Critical clues on how undifferentiated cells become specialized ones of which we are made have been provided by an unprecedented glimpse of the human embryo at an early stage of development.

Stem cells can become any part of the body, from brain matter to bone tissue, as an embryo begins to form.

Human stem cells begin to take on these roles in the third week after fertilization.

The process has been mostly a black box.

Stem cells can only be grown in a lab for two weeks. It is not possible to observe gastrulation during pregnancy.

The data from the new findings is provided in Nature.

It was hailed as a "landmark" and a "Rosetta Stone" by experts not involved in the study.

The degree of similarity to the process in humans was always in doubt, despite the fact that samples from mice and non-human primate were used to better understand gastrulation.

The data presented on Wednesday shows how useful experiments on other mammals will be in the future.

Human cells contain all of a person's genetic material, but gastrulation marks the initial stage when certain genes get switched on.

It is the first step in determining if a cell will become part of our blood or brain.

The author of the study described the process as "beautiful" in an online press conference.

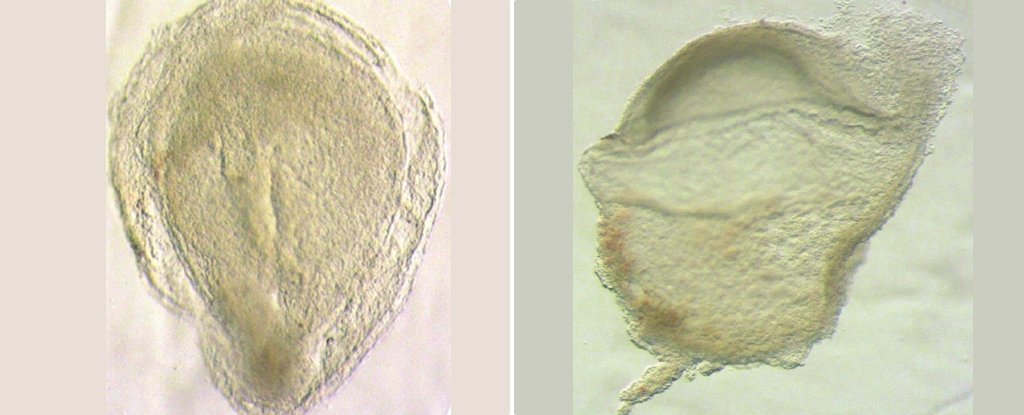

The cells that make up an embryo begin clustering.

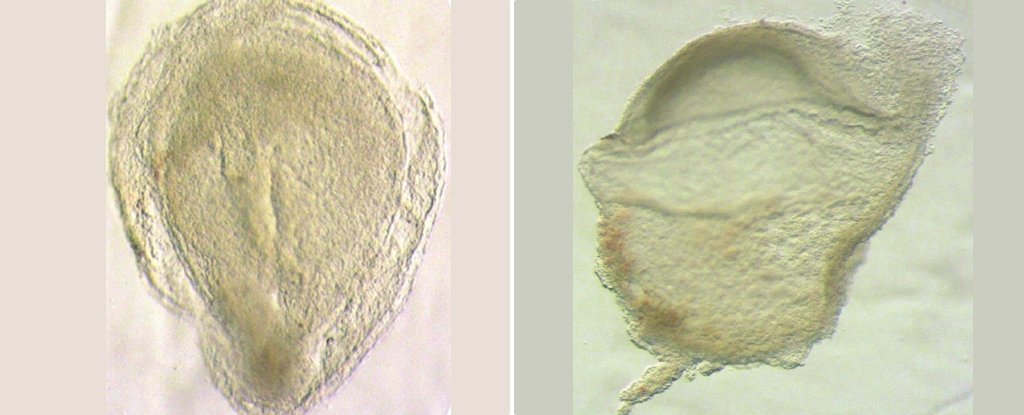

The team used a process called single-cell RNA Sequencing to determine which genes were active in each of the more than 1,000 individual cells after they had analyzed the sample of a donated human embryo.

The map shows where the cells were located in the embryo and which roles they were activated for.

Researchers found more similarities than differences when they compared the findings with mouse embryo observations.

A mouse is a good model of a human.

The presence of blood cells in humans was much earlier than in mice.

There was no material present in the human sample that was similar to the material found in the mice embryo.

The 14-day limit on culturing embryos for study was set to completely rule out study on an embryo with even the beginnings of a nervous system.

A rare sample.

The sample was from the Human Developmental Biology Resource in the UK and was noted by both scientists involved with the study and outside observers.

Most people wouldn't even know they were pregnant after 16 days, but this person did and donated a sample.

The lab spent five years on a waiting list, and that a rules change in how terminated embryos are collected would probably mean a much longer wait in the future.

The sample was a good representation of normal human development and was the subject of a team of tests.

It would be ideal to have more samples to compare, and a change in rules may be necessary to allow that to happen.

"It is a landmark paper, upon which many will base their future findings," said geneticist,Darren Griffin of the University of Kent.

Stem cell biologist Harry Leitch of the Imperial College London said it was an "invaluable resource" that would facilitate further advances in stem cell biology and regenerative medicine.

Agence France-Presse.