Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and affects 44 million people worldwide.

In some nations, the numbers could triple in the next fifty years, and scientists are desperately trying to find ways to protect aging populations.

The method for immunizing mice against AD has been shown to work.

The results look promising compared to other attempts, but we don't know if the approach can be used to vaccine humans against the disease. The authors want to take the research further.

Mark Carr, a drug researcher from the University ofLeicester in the UK, says that if the results were to be replicated in human clinical trials, it could be "transformative".

It opens up the possibility to treat Alzheimer's once symptoms are detected, and also to potentially vaccine against the disease before symptoms appear.

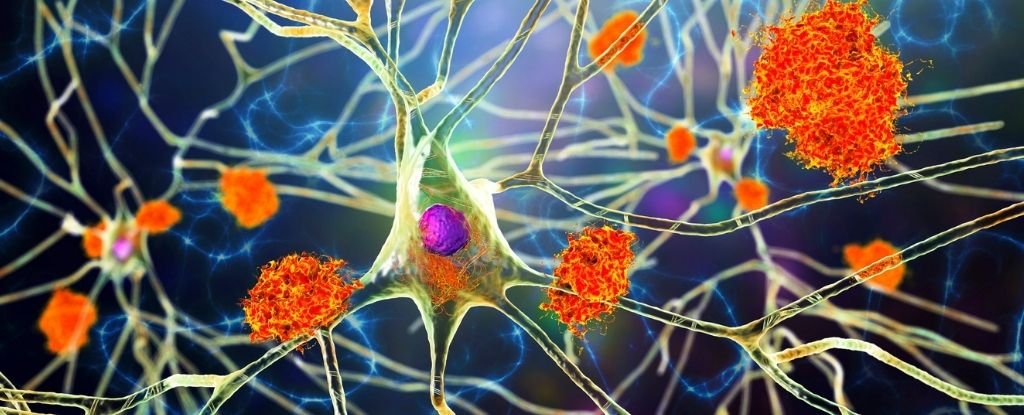

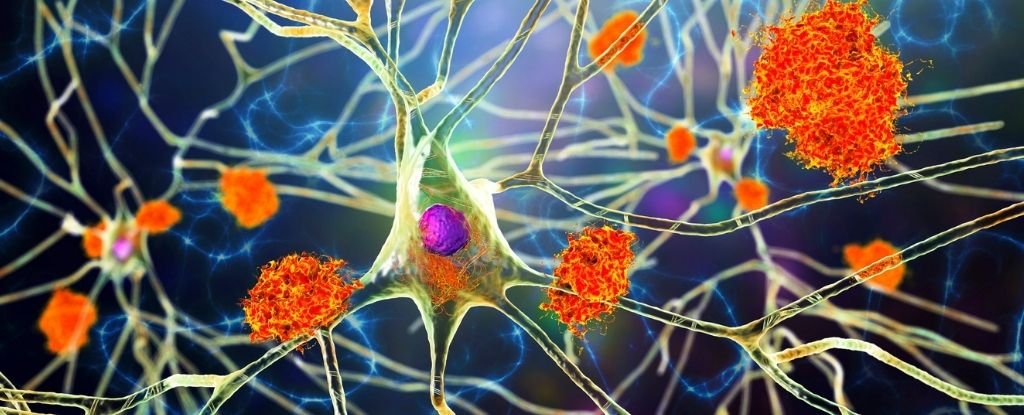

Two-thirds of clinically diagnosed patients post-mortem have plaques of the amyloid alpha proteins in their brains.

When truncated forms of the AmyloidBetaProtein appear, research suggests they can grow toxic and lead to neurodegeneration.

Other AD treatments that target amyloid alpha have been shown to have adverse impacts, but this new approach only targets the toxic truncated amyloid alpha.

The researchers found a family of antibodies that could leave healthy full-length ones alone.

The authors created a version of the antibody for our own species to make sure it works for humans.

The team used X-ray crystallography to peer closer at the action of the antibody in the brain of a humanized mouse.

The result reduced plaque load in the mouse brain, and it also helped with memory deficits and neuron loss.

Researchers created a more direct 'vaccine' by engineering a similar hairpin-shaped protein. The vaccine triggered the mouse immune system to produce its own type of antibodies.

The results of the vaccine on its own were similar to those of the antibodies.

The vaccine may not be able to prevent all forms of Alzheimer's, even though amyloid plaques are associated with many forms of the disease.

Evidence suggests that AD is more than one thing. A vaccine against amyloid plaques may not prevent brain decay in patients with clinical diagnoses, because about a third of them are missing postmortem.

If this vaccine can make it through human trials, it could bolster the brain health of millions. Let's hope the researchers find a commercial partner soon.

The results so far are very exciting and testament to the scientific expertise of the team.

The treatment could change the lives of many patients.

The study was published.