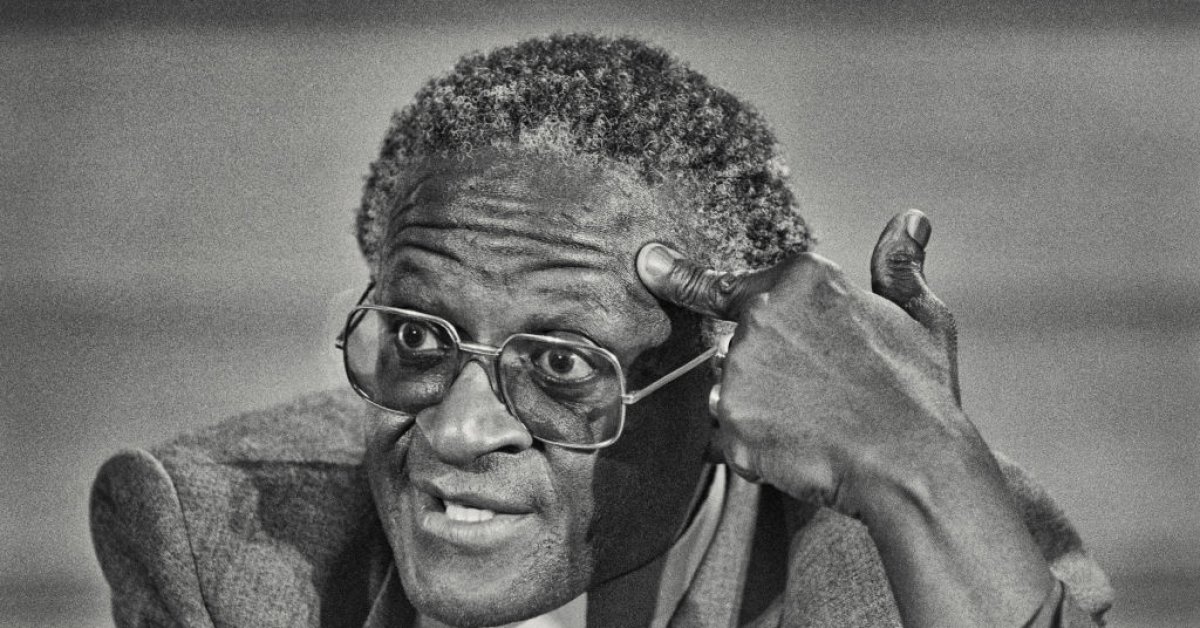

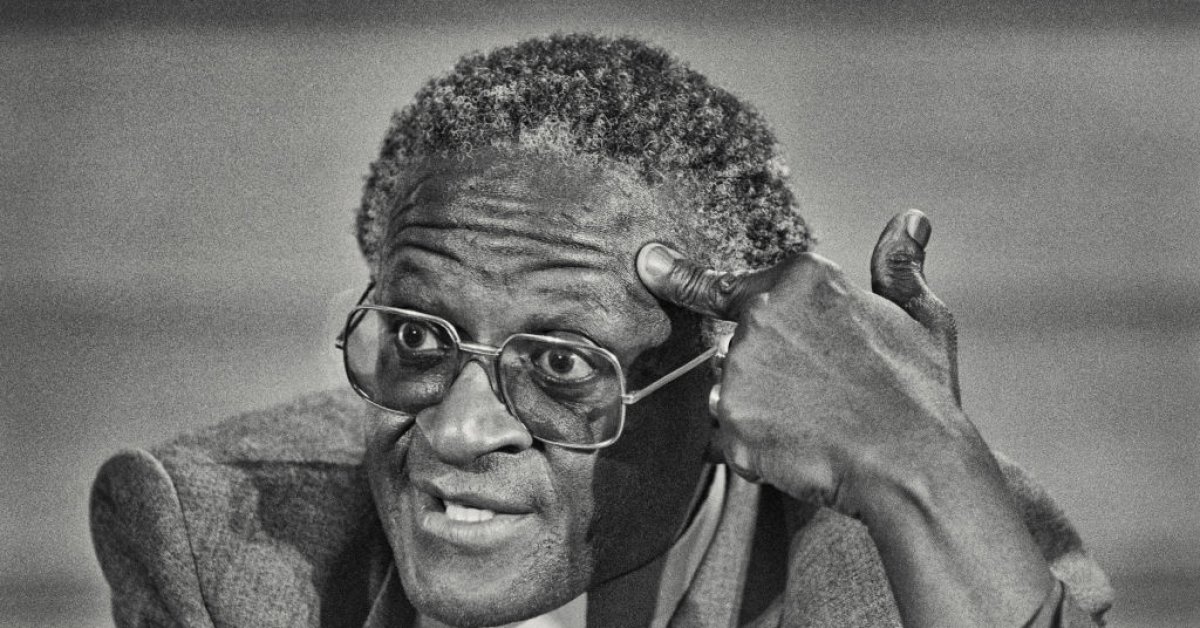

South African anti-apartheid campaigner, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and Archbishop Emeritus, and one of the world's most revered religious leaders, died in Cape Town on Sunday at age 90, bringing to an end an extraordinary life filled with courage, love and a passion for justice.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said that the death of Tutu marks another chapter in the nation's farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have left a liberated South Africa. F.W. de Klerk, the last white South African president, died in November.

He was a man of great integrity and strength against the forces of apartheid, and he was also tender and vulnerable in his compassion for those who had suffered oppression, injustice and violence.

In 1997 Tutu was diagnosed with prostrate cancer and had been hospitalized a number of times.

The leader of the Anglican Church in South Africa, and an icon of peaceful resistance to injustice, is best remembered for his courage in the fight against apartheid. He used his religion as a platform to advocate for equality and freedom for all South Africans regardless of race. The apartheid system was corrosive to the spiritual, physical and political development of the white population it was supposed to protect. He was quoted as saying that whites were dehumanized by being oppressors.

He used the Christian principles of love and forgiveness as a weapon in his fight to dismantle apartheid, and he prayed for his opponents. He was uncompromising when it came to his moral philosophy. You are either in favor of good or bad. You are either on the side of the oppressor or on the side of the oppressor. He wrote a statement to the Congress in 1984 saying that he couldn't be neutral. He said that if an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.

According to the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu, there is a secret to joy.

