NASA's next- generation asteroid impact monitoring system has just been activated and has made it easier for us to sleep.

The new system can take data from telescopes and work out the path of an asteroid over the next century. The updated system is very good at predicting special and unusual cases that are not covered by the original system.

If an asteroid strike is likely, we could get a lot of warning about it. The advanced alert setup is more sophisticated than ever, because of the uncertainty involved in the predictions.

The first version of Sentry was in operation for almost 20 years, and was led by an automation engineer with Starlink.

It was based on very smart mathematics. You could get the impact probability for a newly discovered asteroid in under an hour.

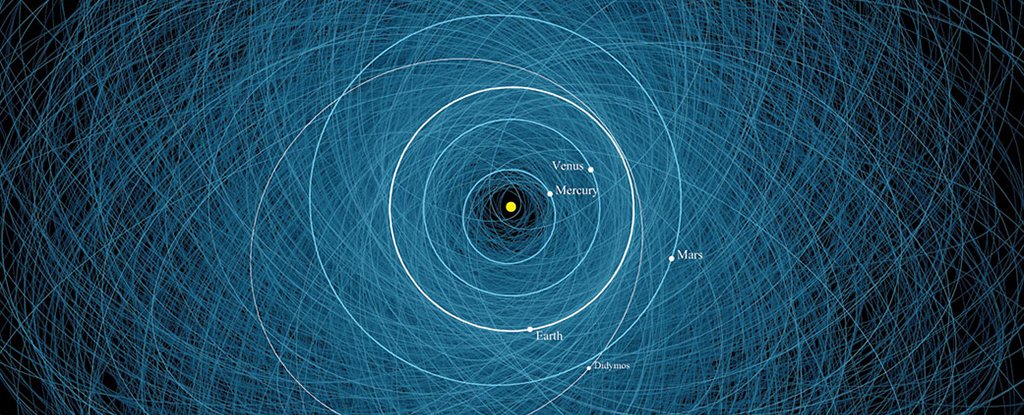

Astronomers get to work on figuring out the most likely path of a new near-Earth asteroid when it's detected because of the effects of other objects in the Solar System. These are calculated cleverly and can be relied upon, but can't include every single small influence.

The Yarkovsky effect is a small force that can make a big difference over time.

There were lots of manual calculations needed to make predictions when the asteroids Apophis and Bennu came up. This important detail is included in the calculations of Sentry II.

The programs determine the likelihood of a chance encounter with our planet. One thing is crossing paths while another is not.

The original Sentry would look at evenly spacing points along the region of uncertainty and then analyze each one in more depth based on certain trajectory assumptions, whereas the new Sentry uses thousands of random points along the region of uncertainty, without any assumptions about which are more likely to be hit than others.

The astrophysics is complex, but it means that Sentry-II has less of a bias about which points in the potential asteroid's path should be taken into account. The researchers think it's similar to looking for a needle in a haystack.

"In terms of numbers, the special cases we'd find were a very tiny fraction of all the NEAs that we'd calculate impact probabilities for," says Roa Vicens.

We need to be prepared because we are going to discover many more of these special cases when the Vera C. Rubin Observatory goes online.

Even without the new and more powerful space observation equipment mentioned by Vicens, we're already detecting around 3000 NEAs every year, with a running total of over 30,000. A lot of asteroids are trying to be tracked.

A better method for tracking asteroids that pass very close to Earth is one of the improvements in the new system. Our planet's gravity can cause a lot of uncertainty when it comes to asteroid trajectory, but Sentry-II is better set up to factor in this.

If we were to collide with an asteroid, we would have to decide if we would hit it or not, but with the look-out, we should know.

"Sentry-II is a fantastic advancement in finding tiny impact probabilities for a huge range of scenarios," says senior research scientist and astronomer Steve Chesley from JPL.

It pays to find the smallest impact risk hidden in the data when the consequences of a future asteroid impact are so large.

A study about the capabilities of Sentry- II has been published. Here you can see the data collected by the two companies.