She was flying home from a holiday in Samoa when she saw a large mass floating on the ocean, hundreds of kilometres off the north coast of New Zealand.

A raft of floating rock was produced in the largest eruption of its kind ever recorded, when a raft of floating rock was produced in the ocean.

"We knew it was a large-scale eruption, comparable to the biggest eruption we've seen on land in the 20th Century," said volcanologist Rebecca Carey from the University of Tasmania, who co-led the first close-up investigation of the historic 2012 eruption.

The floating rock platform it generated was harder to miss than the initial incident, which was unnoticed by scientists.

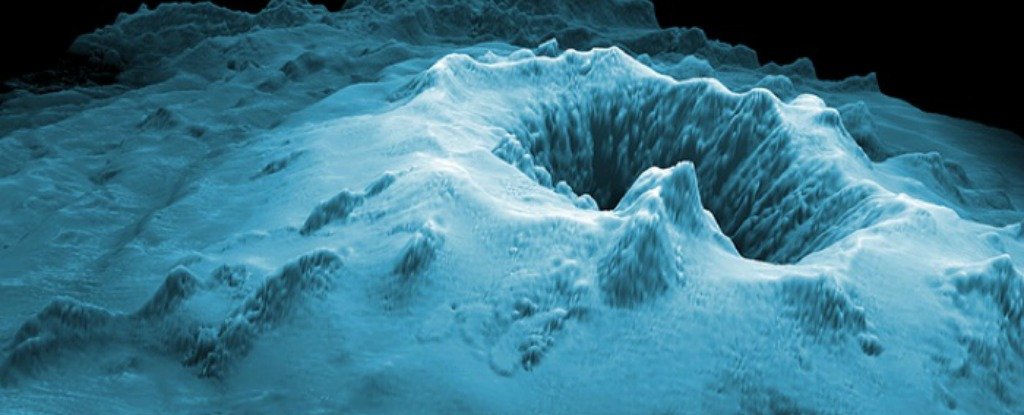

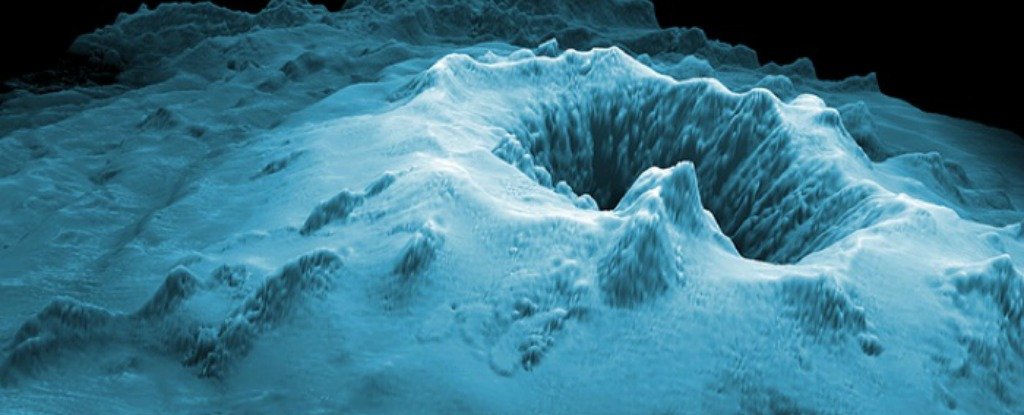

The Havre caldera has high-resolution seafloor topography.

In 2012 the raft covered 400 square kilometres of the south-west Pacific Ocean, but months later satellites recorded it spreading over an area twice the size of New Zealand.

Scientists were taken aback by the enormity of the rocky aftermath when they inspected the site in 2015.

"When we looked at the detailed maps from the AUV, we saw all these bumps on the seafloor and I thought the vehicle's sonar was acting up," said volcanologist Adam Soule from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The bumps were made of a block of pumice, some of them the size of a van. I have never seen anything like it before.

The investigation shows that the eruption of Havre Seamount was more complex than anyone knew.

The caldera, which spans nearly 4.5 kilometres, discharged lava from some 14 vents in a "massive rupture of the volcanic edifice", producing not just pumice rock, but ash, lava domes, and seafloor lava flows.

It may have been buried under an ocean of water, but for a sense of scale, think about 1.5 times larger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

Three-quarters of the material erupted, three-quarters or more floated to the surface, and tons of it washed up on shorelines.

The rest of it was scattered around the nearby seafloor, which brought devastation to the biological communities who called it home.

Carey said that the record of the eruption on the volcano itself was unfaithful.

It is important for how we interpret ancient submarine volcanic successions that are now uplifted and are highly prospective for metals and minerals that a small part of what was actually produced is preserved.

It's a rare opportunity to study what happens when a volcano erupts under the sea, with samples collected by the submersibles yielding what the scientists say could amount to a decade's worth of research.

One of the team, Michael Manga from UC Berkeley, said that underwater eruptions are fundamentally different from land eruptions.

There is no on-land equivalent.

Science Advances reported the findings.

The original article was published in January.