The structure of our galaxy is difficult to reconstruct from Earth's vantage point.

It's really hard to gauge the distance to something in space when you don't know its brightness. There are a lot of objects that are not known to us. Sometimes, we can miss huge structures that we think should be under our noses.

There is a new set of enormous structures at the outer regions of the Milky Way disk. Astronomers will be trying to solve the mystery by conducting follow-up surveys.

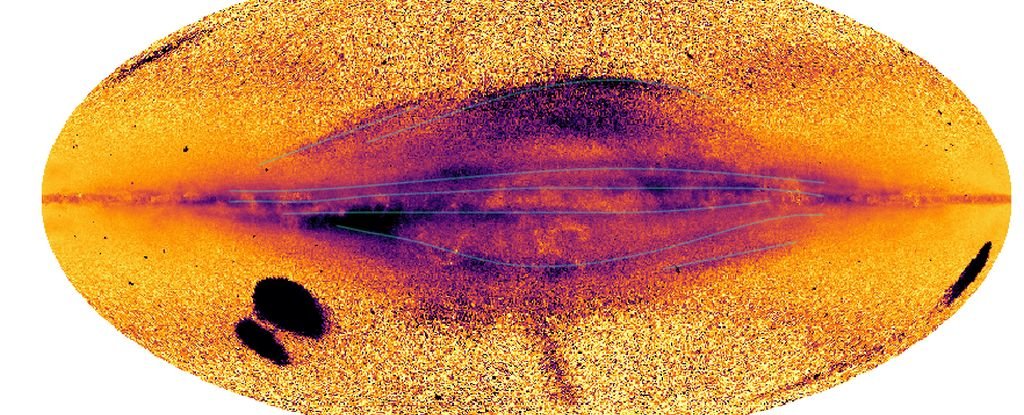

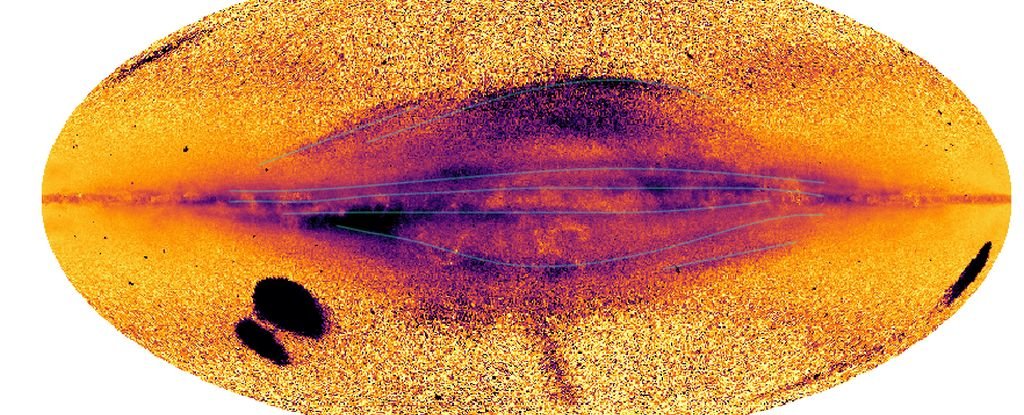

Thanks to the European Space Agency's Gaia space observatory, the discovery came about.

The Sun-Earth L2 Lagrangian point is a pocket of space created by the interactions between the two bodies.

It carefully studies stars in the Milky Way over an extended period, watching to see how the positions of stars seem to change against more distant stars. The distances to the stars can be calculated using this.

The atmospheric effects can interfere with the measurement. From its position in space, Gaia has an advantage. The data from the space telescope has revealed a number of structures and stellar associations we had no idea about.

The new structures were identified by a team led by astronomer Chervin Laporte of the University of Barcelona in Spain. The data showed previously known structures with more clarity than we had seen before.

The researchers wrote in their paper that they had found multiple previously undetected new filaments in the outer disk.

Some of these structures are believed to be excited outer disk material, kicked up by satellite impacts and currently undergoing phase-mixing. The structures can stay coherent in configuration space for several billion years due to the long timescale in the outer disk regions.

The spinning filaments are not new. Simulations show that the interactions between the Milky Way and its satellite galaxies could produce structures. There are a lot of satellites in the sky.

We need another explanation because the sheer number of the filaments found by Laporte and his colleagues vastly surpasses those seen in such simulations.

The remnants of tidal spiral arms that were excited at various times by interactions with satellites could be one of the possibilities.

There is a chance that they are the crests of the distortions of the Milky Way disk that occurred due to collision with other galaxies. It's not an unreasonable supposition that the Milky Way has a history of colliding with other galaxies.

The researchers believe that such crashes could cause ripples on a pond.

The next step is to try and determine which of the scenarios is the most likely.

The intervening dust obscures most of the galactic midplane, which is why this region of the Milky Way has remained poorly explored.

The motion of a star is unaffected by dust. The data from the Gaia motions helped us uncover these structures. The challenge remains to figure out what these things are, how they came to be, why in such large numbers, and what they can tell us about the Milky Way.

The research has been published in a journal.