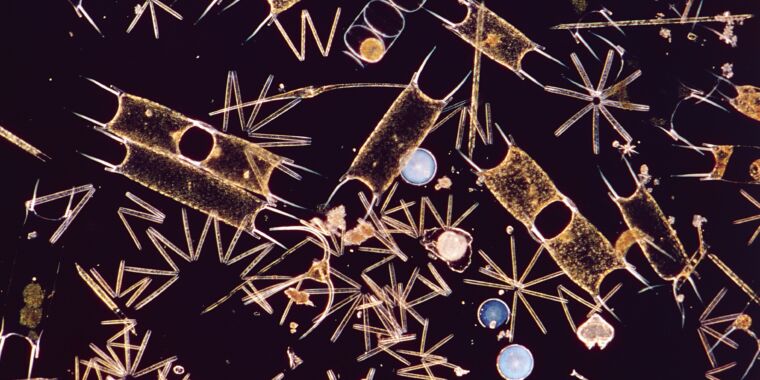

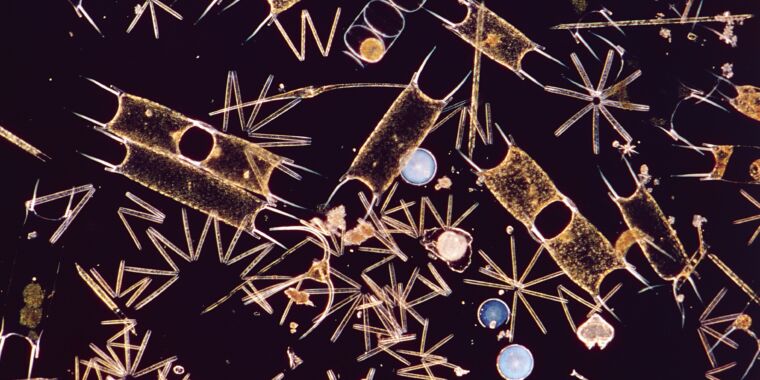

The Microphotograph of Thalassionemataceae, the phytoplankton, isEnlarge

On November 19, 1969 the CCS Hudson went out into the open ocean. The first complete circumnavigation of the Americas was thought to be the last great, unexplored ocean voyage by many of the marine scientists on board. The ship would head north through the Pacific and then through the southernmost point in the Americas, Cape Horn, before returning to the ice-packed Northern Passage.

The Hudson made frequent stops so its scientists could collect samples. One of the scientists boarded the Hudson in Valparaso. A marine ecologist at Canada's Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Sheldon was fascinated by the tiny plankton that seemed to be everywhere in the ocean. To find out, the group hauled buckets of water up to the lab and used a machine to count the plankton they found.

They discovered that the abundance of an organisms is related to its body size in the ocean. The more organisms you find in the ocean, the smaller they are. They are a billion times more abundant than tuna.

Advertisement

It was surprising how this rule seemed to play out. The plankton samples were organized by order of magnitude, and they found that each size had the same mass of creatures. In a bucket of water, one-third of the mass of plankton would be between 1 and 10 micrometers, another third would be between 10 and 100 micrometers, and the final third would be between 100 and 1 millimeter. The number of people in a group dropped by a factor of 10 when they moved up a size group. The total mass was the same as the population size changed.

The rule might govern all life in the ocean, from the smallest bacterium to the largest whales. This hunch was correct. In plankton, fish, and in freshwater, the spectrum has been observed. The same pattern in soil was observed by a Russian zoologist three decades ago, but his discovery went largely unrecognized. Eric Galbraith is a professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of Montreal. Everyone has the same size cells. For a cell, it doesn't matter what body size you are, you just kind of do the same thing.

Humans seem to have broken the law of the ocean. Galbraith and his colleagues show in a paper that the Sheldon spectrum no longer holds true for larger marine creatures. If the Sheldon spectrum were still in effect, the total ocean biomass of larger fish and marine mammals would be higher. Galbraith says that life seems to have been following a pattern for reasons that we don't understand. Over the last 100 years or less, we have changed that.