People ask me questions about black holes whenever I speak about them. They worry that they will get too close to Earth and endanger us all.

Scientists like to refer to the odds of this happening as "vanishingly small". The difference between 0 and 0 is so small that it doesn't matter. The galaxy is large enough that only a very small percentage of stars can become black holes.

They are not extinct, however. They are likely to number in the millions in the Milky Way. This sounds scary until you realize that there are literally trillions of cubic light year out there for them to be completely isolated in.

These would be known as stellar mass black holes. They can have masses up to 100 times that of the Sun. You will also find larger black holes called intermediate mass black. These are a fraction of the Sun's size, and can be as large as a few hundred to several hundred thousand. I wonder how many there might be.

An international team of astronomers set out to discover the truth. Although we don't know the exact mechanism of intermediate mass black holes (or IMBHs), we believe they are found in small galaxies and galaxies similar to the Milky Way. One galaxy such as ours may have many small galaxies, or satellites, orbiting it at once. It could have even encountered thousands of them during its lifetime.

Structure of the Milky Way: Flattened disk with spiral arms. (Seen edge-on, left and right), with a central bulge and a halo. It is indicated where the Sun lies about halfway out. Credit: Left: NASA/JPL-Caltech; right: ESA; layout: ESA/ATG medialab Photo: Left: NASA/JPL-Caltech; right: ESA; layout: ESA/ATG medialab

A dwarf galaxy that passes too close to or through our galaxy could be in trouble. The much larger gravity of the Milky Way would rip most of its stars apart, leaving only the core. Many dwarf galaxies have an IMBH at the center, or off-center. This holds many stars tightly. It's possible that the IMBH could keep them, even after our galaxy has cannibalized most of its stars.

Astronomers used physical models of black hole, dwarf galaxies and stars to first determine how such an object would look. They call them hypercompact star clusters because they are literally only a few light-years across. This includes the colors and density of the stars.

