A red blood cell's job description is not too complicated. Pick up oxygen, drop off oxygen. Rinse, wash, repeat. We should give all the credit to their white cell sisters when it comes protecting the body from infection.

A new study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, USA, has shown that red blood cells play an important role in inflammation. This could be a significant difference in your life.

Scientists suspected that red cells could play a role in repelling invaders as early as the middle century. Researchers discovered receptors in red blood cells that respond to inflammatory chemicals called cytokines by the 1990s.

All of it pointed to something. There was also the mysterious loss of blood cells anemia, which is often associated with sepsis.

According to Nilam Mangalmurti (pulmonologist), acute inflammatory anemia can often be detected early in an infection like parasitic infections that cause malaria.

"Acute anemia is a condition that occurs when someone becomes critically ill due to trauma, sepsis, COVID-19, a bacteria infection or parasite infection. This has been a mystery for a long time."

Mangalmurti's team demonstrated just a few years back that red blood cells can scavenge free-floating mitochondrial DNA from damaged tissues. This triggers an immune response that regulates inflammation in the lungs.

The puzzle was incomplete. How can a small piece of DNA from our bodies transform an oxygen-carrying cell to an infection-fighting device? Why do they disappear?

The protein that grabs onto DNA could hold the key to the key. They are called toll-like receptors or TLR and can be found on sentinels such as the microbe-munching macrophages.

Initial tests on red blood cells from chimpanzees and humans confirmed that they exist. The researchers discovered that sepsis and COVID-19 patients have more receptors than they thought, thanks to the recent analysis of blood samples.

The TLR9 receptor quickly removes DNA fragments, some of which bear a striking resemblance with sequences found in many bacterial and virus segments of nucleic acids.

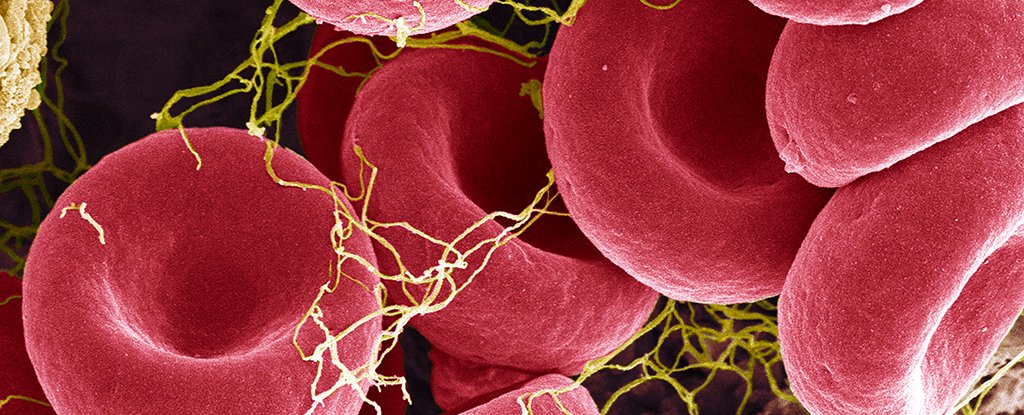

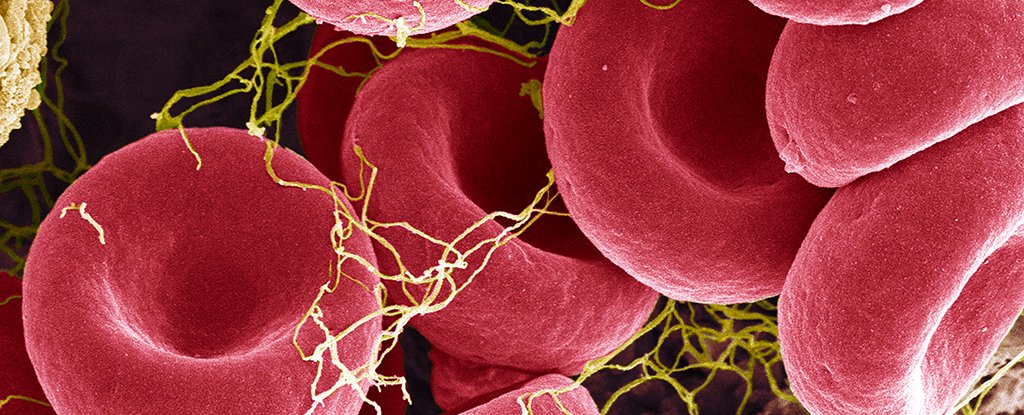

These DNA-triggered red blood cell looked shockingly abnormal under carefully controlled laboratory conditions. Their concave 'donut shape was warped.

This change in morphology can be a sign of sepsis. It was obvious that the team was on a right track under these laboratory conditions.

The malformed red blood cells were quickly swallowed by macrophages and disappeared. This in turn set off an inflammatory chain reaction that caused a number of messengers to be released, which would prompt the immune system's swift response.

The parasites were confirmed by tests on mice infected. The red cells of mice infected with parasites had higher levels of mitochondrial DNA than those from healthy animals.

Inflammation can cause inflammation in areas of the body that aren't at risk of infection. This is especially true for people with autoimmune diseases. It would be a great help to find ways to stop red blood cells reacting to free-floating mitochondrialDNA.

Acute anemia patients at high risk would be saved by this.

Mangalmurti says that blood transfusions are the only option for patients who have become anemic in the ICU (intensive care unit). This is almost all of our critically ill patients.

"Now that we have more information about anemia's mechanism, we can look into new treatments for acute inflammatory anemia. These therapies don't require transfusions and include blocking TLR9 in the red blood cells.

This research was published by Science Translational Medicine.