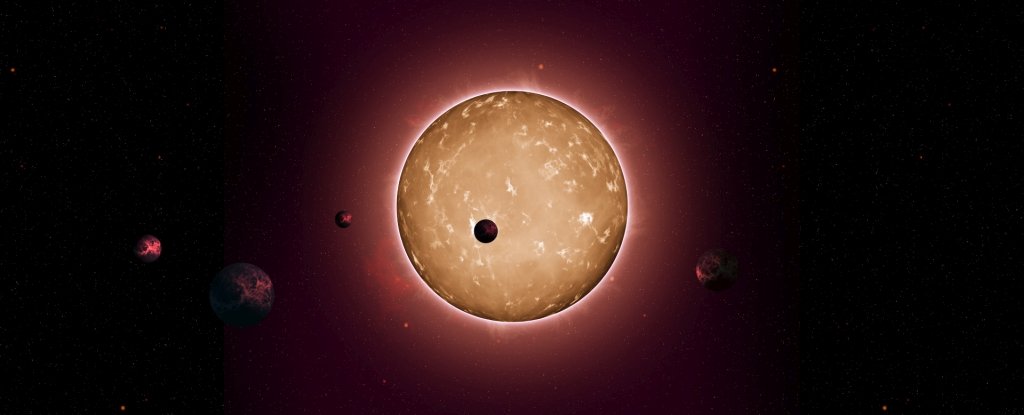

We're trying to bring the total of confirmed exoplanets to 5,000.

A team of scientists have identified hundreds of previously unknown exoplanets in the data from the retired Kepler space telescope.

The development of an algorithm for identifying dips in stellar brightness that indicate the presence of an exoplanet was the key.

"Discovering hundreds of new exoplanets is a significant accomplishment by itself, but what sets this work apart is how it will illuminate features of the exoplanet population as a whole," says astronomer Erik Petigura of the University of California, Los Angeles.

During his time in the sun, the astronomer spent nearly a decade looking at the sky and recording the stars. When an exoplanet passes between us and the star, the aim was to capture faint dips in brightness that occur in the star's light. A series of dips indicates the presence of a body.

The amount of light the exoplanet blocks reveals its size is determined by the length of time between dips.

It all sounds very straightforward, but it takes a long time to identify the signals amidst the noise. Humans perform better at signal detection than software.

Jon Zink is an astronomer at UCLA and he developed an algorithm to help pick up the slack. The 500 terabytes of data from the second mission was fed into the software. The result was 381 exoplanets that had been previously identified, and 366 new exoplanets.

There was a system with two gas giants that were very close to their host star. Planetary scientists look for unusual cases like this because they allow us to understand the parameters of what's possible for planetary systems.

Each new world provides a glimpse into the physics that play a role in planet formation.

Zink and his team were not the only ones working on the data. Over 300 exoplanets have been added to the list of confirmed exoplanets.

When a signal is identified as a potential exoplanet, it is initially filed as a candidate. Astronomers need to rule out all other possibilities in order to confirm that it is an exoplanet. The exoplanets discovered by Zink and his team are in this category.

There are thousands of candidates. The number of confirmed exoplanets was lower as of 18 November.

Valizadegan and colleagues have developed a deep neural network that runs on NASA's Pleiades supercomputer. It can distinguish between false positives and real exoplanets.

Valizadegan said that it was possible to be sure that something was a planet. "ExoMiner is more reliable and accurate than both existing machine and human experts because of the biases that come with human labeling."

He and his team used the data from the archive. These were exoplanets that had already been identified and were awaiting confirmation. 301 of them were confirmed by ExoMiner.

None of these newly confirmed exoplanets are Earth-like, or in the potentially habitable zone of their solar systems, but they are important for understanding planetary system statistics in the Milky Way.

This helps us understand how planetary systems evolve and grow.

Valizadegan said that they can transfer the learning from training ExoMiner to other missions, including TESS, which they are currently working on. There's room to grow.

Each of the two papers has a set of tools that can be used to streamline the process of exoplanet hunting. They offer a way to potentially automate the tedious processes associated with identification and confirmation, freeing up scientists to work on interpretation and analysis of the exoplanets out there.

It's a great week for exoplanet research.

Zink's team's paper has been published in The Astronomical Journal, and Valizadegan's team's paper has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal.