The World Health Organization named a new coronaviruses variant "Omicron" and designated it as a "variant of concern."

Why are scientists worried about this variant of the disease? There's a lot we don't know about the variant.

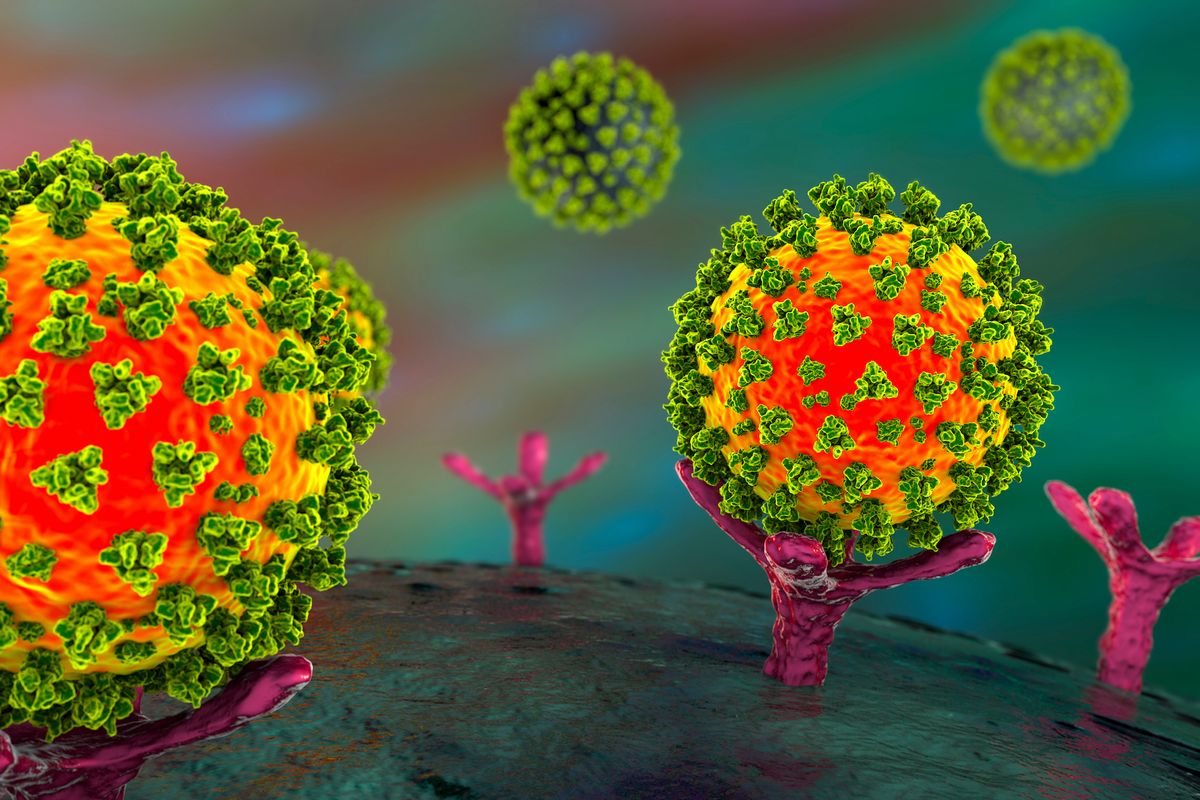

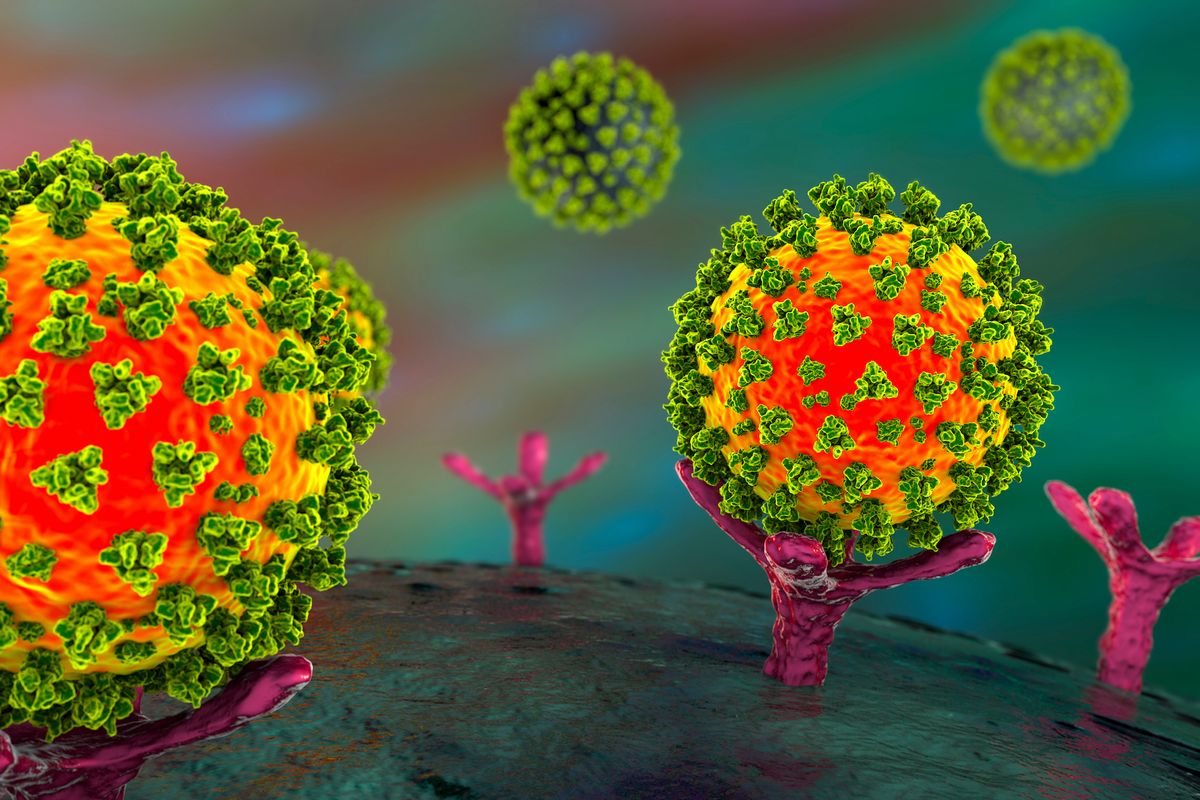

Scientists are concerned that Omicron has a lot of genes that code for the spike protein, which the coronaviruses use to invade human cells. According to a statement from the WHO, people who recovered from COVID-19 may have a higher risk of reinfection with Omicron.

Here's how the SARS-CoV-2 mutants stack up.

There are some good videos for you.

It's not clear how severe Omicron is or how current COVID-19 vaccines will fare against it. The vaccines are likely to be less effective due to these changes, but they will still give some protection. Here's everything we know about Omicron.

Omicron was reported to the WHO by officials in South Africa after a large increase in cases in the previous weeks. The first known case of Omicron in South Africa was from a sample taken in November.

South Africa was the first to report Omicron to the WHO, but it's not clear what country the variant emerged from. Many countries have banned travel to South Africa. The director of the Yale Institute of Global Health told NPR that there was little utility in banning things. Omicron has been found in Canada, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, Scotland, Botswana, Israel, Australia and Hong Kong, according to The Washington Post.

The Omicron variant can be easily detected by a common test that targets one of the three genes. The WHO says that this variant has been detected at faster rates than before.

There are changes in the genes.

Omicron has more than 30 genes that have been altered. According to The Guardian, 10 of these are in thereceptor binding domain.

The WHO has released a technical brief that says that some of the past variants of the virus are "concerning" and that they could be linked to higher transmissibility.

The likelihood of further spread of Omicron is high according to the brief.

It is the severity that matters.

It's not known if Omicron causes more severe disease.

According to the WHO, there is evidence that the rate of hospitalizations in South Africa is increasing, but this may be due to increasing overall numbers of people becoming infections. According to Our World in Data, only a small percentage of South Africa's population is fully protected against COVID-19.

