Grant Tremblay was sitting at his computer at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, listening in on a meeting when he saw a bunch of emails in his inbox. The email title was "Cycle 1 JWST Notification Letter."

He knew it was Blacker Friday when he and his colleagues in the astronomy community were waiting.

Blacker Friday was not related to discounts or Fridays. It was a Tuesday. It was the day that Tremblay, an astronomer at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, would learn if he would be given a small amount of time to use the James Webb Space Telescope, one of the most powerful space telescopes ever created.

We wanted to answer fundamental questions that can't be answered any other way.

Blacker Friday is named after the co-runs of the science policies group at the Space Telescope Science Institute. The institute is responsible for selecting which astronomer gets to use the Hubble Space Telescope. Each year, Blacker would send out a flurry of emails to hopeful astronomer, all on the same day, to inform them if their proposals to use the telescope had been accepted or rejected. Blacker Friday was born.

For the first time ever, astronomer were told if they would get time with the new space observatory, which is more powerful than Hubble, on Blacker Friday. The nearly $10 billion NASA-built telescope is set to launch to deep space at the end of December and will allow it to peer into the Universe like never before. The observatory's first year of life is known as Cycle 1 and the task of figuring out which proposals should get time with the telescope was daunting. When the most advanced piece of space equipment first turns on, how should it be prioritized?

The science needs to be revolutionary.

Klaus Pontoppidan, an astronomer and project scientist at the JWST, tells The Verge that science that is transformational is the most interesting. We don't want the observatory to do things better than they have done before. We wanted to answer the fundamental questions that can't be answered any other way.

The power of JWST.

The day before Christmas, NASA plans to launch the JWST. The launch is a real holiday for the astronomy community. One of the most anticipated space science missions of the 21st century is the JWST, which has the ability to change astronomy and astrophysics.

The telescope is the closest thing to a time machine. With a 21-foot wide mirror, the JWST will be able to see in theIR with incredible sensitivity. It will be able to see objects that are 10 to 100 times fainter than the Hubble Space Telescope can see, and it will be able to see things in 10 times better detail. It will gather light from stars and galaxies that are up to 13.6 billion light-years away. The universe is thought to be about 13 billion years old, and the galaxies that will be observed formed around 100 to 250 million years after that. Our Universe was in its infancy then, and we will be getting baby photos from the JWST.

Nearly every area of astronomy will be addressed.

The telescope will help us understand the structure of the Universe, and perhaps tell us if it will go on expanding forever. It will be able to peer into the centers of the galaxies and find supermassive black holes. The births and deaths of stars will be observed. It will look back at our own Solar System to see the faintest objects at the edge of our neighborhood. It will be able to see the edges of distant worlds. Christine Chen, an associate astronomer at the STScI, tells The Verge that nearly every area of astronomy will be addressed.

