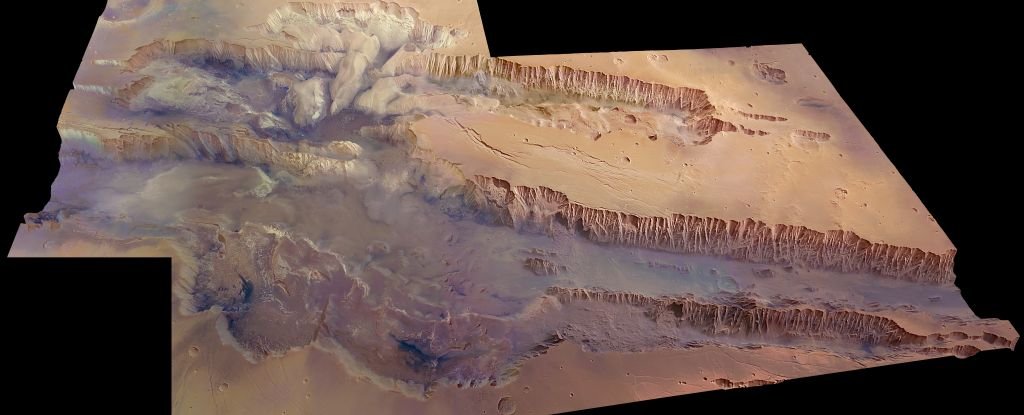

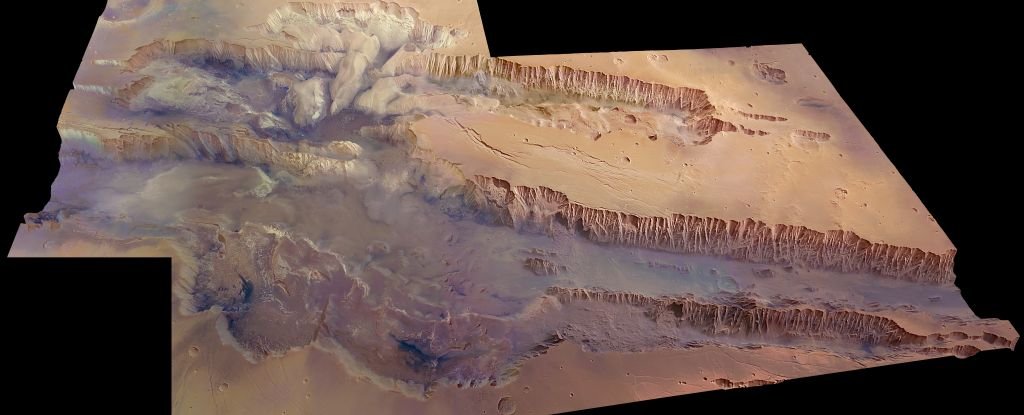

There is a system of canyons that scars the face of Mars.

The Grand Canyon of Mars is a 4,000 kilometer (2,485 mile) canyon with a high quantity of hydrogen. The new data from the FREND instrument shows this.

The soil in the region is rich in water at depths up to three feet below the surface, which could be a new way of finding precious stuff on the extremely arid world.

"With the Trace Gas Orbiter, we can look down to one meter below this dusty layer and see what's really going on below Mars's surface, and locate water-rich 'oases' that couldn't be detected with previous instruments," said physicist Igor Mit.

The area with a large amount of hydrogen was found in the huge Valles Marineris canyon system, which is thought to have as much as 40% of the near-surface material being water.

There is water on Mars. At the cold poles, it is bound up as ice. At the equator, it's too warm for water ice to form at the surface.

It's possible that water can be found under the surface, but previous searches only found it at higher latitudes.

The Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector is what it is. Rather than looking at the surface of the red planet, FREND looks at the inside. The researchers said this allows it to see the hydrogen content of Mars's soil up to a meter below the surface. It seems to have done, in the observations taken between May and February.

"Neutrons are produced when highly energetic particles known as galactic Cosmic rays strike Mars, and so we can deduce how much water is in a soil by looking at the neutrons it emits," said physicist Alexey Malakhov, also of the Space.

We found a central part of the area filled with water, far more water than we expected. This is similar to Earth's permafrost regions, where water ice is permanently under dry soil because of the constant low temperatures.

A mosaic shows a man on the face of Mars. The NASA.

The high-hydrogen region is about the size of the Netherlands, and overlaps with Candor Chasma, one of the largest canyons in the Valles Marineris system. The researchers think that the substance is likely water ice below the surface, because minerals on Mars typically don't have much water.

There is a mystery as to how that water could persist. The pressure and temperature of the Mars equator should prevent the formation of water reserves. There may be a combination of conditions that allow it, such as patchy isolated deposits that have been there for some time, or the angle and orientation of steep slopes.

It will take further investigation to confirm what form the water on Mars takes, not just the conditions that allow for it. It is possible that stores of water in a permafrost-like form may have preserved frozen fragments of life, just as we have found here on Earth.

There are exciting possibilities for Mars exploration as a result of the discovery. Water that might be found not far beneath the surface of Mars would be an amazing asset for exploration and for keeping water-reliant humans alive.

It makes scientists even more interested in visiting the largest canyon in our Solar System, the Valles Marineris.

Colin Wilson of the European Space Agency said that the result shows the success of the programme.

Knowing more about how and where water exists on Mars is essential to understand what happened to the once-abundant water, and helps our search for habitable environments, possible signs of past life, and organic materials from Mars's earliest days.

The team's research has been published.