The first infections in South Africa were in university students. According to the Telegraph, only a small percentage of the population of South Africa is older than 65. It's not clear if the variant will cause more severe disease in people who are at increased risk.

There is no evidence that symptoms of Omicron are different from previous ones.

Dr. Coetzee said that the patients she's seen so far with the new variant have had mild symptoms.

Coetzee told the Telegraph that most of the patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were healthy young men who were tired. None of her patients needed to be hospitalized or had lost taste or smell.

It's too early to say if Omicron causes milder or more severe disease than earlier versions.

Transmissibility is possible.

It's not clear if Omicron can spread from person to person.

The number of people in South Africa who have been testing positive for COVID-19 has increased in areas battling Omicron, but it's not yet clear if the increase can be explained by the spread of the new variant or other factors.

The vaccine is effective.

It's not known how effective the current COVID-19 vaccines will be.

Most COVID-19 vaccines are used in the U.S. to prime the immune system against the spike protein. Omicron has many different types of spikes and experts are worried that current vaccines may not be as effective at training the immune system to recognize it.

"Based on a lot of work people have done on other variations, we can be pretty confident that these are going to cause a drop in neutralization, or the ability to attach to the viruses and stop them from invading human cells," said Jesse Bloom, an evolutionary biologist.

Experts told The Guardian that vaccines will probably still give some protection against Omicron, even though they may be less effective.

"I think a blunting rather than a complete loss of immunity is the most likely outcome," Paul Morgan, an immunologist at Cardiff University told the Guardian.

Danny Altmann, professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told The Guardian that T cells may be more "impervious" to differences among variant compared with antibodies.

Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are two of the companies working to understand how effective the vaccines are against the variant.

Paul Burton, Moderna's Chief Medical Officer, said on the Andrew Marr Show that a new vaccine will be available in early 2022. Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech's COVID-19 vaccines are based on the same technology as their previous vaccines, which is quicker to develop and edit.

The Moderna platform allows us to move very fast.

Live Science published the original article.