Scientists may have discovered a planet in another galaxies for the first time in human history.

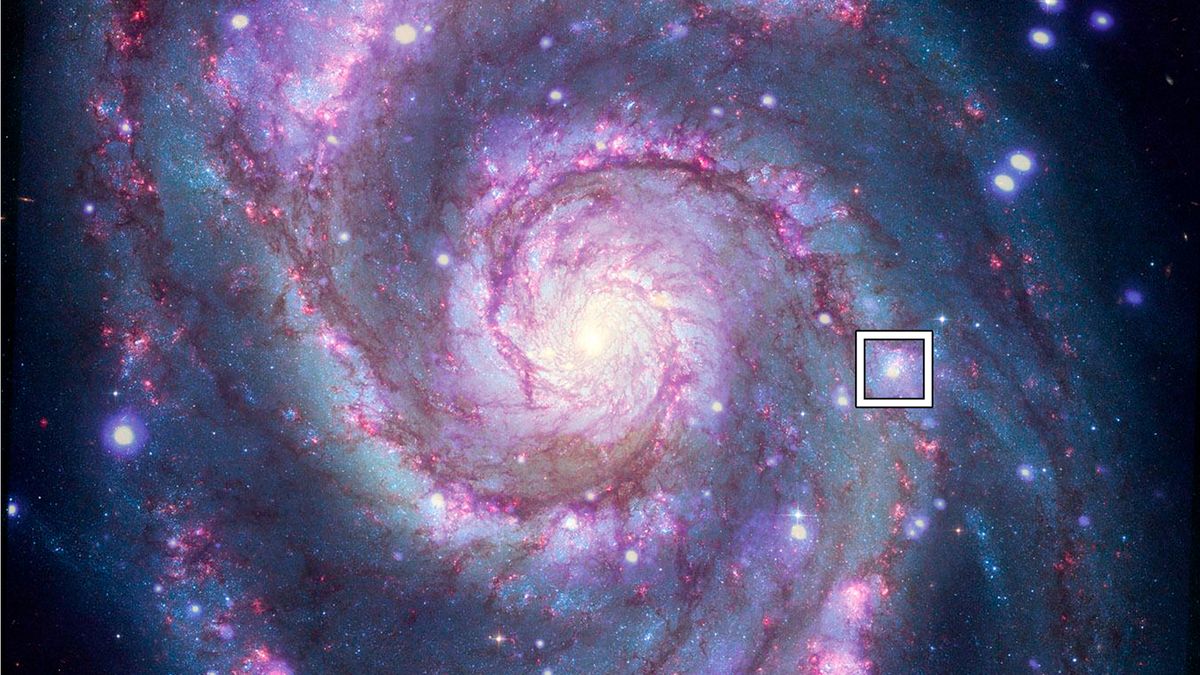

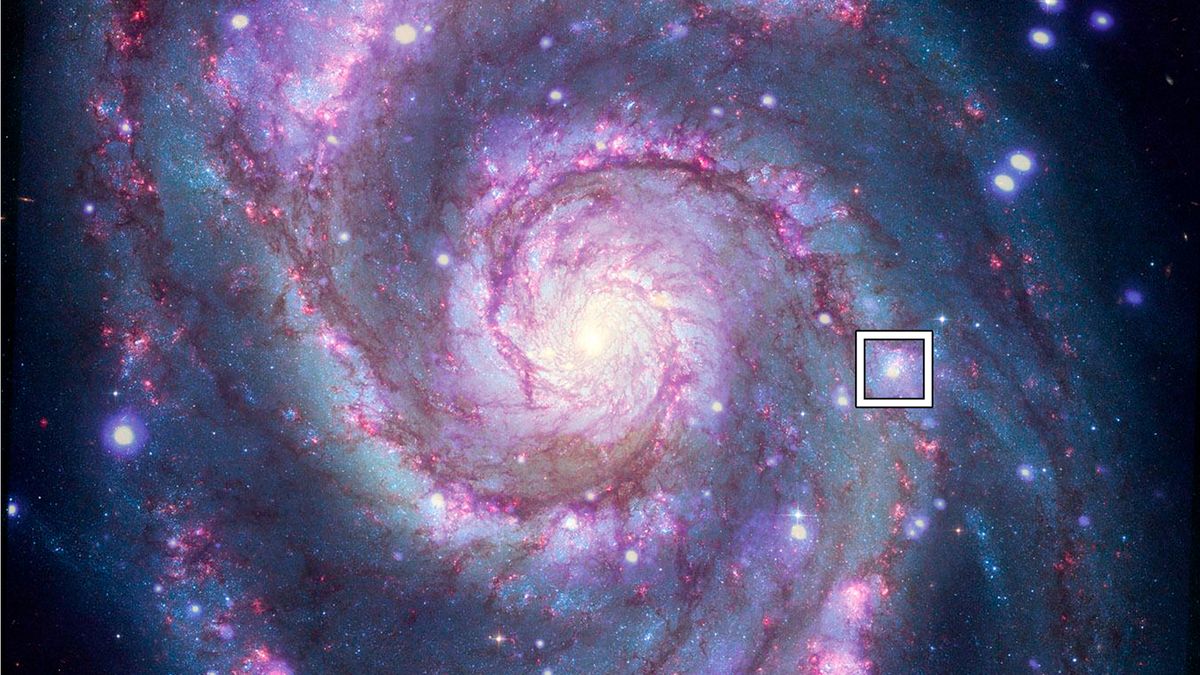

M51-ULS-1b is a potential exoplanet that lies 28 million light years away in the spiral galaxy Messier 51, also known as the Whirlpool galaxies. This discovery could just be the tip of an iceberg. There are many more exoplanets beyond the Milky Way.

Rosanne Di Stefano (an astrophysicist at Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) was the one who led the search that found the object.

Related: Gallery of the strangest alien worlds

Looking beyond our galaxy

Artist's illustration of a neutron-star around a black spot in the Whirlpool galaxy M51, which may be home to an exoplanet. Image credit NASA/CXC/M. Weiss)

We want to open up new avenues for discovering other worlds... Rosanne di Stefano, astrophysicist

Astronomers used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton telescope to study three galaxies beyond our Milky Way. They looked at 55 systems in M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, 64 in Messier 101 (M-101) or the "Pinwheel Galaxy", and 119 in Messier 104 (or the "Sombrero galaxies".

Transits are when an object passes in front of a star and transits. The team found the object in M-51. It blocks some star's light, creating a short dimming. This method has been used by scientists to find thousands of exoplanets (planets that are not in our solar system but still within our galaxy), previously.

1992 was the year that exoplanets were first discovered. Since then, most have been located less than 3,000 light years from Earth.

M51-ULS-1b is 28 million light years away and would be the first exoplanet to be found in another galaxy.

Related: 7 methods to find alien planets

This graphic shows the position of a black hole or neutron star and the companion star. It also shows the orbit of an exoplanet that may be in orbit. Image credit NASA/CXC/M. Weiss)

The team headed by Di Stefano used Chandra for X-ray brightness dips to spot the planet. Planets that pass in front of stars can block out Xray emissions completely because Xrays are created by tiny areas on them. Researchers could observe a more visible transit instead of subtle dimming of the optical light. This could allow researchers to see objects further away.

