Patrick Murphy, a soldier in the Union Army who was court-martialed for desertion, was pardoned by Abraham Lincoln.

It's rare to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. Each day from December 25 through January 5, we'll post a story about one that fell through the cracks. The forensic analysis of Lincoln's letter shows that the April 14, 1865 date was forged and can't be removed without damaging the document.

The document containing Lincoln's pardon of a Civil War soldier has been the subject of much controversy since it was discovered in 1998. A new analysis by scientists at the National Archives has confirmed that the date was forged, although the pardon is genuine. The authors concluded that it was not possible to restore the document to its original state without causing more damage.

Thomas Lowry is a retired psychiatrist and amateur historian, specializing in military records of the Civil War. In 1998, he and his wife Beverly were combing through a lot of rarely studied courts martial at the National Archives. Archive staffers trusted the Lowrys because there were no security cameras in the room. The couple found a lot of documents with Lincoln's signature.

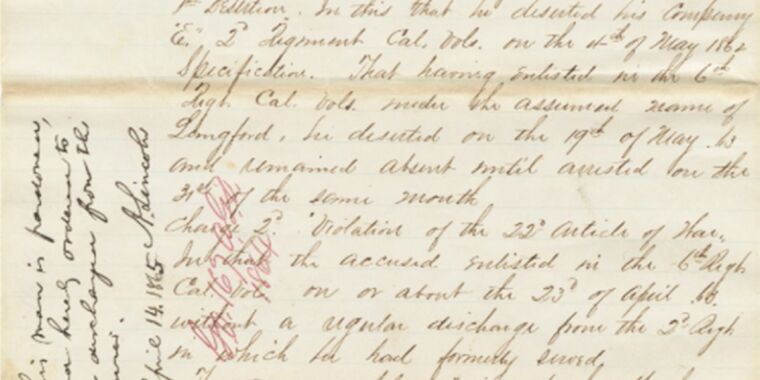

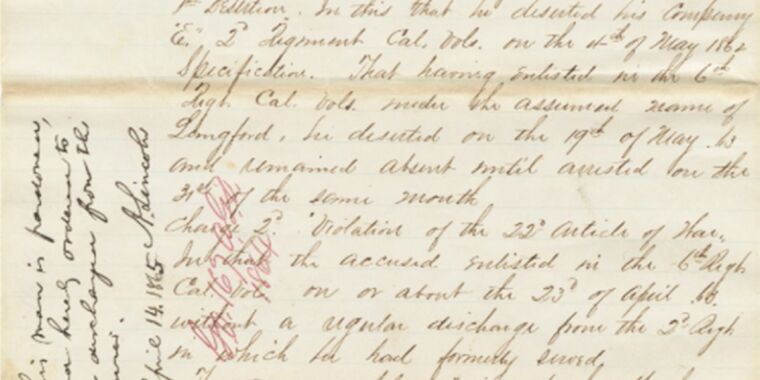

Patrick Murphy, a private in the Union Army who had been sentenced to death for desertion, was pardoned. The pardon is written in the left margin of a letter dated September 1, 1863. The man was pardoned and ordered to be discharged from the service. It was signed by Lincoln.

The document was significant because it was on April 14, 1865, the day Lincoln was killed at Ford's Theater in Washington, DC. The president's last act was one of mercy, and the pardon was seen as proof of that.

In the January 2011 Inside the Vaults video, there is a discussion of altering an original Lincoln document.

The Murphy pardon was displayed in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom. The ink on the "5" in "1865" was noticeably darker than the ink on the "8". It seemed as if there was another number underneath it. Lincoln's writings from the 1950s were consulted by Plante. The pardon was issued in April of 1864, a full year before Lincoln was killed. The document had been altered to make it more significant.

Advertisement

The man who made the discovery was turned to by investigators. They began talking to Lowry in 2010. The investigators knocked on the historian's door one January morning after he stopped communicating with the Office of the Inspector General.

The National Archives released a statement saying that Lowry had admitted to altering the date on the pardon. The fountain pen and ink were brought into the research room, along with the "4" in "1865" being changed to a "5." The statute of limitations for tampering with government property had run out, but he was barred from the National Archives for life.

Close up of altered date and "A. Lincoln" signature.

But there's a twist, as he re-canted, claiming that he had signed the confession under duress. He said the investigators assured him that it wouldn't be publicized and he wouldn't suffer any consequences. He told the Washington Post that he considered the records sacred. It's out of character for me. I'm a man of honor. His wife thought a former Archives staffer was the culprit. The agency denied the allegation.

Conservators at the National Archives were interested in studying the altered document more closely and to see if the original date could be restored by removing the forged "5." Plante told the Washington Post that Lowry purposely used ink that would last a long time. The ink was consistent with the period.

The National Archives has a cutting-edge heritage science laboratory with expertise in a broad range of analytical techniques that have become popular in cultural forensics circles. In the case of Lincoln's pardon, the team looked at the date and signature under visible and ultraviolet light, as well as using XRF analysis to compare the composition of the ink.

The ink used to write the "5" was different in color compared to the other numbers in the date, according to an examination of the "1854" under magnification and reflective fiber optic lighting. The authors wrote that the ink from a scratched away number can be seen below and beside the darker '5' as well as smeared across the paper.

Advertisement

The ink used by Lincoln in the "L" of his signature, the questionable "5," and the remnants of the abraded "4," are all analyzed to compare.

The paper under and around the "5" was found to be thinner than the rest of the document.

The team looked at the verso of the document and found that the front text was visible on the back of the sheet.

The National Archives used XRF analysis to identify elements in the ink. The ink used in Lincoln's signature and the "8" in the date was expected to have some sulfur and potassium in it. They found calcium in the paper.

They compared the ink used to write the "5" to the ink used to write it and found that the signals for iron, potassium, and sulfur were much higher for the latter. The "5" ink has a thicker application. The iron to sulfur and iron to potassium ratios are not the same.

This analysis confirmed Plante's pessimism about removing the forged "5" and restoring the pardon to its original state. The authors wrote that removing the new '5' would damage the original materials of the historical document.

There is a book on forensic science international. The About DOIs is in the 10.1016/j.fsisyn.