A simple online experiment has provided some of the most robust evidence to date that the sound of words can affect language.

There is an argument that suggests at least some words emerged on more universal grounds, despite the fact that linguists generally think of the origin of many commonly spoken words as influenced by a range of local cultural factors. Sometimes a sound looks like the thing it describes.

Since the 1920s, psychologists have wondered how far this relationship might reach using made-up words like 'bouba' and 'kiki'.

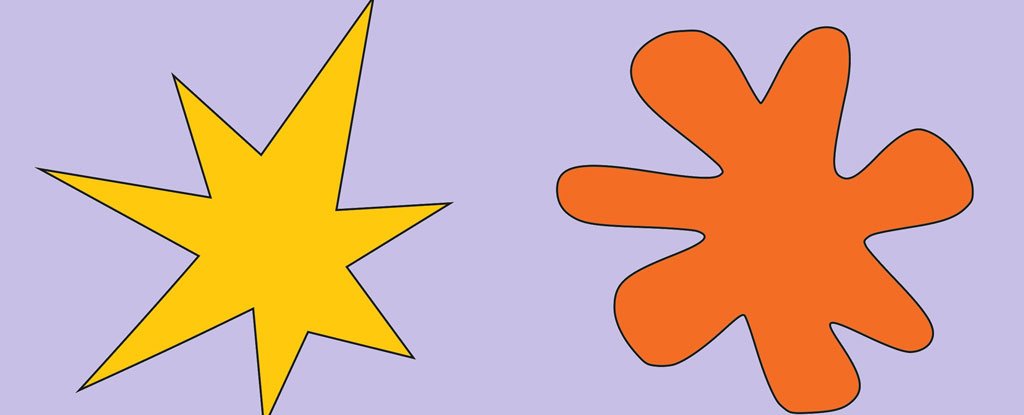

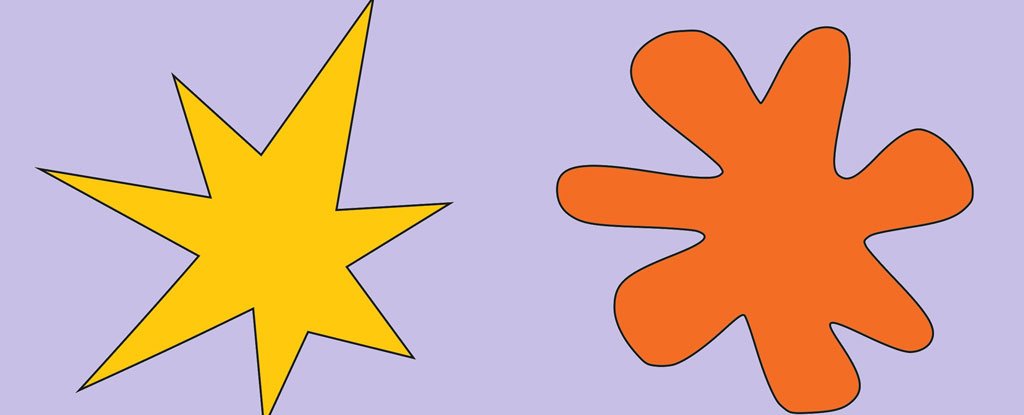

When English speakers are asked to think of a shape, they overwhelmingly think of round, curvy shapes. The word 'kiki' evokes a spikier and less rounded shape.

The findings suggest that there is something about certain sounds that correspond to certain shapes in our brains, and this may have helped form some of the words we speak today. We're not entirely clear on what causes it, despite decades of research.

One possibility is that the letters used to write the words have an influence on the curvature of the words. A group of researchers from around the world have joined together to find out what kind of influence spelling has on people.

The so-called 'bouba/kiki' effect was tested on 917 speakers of 25 languages. Over 70% of these participants associated 'bouba' with a blob-like shape and 'kiki' with a sharp-edged shape.

The association was still present at 63 percent, despite the fact that Japanese and Georgia don't use the Roman alphabet.

The "bouba/kiki effect." The University of Birmingham.

The results challenge a hundred years of conventional wisdom, which suggests that human words are arbitrary and have no clues about what they describe. The only exceptions are onomatopoeias.

The consistent nature of the bouba/kiki effect suggests intuitive mappings in our brains connect aspects of the voice to specific visual properties. Some researchers think that this could have made it harder for humans to come up with new words for their languages.

Studies on toddlers show that we still associate rounded andangular objects with the words 'bouba' and 'kiki' even when we are young.

bouba elicited more congruent responses than kiki, according to the authors.

The effect was only marginally more likely for people who spoke languages with Roman script, and the effect was no stronger for people who used rounder forms for bouba and spikier forms for kiki.

The linguistic pattern remained significant across cultures despite a few individual exceptions.

The authors think the words bouba or kiki might have sounded like other words in those languages.

The word bub means 'wound' in Romanian, which might have made speakers think of sharp, cutting shapes.

You might be wondering why the meanings of words like kiki and bouba matter. These sorts of experiments can reveal a lot about the evolution of human language.

Linguists have been arguing over whether or not there is a universal language system inherent to humans for hundreds of years, and the idea that there may be a natural process for word-formation has largely fallen out of favor in the past century.

John L. Locke's idea that there are no natural connections between a word's form and its meaning has been questioned in recent years.

Other languages like Japanese, Korean, Southeast Asian languages, and indigenous languages from South America and Australia rely more on sound-symbolic words, because they don't allow you to infer meaning from sound.

This type of sound symbolism is called 'iconicity', and it could be a more pervasive property of human language than previously thought.

The authors say that if bouba/kiki were only observed for specific language groups, it could not have played a role in the origins of spoken language.

bouba/kiki becomes more relevant for theories of language evolution by demonstrating that a correspondence between vocal signals and visual shapes is widely recognized regardless of writing systems.

The findings suggest that the sound of words may convey information about size, touch, or color.

Humans could have understood one another and communicated on a more complex level if there was a well-established language.

There will need to be more experiments on the bouba/kiki effect given how contentious the field of human linguistics can be. The findings suggest that the human brain has the same shapes when we hear the same words.

The study was published in a journal.