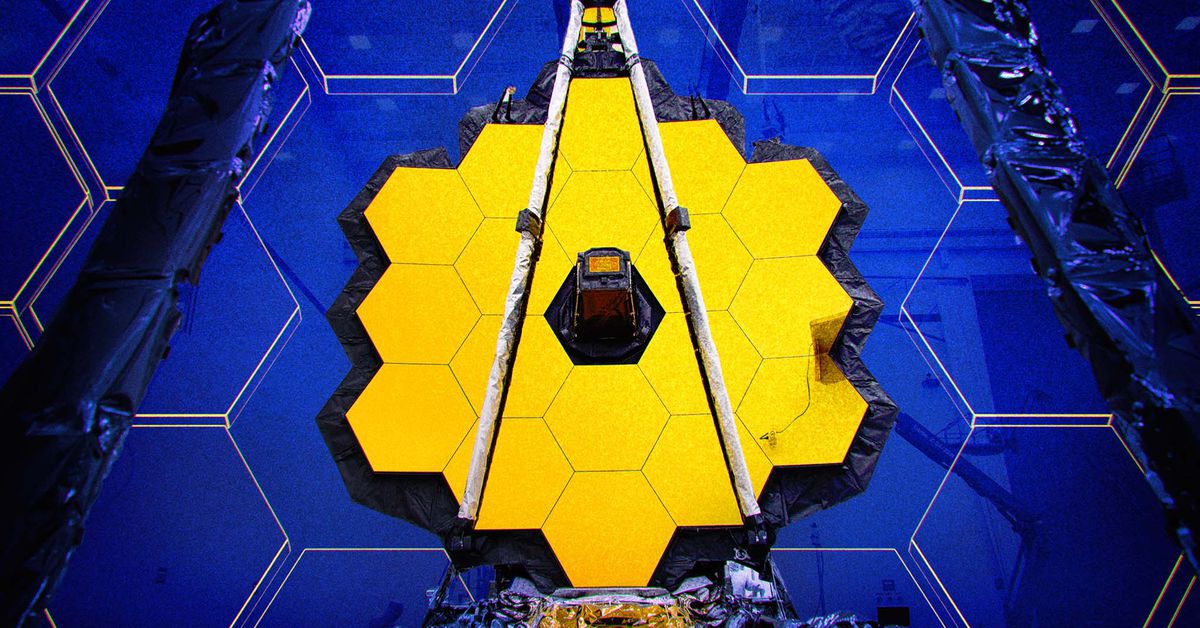

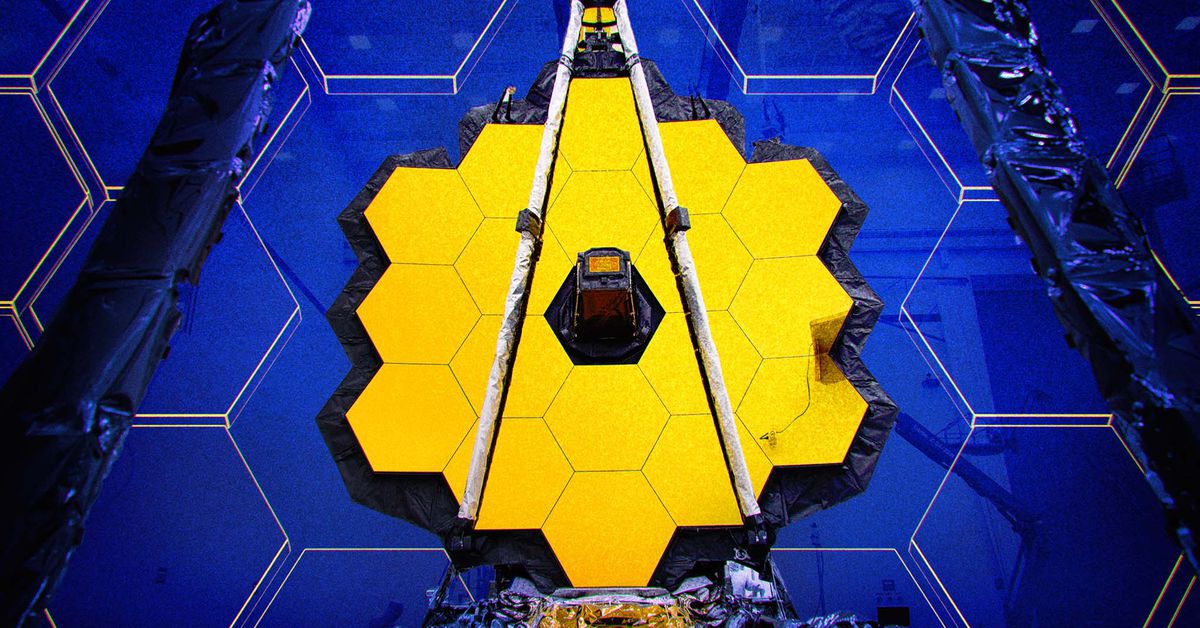

Noupscale is a file on thechorusasset.com.

An artistic rendering of JWST was completely unfurled.

The image is from NASA.