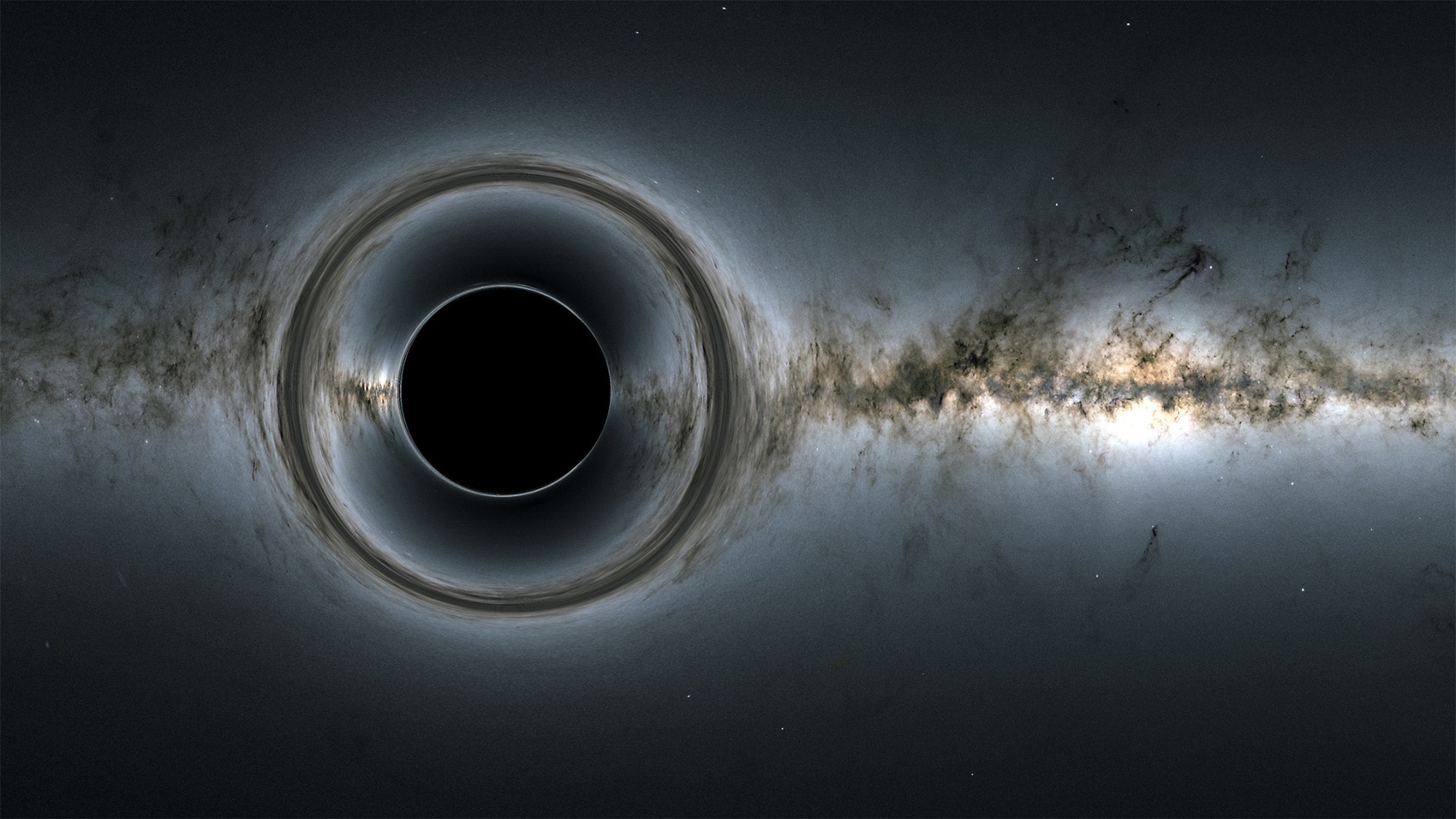

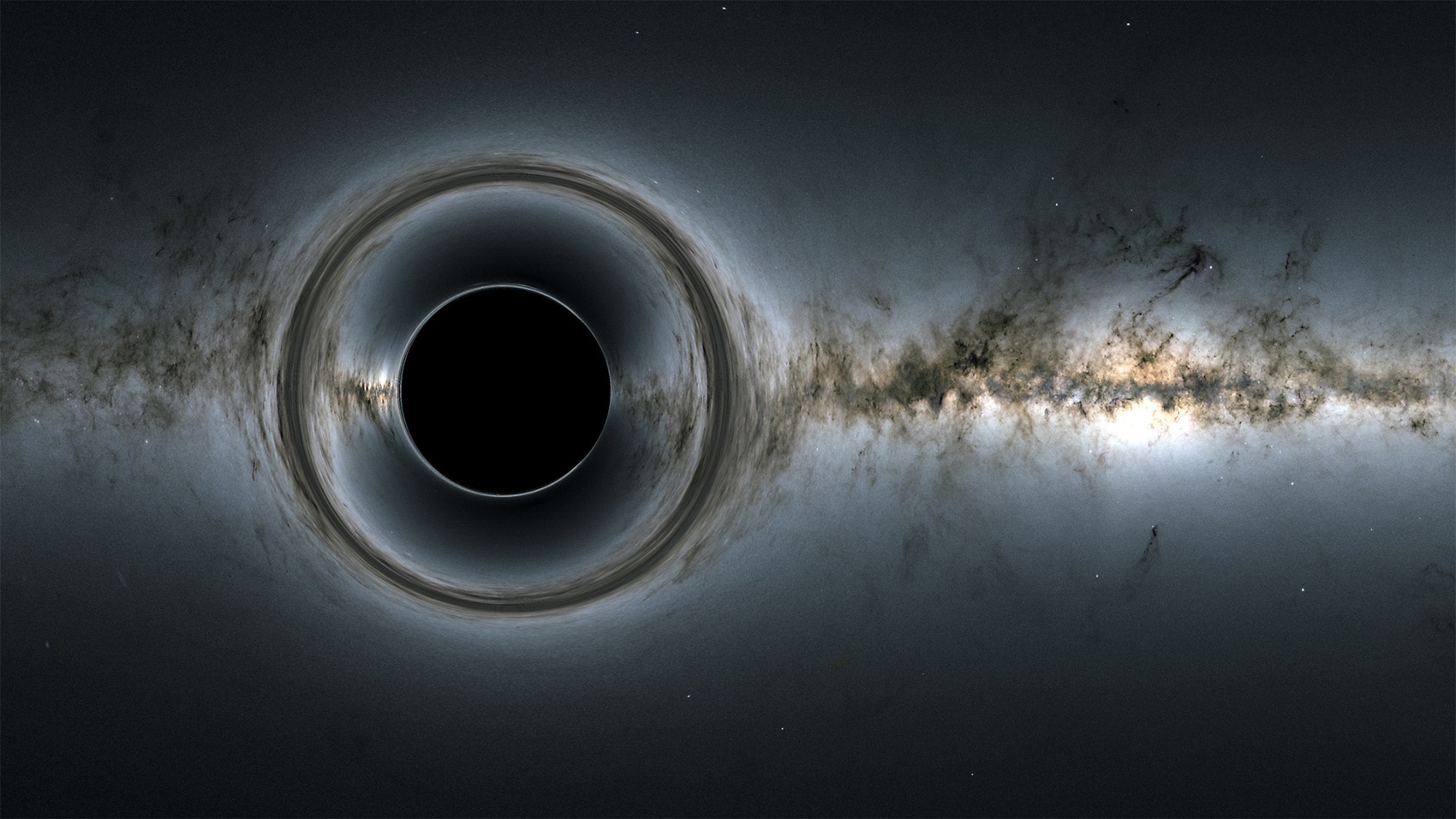

Illustration of a black spot drifting across the sky against a background of stars, dust and gravity. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center; Background, ESA/Gaia/DPAC. Photo Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Background, ESA/Gaia/DPAC

The European Space Agency observatory Gaia was then used to map the positions, motions and distances for well over a million stars in our galaxy. They used their models of clusters to search for spots in the sky with unusually many stars. All the stars were at the same distance, and all of them moved through space.

Gaia's ability to see faint stars is remarkable, but it can't tell if these clusters are hypercompact. The astronomers used their candidate list as a guide to determine what these objects looked like in DECam Legacy Survey. This is a wide-field sky survey taken by the Dark Energy Camera which can see much more fainter stars.

The result? They found 86 candidates in Gaia observations and DECam observations, covering 8,000 square degrees, or a fifth of the sky. The number of candidates that were found to be supercompact stellar clusters orbiting an intermediate-mass black hole was zero. Oof.

None of them met the requirements. Some stars had stars of different ages (the cluster star should be the same age), or stars with colors that didn't match.

The Omega Centauri, the largest globular orbiting the Milky Way, is the mighty Omega Centauri. Credit: ESO/INAF-VST/OmegaCAM. Acknowledgement: A. Grado, L. Limatola/INAF-Capodimonte Observatory

