Although your internal organs change over time, they rarely disappear without trace. Things are more complicated for baby octopuses.

Before being born, embryonic octopuses grow hundreds of microscopic structures called Klliker's Organs (KO).

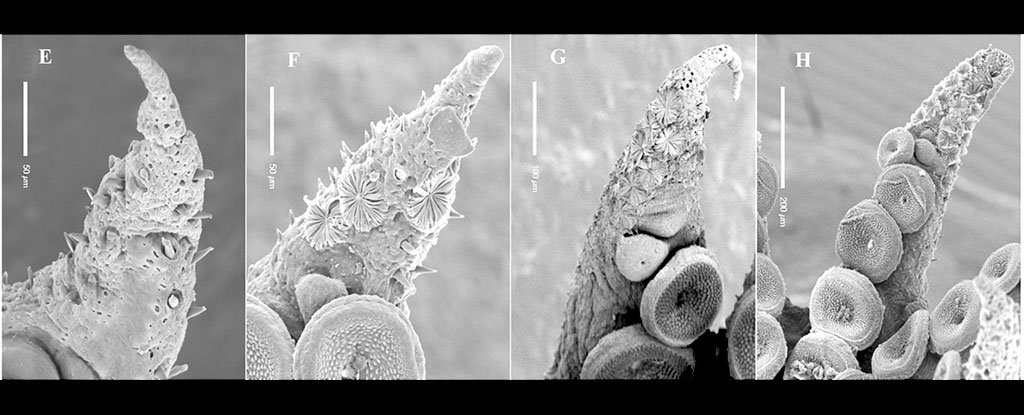

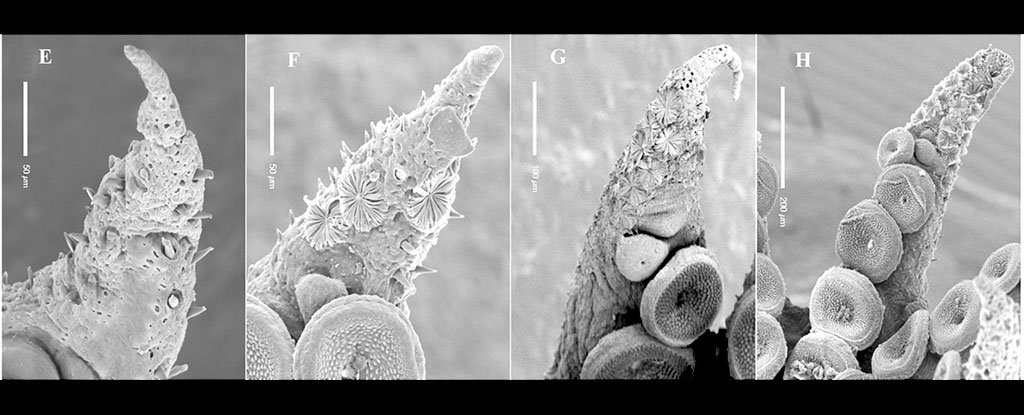

These tiny organs cover every surface on the octopus’s body. Sometimes they hide in tiny pockets under the skin and other times extend (or "everting") as tiny umbrellas.

Each organ can open once it is eversted, revealing bristly fibers.

Roger Villanueva (a researcher at the Institut de Cincies del Mar, Spanish National Research Council) told Live Science via email that KO looks like a broom when it is partially everted. "When fully everted, KO appears half of a dandelion bloom."

Similar: 8 Crazy Facts About Octopuses

Close-up of the KO

These microscopic flowering organisms have been known by biologists for many decades, but no one can say for certain what they are or why embryonic octopuses lose all their bristly bits and pieces long before becoming adults.

Villanueva's recent research and that of his collaborators sheds light on these mysterious organs.

The researchers published a study in Frontiers in Marine Science's May 2021 issue. It examined 17 species embryonic octopuses. They used a light-sheet microscopy technique to examine the samples. This involves submerging the sample in liquid to make it transparent and shining light through it to reveal hard-to-see structures.

Out of 17 species that were studied, 15 had Ko. The two that did not have KO were both holobenthic oysters. This means they are large and live in deep seas.

Nearly all 15 species with KO were born planktonic, meaning that hatchlings are very small and can swim higher in the water column as their bodies grow and change into adulthood.

(Villanueva et al., Frontiers in Marine Science, 2021)

Above: These images depict the eruption and eversion sequences of Klliker’s organs on a variety of young male octopuses.

The team discovered that KO are evenly distributed across young octopuses' bodies and tend to be equal in size regardless of embryo size.

The researchers also found that if all of the KOs are open, the animal's total surface area can increase by two-thirds.

Researchers believe these discoveries may hint at the mysterious purpose behind KO.

Villanueva, the study's principal author, stated in a statement that "[We] believe that the organs might be used by young octopuses for increasing their surface-to volume ratio."

Young octopuses have the ability to increase or decrease their surface area. This is a useful trait that may help them to navigate through ocean currents or resist them. This is especially important for planktonic hatchlings who spend most of their lives moving in the direction of the currents.

Researchers hypothesized that hatchlings could conserve energy by deploying or retracting their KO.

There's another possibility, however. Researchers point to a 1974 Aquaculture study that showed that KO, just like crystals can reflect light in multiple directions. Researchers suggested that this refractive ability could be used to smear hatchlings in water, making it harder for predators.

Camouflage is a function of KO. This could explain why many octopuses who live near the ocean floor aren't able to grow KO. In the dark, lightless depths there is no need for camouflage.

However, it's possible. Researchers still haven't figured out the purpose of these unusual organs, despite looking at them more closely than any other study.

Biologists may be able to find out more from future observations of wild octopuses hatching. The researchers are content to show the curious beauty of tiny cephalopods as they were, for now.

Montserrat Colll-Llado (a co-author of the study and a mesoscopic imaging specialist at The European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Barcelona), said that it was fascinating to look inside the tissues and organs hatchlings and juvenile octopuses at cellular level. It's like going into a small corner of a city and discovering new things. But it's even better.

Similar content:

Photos: Deep-sea Expedition discovers a metropolis of Octopuses

Photos: Eggs protected for 4.5 years by an amazing 'octomom"

Photos: A ghostly dumbo octopus moves in deep sea

Live Science originally published this article. You can read the original article here.