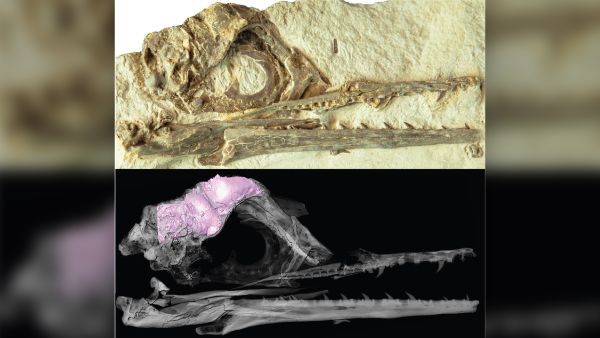

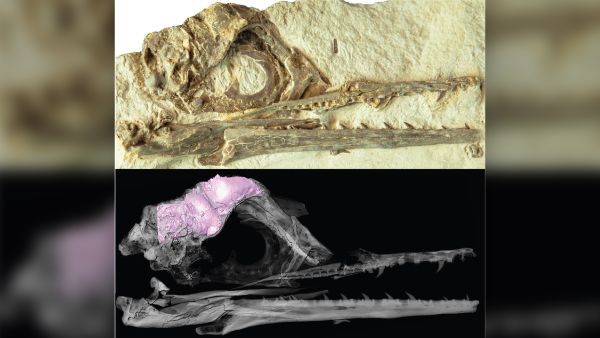

Photo of Ichthyornis' fossil (top) with digital brain reconstruction (bottom). (Image credit: Torres et al; CC BY 4.0

The collision of the dinosaur-killing Asteroid with Earth 66 million years ago triggered a series of horrendous events. These included shockwaves. wildfires. acid rain. tsunamis. volcanic eruptions. Nuclear winter-like conditions. This caused about 80% of all animal species to die. However, there were some survivors: the birds.

Why did some bird lineages survive while others died? A new study on an ancient bird skull shows that birds that survived the cataclysm had larger cerebrums or forebrains. This is the area of the brain that was most affected by the event.

It's unclear how large forebrains saved birds from starvation. However, because the forebrain is responsible in many processes, "it likely had something to do with behavior plasticity -- the birds that had larger forebrains could modify their behavior quickly enough to keep pace with how fast their environment was changing," Chris Torres, National Science Foundation postdoctoral researcher in the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, said in an email to Live Science.

Related: In images: Fossilized dinosaur brain tissue

The July 30th online publication of the Science Advances journal was followed by a Nov. 2 online presentation at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual conference. This year, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it impossible to attend the event.

Bird brain

Bird bones are fragile and rarely fossilize in three dimensions. Scientists seldom get a chance to see the inside of the skull, where the brain used to be, because they are difficult to view. Researchers discovered a partially 3D fossil of Ichthyornis, an old toothy bird, a few years back in Kansas. It was dated to between 87 million and 82 million years ago.

Torres, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin's Department of Integrative Biology, said that the skull was nearly complete. "This fossil preserves the majority of the bones that make the skull and gives us our first complete look at many of them."

Torres and his coworkers used X-ray computedtomography (CT), scanning to digitally reconstruct Ichthyornis’ facial skeleton, and brain structure. Analyzing the brain structure revealed that Ichthyornis, an ancient bird, had a brain more like those of dinosaurs than it was like the brains living birds.

Brain shapes of Archeopteryx, Ichthyornis, and other dinosaur-age birds had brains more like those of living birds than they did to those of ancient dinosaurs. The brain structure of living birds is unique, with a large cerebrum. This feature likely saved their ancestors from mass extinction. Chris Torres, image credit

Torres stated that living birds have "enormous foebrains in comparison to the rest" of their brains. Today's birds have forebrains that are larger than those of dinosaurs and ancient birds. Torres explained in an email that Ichthyornis was a close relative of living bird species but didn't have the same forebrain as living birds.

Torres suggested that the ancestor of all living birds may have had a big forebrain that gave them an evolutionary advantage. This helped them survive the "catastrophic worldwide climate change that most likely occurred during that mass extinct," Torres stated.

But, Ichthyornis' brain had a remarkable feature: a "wulst". This structure was previously only found in birds after mass extinction and is believed to be a sensory and visual processing center that plays an important role in flight. A wulst was discovered in a Mesozoic bird, or dinosaur-age bird. This discovery shows that ancient bird brains are more complex than we thought.

Brain structure analysis revealed that bird brains did not evolve in a linear fashion over time. Instead, they developed from a complex mix of brain structures. Jack Tseng, assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology at University of California, Berkeley, and assistant curator at Museum of Paleontology was not involved in this study. He said, "It's certainly not a linear progression of all things becoming more complicated or better adapted." "There are bits and pieces that have been added over time in different combinations."

Original publication on Live Science