The first known outbreak of bubonic plague in this part of the world occurred during the 6th and 8th centuriesCE, when the Justinianic Plague spread through west Eurasia.

According to a new analysis of ancient texts and genetic data, its impact was much more severe than previously thought.

Some scholars think that the first epidemic may have killed up to half the population of the Mediterranean region, which may have helped to bring down the Roman Empire.

The consequences of the outbreak might not have had as much impact as the flu does today, according to other historians.

Which leads us to this study. Historians and archeologists need to work together with geneticists and environmental scientists to understand the scale and scope of ancient disease outbreaks, including the arrival of the bubonic plague.

Some historians are hostile to the idea of disease having a major impact on the development of human society, and plague skepticism has had a lot of attention in recent years.

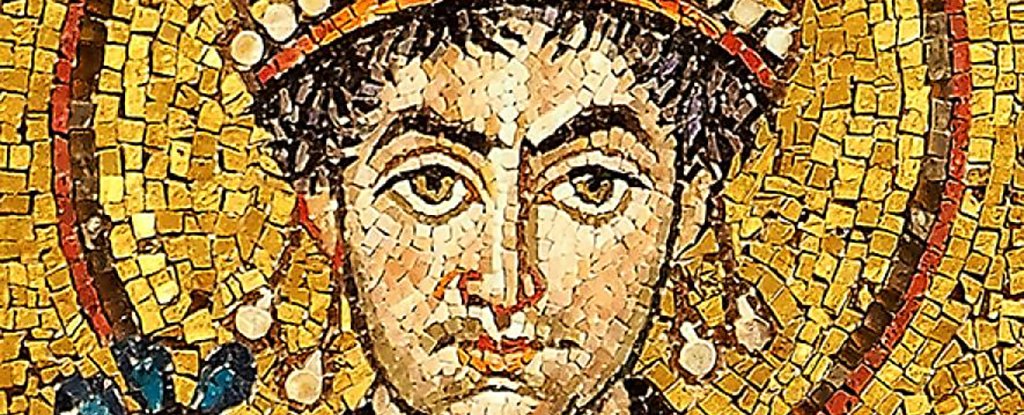

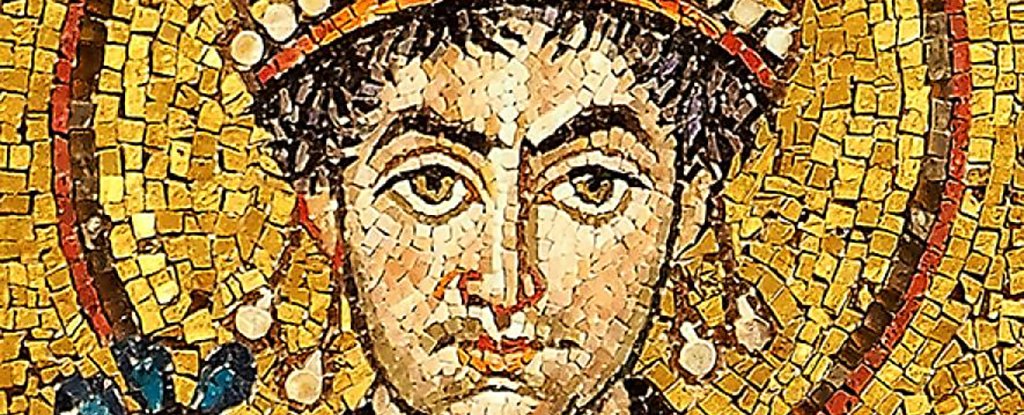

A number of clues show the devastating impact of the Plague, including a flurry of crisis measure legislation passed between the years

The law that was passed to prop up the banking sector of the imperial economy was described as having been written amid the "encircling presence of death" by Justinian. The laws were intended to prevent exploitation of workers during a labor shortage.

The first reduction in the value of gold currency for centuries was represented by a series of lightweight gold coins, which would have been seen as emergency banking legislation at the time. The weight of copper coins in Constantinople was reduced at the same time.

The signs are more significant than other examples. The plague is rarely mentioned in ancient literature, but some studies use it as proof that its effects were not as bad as they could have been.

"Witnessing the plague first-hand compelled the contemporary historian Procopius to break away from his vast military narrative to write a harrowing account of the arrival of the plague in Constantinople that would leave a deep impression on subsequent generations of Byzantine readers."

That is more telling than the number of words he wrote. Different authors write different types of text and their works must be read in a different way.

According to a genetic analysis of a burial site, the bubonic plague spread all the way to Edix Hill in England during this time.

It is more reliable to use a DNA analysis method than it is to leaf through ancient texts. It can show new routes that the disease took around Europe.

The disease may have arrived in England before it hit the Mediterranean, giving historians a fresh understanding of how this first epidemic evolved.

"We have a lot to learn from how our forebears responded to epidemic disease, and how the spread of wealth and modes of thought was impacted on social structures," says Sarris.

Increasing genetic evidence will lead in directions we can't yet anticipate, and historians need to be able to respond positively and imaginatively, rather than with a defensive shrug.

The research was published in the past and present.