According to new research, the rate of childhood death in prehistoric times was not as bad as we've been led to believe.

Almost 40 percent of prehistoric babies died within the first year of their lives, according to reports. Anthropologists in Australia looked at a decade's worth of UN population data from 97 countries and found evidence that could challenge the popular belief.

The estimate seems to be based on an incorrect assumption that infant mortality rates determine how many humans die in childhood.

If there are a lot of dead babies in a burial sample, then infant mortality must have been high.

Infant mortality has been assumed to be high in the past in the absence of modern healthcare. The number of babies that were born and the number of babies that were dying is what we get from these burial samples, which is contrary to what we've been told.

The researchers suggest that the number of children buried in ancient times seems to be a better indicator of the rate at which babies are being born than the rate at which they are dying.

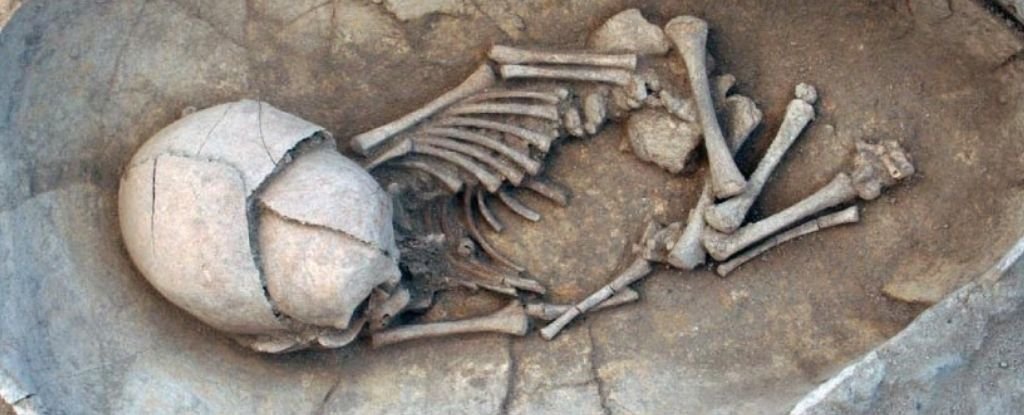

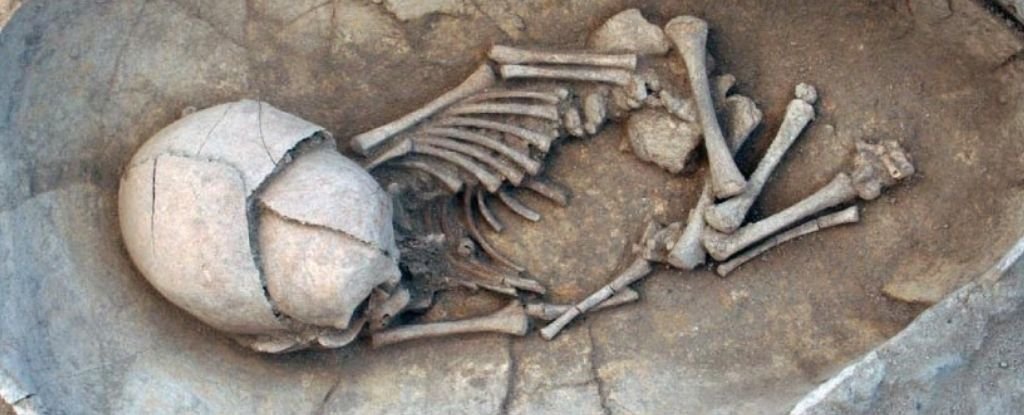

Ancient burial sites are some of the best evidence we have of how humans lived thousands of years ago, but they don't always give us a lot of physical evidence to go on, meaning it's possible to misinterpret what we find.

Even if the rate of death remains stable, more infants will die when a larger number of babies are born.

Researchers have shown that this is true for children born in the past decade.

The death rate for stillborn children, neonates, infants, and children under 5 years of age is predicted by the total fertility rate, although the number of kids being born still doesn't explain all childhood deaths.

Up to 40 percent of the variation seems to be due to unknown factors.

The fertility rate is just one of many factors that can affect one another.

The authors suggest that the ratios tested are not particularly effective proxies for infant and juvenile mortality.

The influence of fertility on infant mortality rates is complex and should not be considered a cause and effect.

The fertility rate was stronger in countries like Japan and Iceland that have low fertility.

In nations with high fertility, like Mali, there was a higher proportion of childhood death than in nations with a higher infant mortality rate.

The lower infant mortality rate in Malian isn't the sole reason for the high rate of childhood deaths.

Researchers say we need to look at ancient baby burials in a more contextual andholistic way. Prehistoric mothers didn't necessarily have to care for their kids because there were so many buried children.

"If mothers were having a lot of babies, then it seems reasonable to suggest they were capable of caring for their young children," says McFadden.

"We forget our ancestors' emotional experience and responses such as the desire to provide care and feelings of grief, which have been around for tens of thousands of years, so adding this emotional and empathizing aspect to the human narrative is really important."

The American Journal of Biological Anthropology published the study.