Our primate ancestors were able to walk on two legs sometime between 6-7 million years ago.

This is a feature researchers use to distinguish hominins from other apes. It remains an intriguing mystery.

We became fully bipedal about 2 million years ago, but there were many steps along the way. A new study analyzing the remains of a female Australopithecus has found a new step.

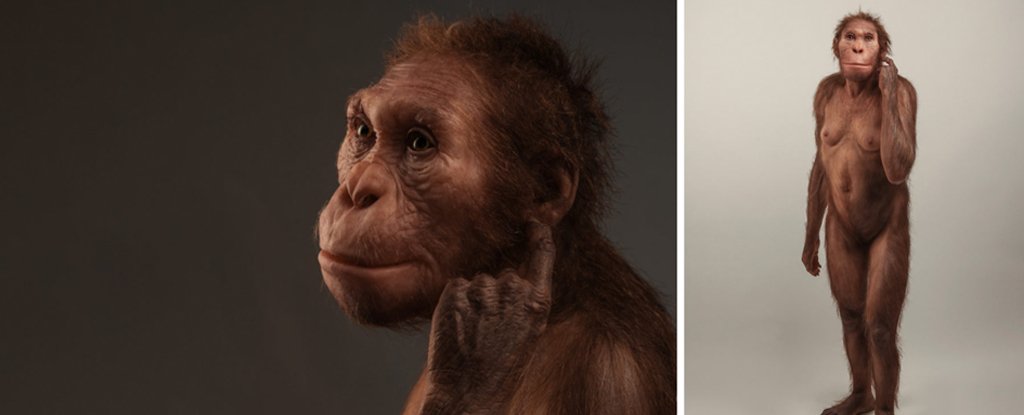

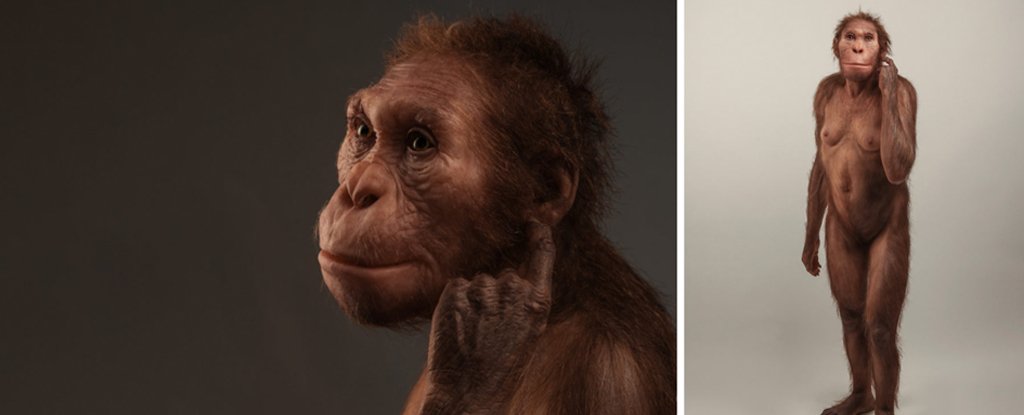

"Issa walked like a human, but could climb like an ape," says Lee Berger from the University of the Witwatersrand.

The Silhouette shows the newly-found vertebrae and other bones from the species. NYU and Wits University.

The primate's skeletal system had to be reorientated to achieve our tall stance.

The lower part of the human spine is curved. The lordosis curve helps us bear the weight of the top part of our body.

The fossils of an adult female Australopithecus sediba were found in South Africa in 2008. It was unclear if she had an ancestral straight or modern curvature of her spine because of the missing pieces.

Scott Williams from New York University says that the hominin fossil record has only three comparable lower spines.

The flexible foot joint and bone structure of her fingers suggest she was well suited to a life in the trees.

The dental analysis shows that the diet was high in fruit and leaves, like that of the apes. She was capable of standing upright because of the angle at which her femur connects to her knee joint.

Two lower spine fossils were found in 2015, they fit with the rest of the remains. Her species had a curved lower spine, which was confirmed by reconstructions using micro-CT scans of the fossils.

The best-preserved hominin lower back ever discovered is made up of these vertebrae.

The bones of the species have been found.

She and her kind are thought to have had an intermediate shape between humans and great apes. They have lordosis, but they also have long costal processes in their spine.

The researchers said that the spine shows that she could walk on two legs and that she could climb using her upper limbs.

A previous analysis on her hands concluded that she showed some features between apes and humans.

A. sediba's position in our family tree is yet to be looked at, were they a dead end or a direct descendant? The researchers think that their findings may help us better understand ourselves.

"Our lower back is prone to injury and pain associated with posture, pregnancy and exercise (or lack thereof)," the team writes in their paper.

Understanding how the lower back evolved may help us to prevent injuries and maintain a healthy back.

Their research was published.