After the end of apartheid, it was a philosophy that continued to fuel his activism. When full democracy came to South Africa in 1994, Tutu used his stature and boundless energy to advocate for social justice and equality, taking on issues of HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, climate change and the right of the dying to die with dignity. He became a peace advocate and pushed for an end to conflict in Israel-Palestine, as well as in other countries. He risked conflict with his own church by campaigning against the United States' illegal imprisonment of suspected terrorists in Cuba and became an outspoken supporter of the rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer community. He said in 2006 that it was a matter of justice. It is a matter of justice to discriminate against women. It is a matter of justice to oppose discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Even though he was confronted with some of the most egregious aspects of human behavior at home and in his travels, he never lost his faith in his fellow man. He once said that human beings are made for goodness despite all of the ghastliness.

His sermons went beyond the homily of the day to encompass the news of the world. He wove jokes, observations and passion into his speeches, deftly conducting his audiences into a state of uproar over injustice. He directed the heightened emotions towards constructive action. His authorized biography was published in 2006 and it said that he was a ruffian for peace. The voice of the voiceless will always be the voice of the voiceless, because of the strident, tender, never afraid and humorless voice of Desmond Tutu.

The son of a school headmaster and a domestic servant, he became a teacher like his father. He quit when the South African government started to impose policies that restricted employment opportunities for black South Africans. In 1959 he attended a theological college, and in 1960 he became a priest in the Anglican church. He left South Africa to continue his studies in London, where he experienced a life of freedom from apartheid. He noted in his biography that he was sure there was racism there. We were protected by the church. It was wonderful. We didn't have to carry our passes anymore and we didn't have to look around to see if we could use that exit. It was a huge relief.

