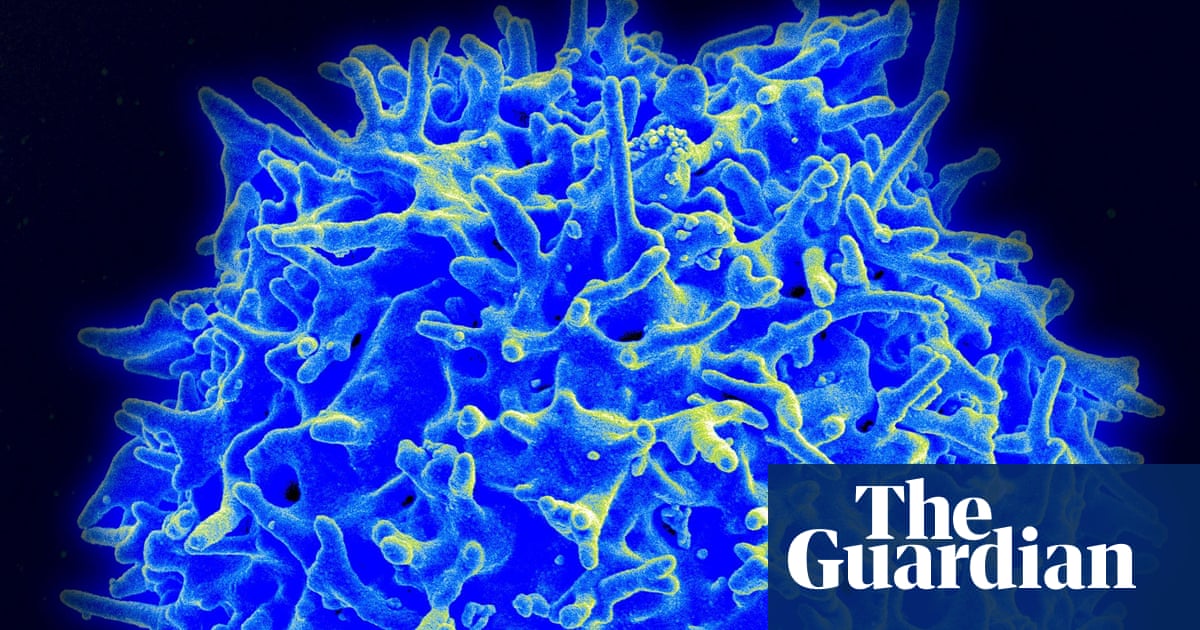

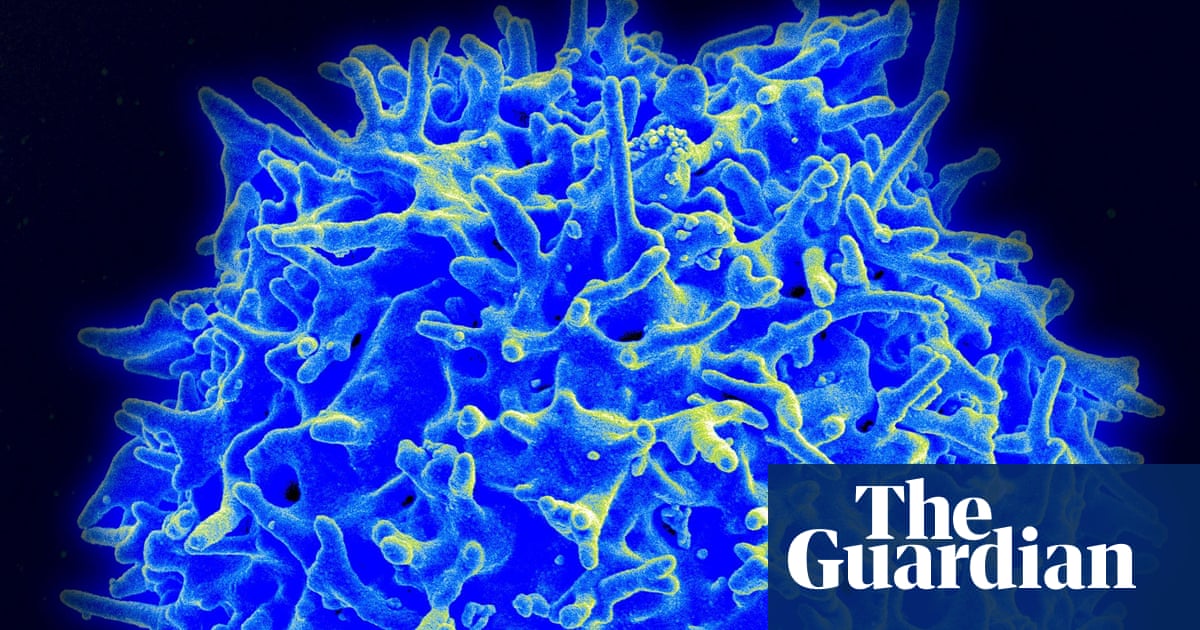

Everyone knows the person who has never been positive for Covid-19 despite having their entire family infected. Scientists now know why some people get "abortive infections". This is when the virus enters the body and is cleared by T-cells.

This scenario was matched by approximately 15% of healthcare workers tracked in London's first pandemic.

Scientists believe that the discovery could open the door to a new generation vaccines targeting T-cell responses, which could provide longer lasting immunity.

Leo Swadling (an immunologist at University College London) was the lead author of this paper. He said that there is anecdotal evidence that people are exposed to the virus but do not succumb to it. We don't know if these people were able to avoid the virus completely or if they had natural immunity.

In the latest study, healthcare workers were closely monitored for signs of infection during the first pandemic wave. Despite the high risk of being exposed, 58 people did not test positive to Covid-19. These people had a higher number of T-cells that were reactive against Covid-19 in blood samples than those taken before the pandemic. This was in contrast to people who had never been exposed. There was also an increase in another marker of viral infection.

This suggests that some people may have memory T-cells from prior infections with seasonal coronaviruses, which cause common colds. These cells protected them against Covid-19.

These immune cells "sniff" proteins in the replication machine - which is a part of Covid-19 - and in some cases this response was fast and potent enough to clear the infection at its earliest stage. Swadling stated that these pre-existing T cells are ready to recognize SARS-CoV-2.

This study expands on the range of possible outcomes after Covid-19 exposure, which can include severe illness or escaping infection completely.

Alexander Edwards, an associate professor of biomedical technology at University of Reading, stated: "This study identified [a] new intermediate outcome - sufficient virus exposure to activate your immune system, but not enough for symptoms, detect significant amounts of virus, or mount an antibody reaction."

This finding is especially significant as the T-cell arm in the immune system tends to confer a longer lasting immunity than antibodies. Nearly all of the Covid-19 vaccines are focused on priming antibodies to the vital spike protein that allows SARS-CoV-2 to enter cells. These antibodies provide excellent protection against severe illnesses. The immune system deteriorates over time, and it is possible for spike-based vaccines to fail because this area of the virus can mutate.

The T-cell response, however, does not fade as quickly. Furthermore, the internal replication machinery it targets is highly conserved across coronaviruses. Therefore, a vaccine targeting this area would likely protect against new strains and even new pathogens.

Andrew Freedman (a Cardiff University School of Medicine reader in infectious diseases), said that the study's findings could help to design a new type of vaccine. A vaccine that primes T cell immunity against viral protein targets shared by many coronaviruses could complement spike vaccines that induce neutralising antibodies. These components are part of the virus so antibodies are less effective. Instead, T-cells are used.