I have to admit that I was disappointed to read this section of the paper. IMBHs can be very difficult to track down and this clever idea is to help you find them. But it isn't over. Their survey missed clusters, so there could be more. Their criteria are dependent on models, so it's possible that their models are wrong. They predicted that they would find approximately 100 clusters based on the models they used. Maybe the stars have all disappeared from the cluster over time, leaving only the IMBH and surrounding stellar mass black holes. Larger objects are more likely to be at the center of a cluster, while smaller objects can fly off. This would make them invisible. Perhaps dwarf galaxies don’t have enough black holes to keep their stars safe, and so the clusters aren’t there.

They also note that the'scopes soon to be online, such as the massive ground-based Vera Rubin Obeservatory and the space-based Euclid, Nancy Grace Roman Telescope could still find these clusters and possibly even see them in nearby galaxies.

It could also be used to identify clusters in Milky Way that may have been stripped nuclei from former galaxies. These are known to exist. The "globular cluster M54" is either the nucleus or a remnant of the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy, which our galaxy is currently eating. It also once belonged to the Omega Centauri (so bright and large it can be seen by the naked eye!). It is possible that this galaxy may have ingested the remains of an earlier masticated one. We also see many stellar streams, which are long linear ribbons made of stars from smaller galaxies or clusters. (Gaia was actually instrumental in discovering these), so we know that the Milky Way has been busy being a galactic gourmand for eons.

It is reasonable to believe that hundreds of these black holes could quietly orbit around the center the Milky Way. All we have to do is figure out how to spot them. What if there's none? That would be quite interesting. We learn something about the distant past galaxy that we live in.