These statistics are shocking. The statistics are stark. In the second pandemic wave, people of Pakistani heritage were twice as likely to die due to Covid-19 as those with white European origins. The risk for those with Bangladeshi heritage was three to four times.

Because of the disproportionate effects of the pandemic, policymakers have had to ask why certain people have suffered worse outcomes than others.

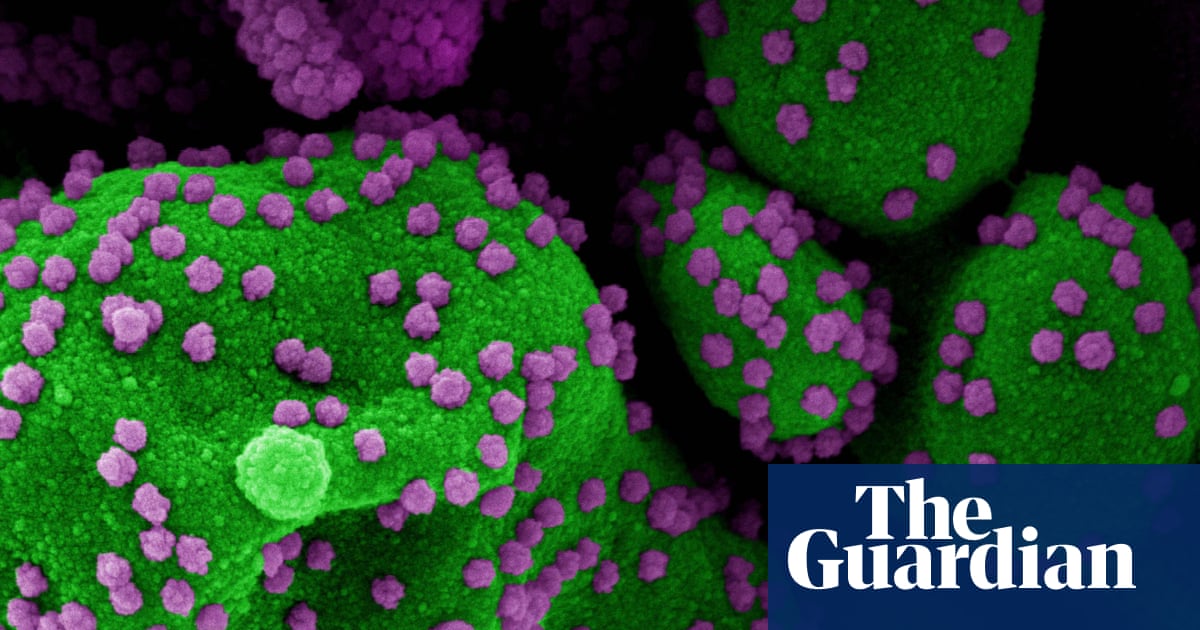

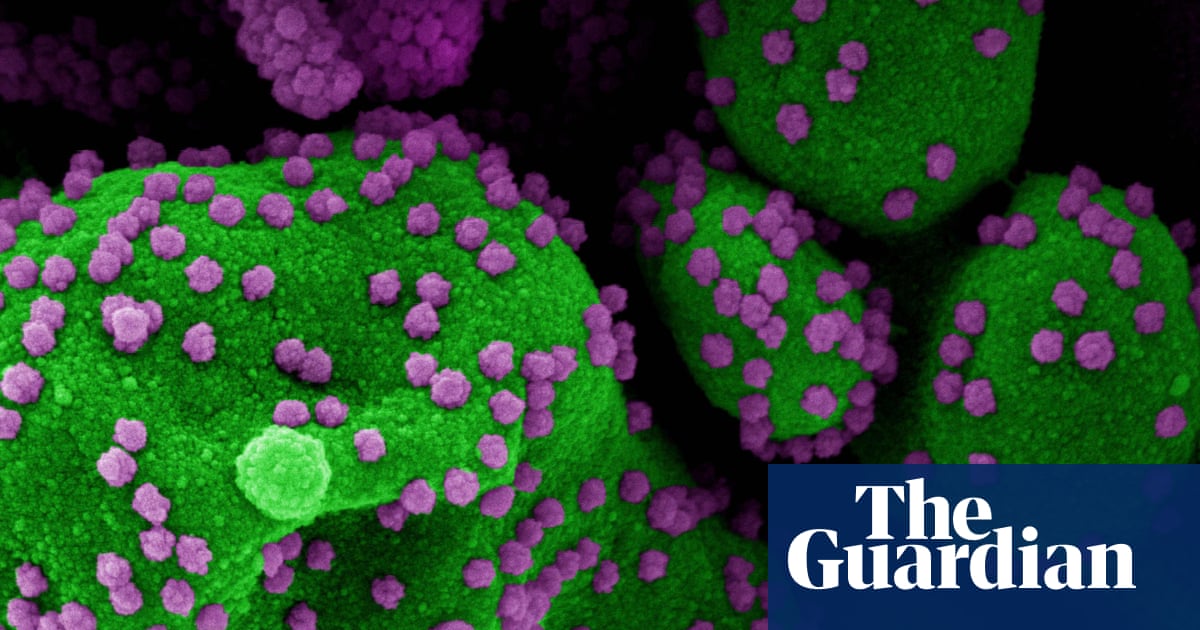

It seems that genetics could play a part in the explanation. It has been discovered that a gene alters how the cells of the lining the lungs react to the Covid-19 virus.

Your cells will respond faster to the virus if you have the low-risk variant. This defense mechanism is slower and more susceptible to respiratory failure and death than the high-risk variant.

According to the University of Oxford researchers, 60% of people with South Asian heritage are carriers of the high-risk gene. This compares with 15% of white Europeans and 2% of Caribbean or black African heritage.

These findings provide a plausible explanation to the unanswered risk that continues in south Asian communities in the UK. Black Africans of heritage could be a particularly vulnerable group during the first wave. The additional risk could be explained by factors like occupation, underlying health problems, and where one lives. These people had much better outcomes during the second wave.

However, this was not true for people of south Asian descent. ONS data shows that despite accounting for socio-economic factors, people of Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani heritage still faced a 50% risk increase. This was something scientists have struggled to explain.

Although the genetic explanation of this persistent disparity is possible, it should be considered with caution. The first step is to confirm the finding using genetic data from Covid patients of different ethnicities. This serves to remind people from ethnic minorities that they are not represented in the large genetic databases, which support many discoveries about genes and health.

A database of almost 200,000 genomes has provided evidence that the LZTFL1 gene is found in 60% of people of South Asian descent and 2% of Africans. 85% of these genomes are of European descent.

Scientists cannot be certain that these figures are applicable across entire societies without better representation of these databases. This is especially true since social definitions such as ethnicity often do not correspond to the distribution of risk gene through the population.

Even if genetics are responsible for a certain percentage of risk, policymakers cannot use this to their advantage and abdicate responsibility. Socio-economic factors play an even greater role for south Asians. Consider factors such as the risk of infection in the workplace and the effects on children growing up in multi-generational families.

If the genetic finding is confirmed there are policy implications, including offering booster vaccines to people of south Asian heritage on a priority basis.