The promise of JWST has always been unfulfilled. The road to the launchpad has been paved with cost overruns and technical issues since the first iteration of the telescope was conceived in 1989. Between 2007 and 2011, NASA had a goal of spending between $1 billion and $3.5 billion. The total cost ballooned to $9.7 billion after one target launch date was missed.

The world of astronomy grew as everyone waited for the telescope. Since the 1990s, a new field has emerged that focuses on the study of planets outside our Solar System. We have discovered thousands of worlds around alien stars since the first detection of an exoplanet in 1992. The discovery of an alien solar system consisting of seven planets roughly the size of Earth shocked the world. Three of the seven planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system are thought to be in the star's habitable zone, where temperatures are thought to be just right so that water can pool on a planet's surface.

After discovering so many planets, the astronomer want to find a planet that is the size of our world and is in the right place at the right time to form liquid water. Traditional methods for detecting exoplanets are not very effective because they are so faint. The light that passes through the atmosphere of some alien worlds may be able to be used to determine what chemicals are present. Maybe it could detect signs of life.

The transformational leaps in observational astronomy are enabled by making larger pieces of glass.

When the telescope was first designed, it was not thought of as an exciting area of science, but now it is. There are more people who are very eager to get just a few hours with the most advanced space telescope.

All of the transformational leaps in observational astronomy are enabled by making larger pieces of glass. When you make a piece of glass that is large enough, and especially when you launch it into space, the discovery space for that observatory grows with time. It does not diminish.

The science is being chosen.

The Space Telescope Science Institute is in charge of determining what JWST does in space. Pontoppidan says that they are similar to the software part of the observatory, where NASA is the hardware part.

There were a few false starts along the way, as the schedule for the first year of the project was not figured out until after a long time. Astronomers were told to submit their proposals by March of next year, when the telescope would be ready to launch. The telescope wouldn't launch until 2020 at the earliest, just a week before the deadline, according to NASA. The launch date was not determined until after the deadline.

The COVID-19 Pandemic caused another postponement in March 2020. Astronomers proposed their ideas by November 24th, 2020, two days before Thanksgiving. There were more than 1,000 ideas that had been submitted.

The process could not be handled alone bySTScI. Astronomers and astrophysicists from around the world are members of the Time Allocation Committee. They were separated into 18 panels, each one consisting of about 10 people tasked with looking over proposals for different areas of space science and ranking them based on three important criteria: how much the proposal will impact knowledge within a subfield, how much it will advance astronomy in general, and whether the The Institute didn't want to give time to an observation that could be done with any of the other telescopes currently online because of how many people want to use JWST.

We regret to inform you.

The committee got to work evaluating all of the proposals. The process was dual anonymous to try to eliminate bias. The people writing the proposals had no idea who would be evaluating them, and the people on the committee had no idea who they were analyzing. 30 percent of the winning proposals are helmed by women, and scientists studying for their PhDs saw more success in getting their ideas approved. Since nobody knows who wrote the proposal, students can be just as successful as their mentors.

:noupscale,cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorusasset/file/23114554/cosmoswebbcomparisionwithcosmos hubbleacs.

The area of sky that will be covered by COSMOS-Webb is larger than the area that was surveyed by the full Moon and Hubble.

Jeyhan Kartaltepe (RIT); Caitlin Casey (UT Austin); and Anton Koekemoer (STScI) are graphic designers.

The proposals the committee found to be the most significant were selected. Each proposal was given a number of hours of observation time. Scientists from 41 countries around the globe submitted 266 proposals for the project.

The Harvard astronomer submitted nine proposals for the first year. Nine new emails were in his inbox. The emails come from the Science Mission Office. He quickly clicked through them and read them again.

Dear Dr. Tremblay, I am writing to you.

We regret to inform you.

He read the phrase nine times.

It was a disappointment but not a surprise. Tremblay told The Verge that he wasn't broken up by not getting time this year. I knew it would be very competitive. It is okay. We will resubmit.

The astronomer at the University of Texas was having a different kind of Blacker Friday. She was at home with her baby in her lap while she scrolled her phone. She saw the email in her inbox.