In 1975, he became the Anglican Bishop of the country of Lesotho. He was elected the first black secretary general of the South African Council of Churches two years later. His position in the church allowed him to advocate for an end to apartheid while also giving him protection from the South African authorities. With most of the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement jailed or in exile, Tutu became the movement's defacto head and a leading spokesman for the rights of Black South Africans. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his efforts to draw attention to the discrimination of the South. The awards committee said it was meant to support him and the South African Council of Churches, as well as all individuals and groups in South Africa who care about human dignity, Fraternity and democracy.

He became the first black man to preside over a million-strong congregation in Cape Town two years later. Right-wing white Christians protested outside the cathedral, calling it the death of the Anglican church. The church's official residence was located in an area reserved for white residents only, so the apartheid government asked him to apply for the status of "honorary white" so that he could reside on the premises. He said no.

The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was catapulted into a global cause by the receipt of the peace prize by Tutu. The country's government was brought to its knees by nearly a decade of eloquent advocacy by Tutu and his supporters around the world. Nelson Mandela was elected the first black president of South Africa in 1994 after the end of the apartheid system. The new president was introduced to the nation by Tutu. He has described that moment as one of the best in his life. I told God if I die now, I don't mind.

He was appointed as head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was tasked with investigating human rights abuses committed by both sides during apartheid. The two and a half-year-long proceeding was presided over by Tutu, who sometimes collapsed into anguished tears after hearing details of some of the worst atrocities.

There are questions for Desmond Tutu.

Often called the moral conscience of South Africa, Tutu was also known to be a bit of a scold. He made enemies of the African National Congress for his criticisms of their failures, and held all of the nation's leaders to the highest standards. He criticized President Thabo Mbeki for his denial of the country's HIV/AIDS epidemic, and criticized President Jacob Zuma for his moral failures. Zimbabwe's former president, Robert Mugabe, once described Tutu as an "evil little bishop" for his sermons against the Zimbabwean dictator's kleptocratic rule.

In 2007, Tutu criticized religious conservatives in the clergy for their attitudes against homosexuality. He said that the Church had failed to demonstrate that God is welcome. He wouldn't worship that God if it was gay. He told his supporters in Cape Town that he wouldn't go to a gay heaven. I would rather go to another place.

As a founding member of the Elders, an organization of former world leaders who work together to promote human rights and world peace, Tutu continued on his quest to put an end to injustice until he decided to retire from public life in 2010. He said at the time that he had spent too much time at airports and hotels because he was not growing old gracefully at home with his family. The time has come for me to slow down, to sip tea with my beloved wife in the afternoons, to watch cricket, to travel to visit my children and grandchildren, rather than to conferences and conventions and university campuses.

He emerged from his seclusion when he needed to. He wrote a letter to his friend and fellow winner of the prize, asking her to speak up for the rights of the Muslim minority in the country. He posted a letter on social media in which he said that he was now elderly, decrepit and officially retired, but that he was breaking his vow to remain silent on public affairs. The price of your ascension to the highest office in the country is too steep if you don't speak about it.

The world has never seen a more articulate voice for justice than that of Nomalizo Tutu, the wife of the man known as the "Father of the Nation".

In a speech in support of assisted death, the archbishop said he hoped to have a peaceful and joyful funeral for himself. He said that he would like to be cremated, even though it made some people uncomfortable, and that he would like to have his ashes interred at St. George's Cathedral in Cape Town. He wanted a simple coffin, one that would serve as an example to others of the importance of frugal funerals.

He wanted his death to be seen as the end of his extraordinary life, not as an occasion for sadness. He said that dying is part of life. We have to die. The millions of people that came before us cannot sustain the Earth. We have to let those who are not yet born go.

Contact us at letters@time.com if you have any questions.

There is an update post.