Di Stefano stated, "We are trying open up a new arena for discovering other worlds by searching planet candidates at Xray wavelengths. This strategy makes it possible for them to be discovered in other galaxies."

The possible exoplanet was found in the Whirlpool Galaxy in a binary system that orbited two large objects, either a neutron or black star.

They witnessed the transit for three hours, and the Xray emissions dropped to zero. They were able to determine that the object was likely about the same size as Saturn, and orbits the neutron star (or black hole) at twice the distance of Saturn from our sun.

Confirming a discovery

Artist's illustration of a neutron-star around a black spot in the M51 Whirlpool Galaxy, which may be home to an exoplanet. Image credit: Xray: NASA/CXC/SAO/R. DiStefano, et al. ; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI/Grendler)

This could be the first time that a planet has been confirmed in another galaxy. It could also open up new avenues for planet study and detection. These observations don't prove that Chandra's object is a planet. Researchers said that more data is needed to support this assertion.

The object will not transit again in front of its star for 70 years. Therefore, scientists won't be able to observe it again until then.

"Unfortunately, to confirm that our planet is visible, we would probably have to wait decades before we see another transit," Nia Imara (a researcher at the University of California at Santa Cruz) said in the same statement. We wouldn't be able to know when we would look because of uncertainties around the time it takes to orbit.

Researchers acknowledge that it is possible but unlikely that dimming could result from something like a cloud passing near the star. The team shared their findings and data with other scientists. This could verify their findings and help move the research forward, even though there are still decades before the next transit.

"We know that we are making an exciting, bold claim so we expect other astronomers to look at it very carefully," Julia Berndtsson (a Princeton University researcher in New Jersey) added in the same statement. "We believe we have a strong argument and this is how science works."

This work was published in Nature Astronomy on Oct. 25, 2012.