I would like to send a letter to Dr.Casey.

We are happy to inform you.

The project she had proposed, called Cosmos Webb, had just been approved. The Institute was giving the most time to fulfill her project to the person who submitted the most proposals. A patch of sky the size of three full Moons will be the focus of the project. The young universe will be created like the Hubble Deep Field, which showcased some of the earliest galaxies we could observe at the time. The team will be using the enhanced capability of the JWST to image older galaxies. If the Hubble Deep Field were printed on a sheet of paper, it would look like a 16-foot by 16-foot mural on the side of a building.

All I had to say was, "We got it."

Staying silent so as not to wake her sleeping child,Casey jubilantly log into Slack and messaged her colleague on the project, Jeyhan Kartaltepe, an astronomer at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

"All I had to say was, 'We got it,'" says the man. She was also dumbfounded. For the rest of the day, both of us could not focus. It was a flurry of joy and excitement.

Noupscale is a file onchorusasset.com.

The planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system could be depicted in an artistic way.

The image is from NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The seven-planet TRAPPIST-1 system will be getting a lot of attention during the first year of the JWST, with up to seven different programs dedicated to studying this strange cluster of worlds. We will be looking in the atmospheres of these planets and dozens more to see if they are suitable for life. There are hundreds of targets that will be observed by the JWST.

The committee tried to be as logical as possible with their final decisions, but everyone agrees that it's possible that serendipity comes into play. There were a lot of programs similar to ours that were also up for consideration. There is always a chance of luck in the final selection process. Maybe someone on the panel liked the way we presented information.

The first year.

For the first year of life, different groups are given 10,000 hours of observing time. More than 4,000 hours were set aside for scientists who helped design and build the instruments for the telescope. There are about 460 hours of discretionary time that the STScI has. The data from these hours will be made public immediately so that anyone who didn't get time with the telescope can analyze the observations and write their own studies.

10,000 hours is more than the number of hours in a year. The time to account for any mistakes was overprescribed bySTScI. The observatory will point at its intended targets autonomously during the two-week period when it is scheduled by theSTScI. From time to time, it is possible that the JWST will fail to execute some commands. If that happens, the next observation will be done by JWST. The Institute wants to make sure the telescope has a plan in case of an error. We don't want to run out of observations at the end of the year.

Noupscale is a file on thechorusasset.com.

The James Webb Space Telescope was on top of a rocket.

The image is from the ESA/M.Pedoussaut.

Time will be carved out for targets we don't know about. These are events like the destruction of a star, known as a supernova, or the merger of two dense stars, known as a kilonova. If an eruptive event occurs in the sky, the operators of the telescope are prepared to change the schedule so that they can observe it.

By the time of the year, the priority of the observations will be determined. NASA knows what the telescope will do, but won't tell. It is supposed to be a surprise.

The proposals that have been approved will occur, even though flexibility is going to be key for the first cycle. If a target is missed, there is a second chance to see it six months later. If a target is not observed in the first year, it will bleed over into next year. Everything that gets through the committee will execute on the telescope as long as it works, Chen says.

If everything goes well with the telescope's launch, NASA plans to conduct at least five and a half years of science with it, and hopefully up to 10 years. The observatory's lifetime is dictated by its limited fuel reserves, which are needed to help reorient JWST in space. The mission will end when fuel runs out.

The community has a lot of demand for the telescope. I think it is a great thing.

It's quite a ways off. The first thing that must happen is for the JWST to survive its trip through space. Once it reaches its final home 1 million miles from Earth, scientists will have six months to test the instruments on board before the real science begins.

After a period of transformational science has passed, it will be time to submit another round of proposals. Tremblay will be involved with one proposal for Cycle 1 as a collaborating partner, but he will submit his ideas again for Cycle 2. If it doesn't get accepted, he will understand.

As an astronomer, I could wallpaper my hallway with rejections that I have received. The community has a lot of demand for the telescope. I think it is a great thing.