Last update on. From the section Football

Tonsser United, a group of youth players from various amateur clubs, will take on Paris St-Germain's academy August 2019.

Simon Hjaere was anxious.

He was one of a few spectators who watched the game from the sidelines in a Parisian suburb as the August sun set. Two teenage teams marched out onto the pitch in front of him.

One wore the Paris St-Germain badge's familiar dark blue and red shirt with the Eiffel Tower.

One wore black trim and white shirt. Their crest featured a simple outline of a football against a neon background.

Hjaere said, "I was wearing all my nerves out of my skin." It was like watching my national team Denmark play in a big match.

It was an experiment. It is possible to have faith in something. You can also believe in something. But it still needs 11 children.

The white team had no home or history. Two days earlier, the players had only seen each other twice.

They shared two things. They shared a hunger to prove that they had been wrongly overlooked. An app for their smartphone.

Tonsser was used by all. The app tracks the progress of unsigned youth athletes and was founded by Peter Holm and Hjaere in 2014. The app allows you to rank your team-mates and rivals, upload footage, and submit stats.

The best are eligible to apply to Tonsser United, the team in white.

Hjaere had presented the app numerous times in business meetings and boardrooms. The pitch was a test of Hjaere's claim that there is vast untapped talent outside of professional clubs.

Holm stated, "We looked at football and technology and what was lacking."

"We were unable to understand why around 55,000 professional footballers are in the world. They are part of an over-saturated ecosystem with companies monitoring stats and cameras filming most of them. There is also a fairly well-functioning transfer system. There are also 100 million youth players that are not yet mapped.

It is hard to identify potential players. This was an inexplicable problem, especially as youth footballers are among the most passionate and aspirational groups in the world.

"There appeared to be this mismatch."

Most clubs use old-fashioned social networking to bridge the knowledge gap. Scouts search the local leagues for tips, then hustle to find the next big thing.

Sometimes, however, prospects slip through the cracks.

Famously, Jamie Vardy, in his twenties, was on the books at a Sheffield factory that made prosthetic limbs.

Michail Antonio, West Ham's Michail, was at non-League Tooting and Mitcham in a similar age.

Big clubs also missed former England internationals Ian Wright and Chris Waddle, Stuart Pearce, Peter Beardsley, and Stuart Pearce at a young age.

These oversights, according to Hjaere & Holm, are not uncommon.

They feel that scouting systems can be biased, blind spots, or just plain bad luck. A player's performance on any given day could end their chances of winning.

If players rank one another, and if a critical mass is used to regulate those assessments, if they're backed up with cameraphone footage or validated stats then the "wisdom" of the crowd shines through.

Hjaere says, "If you want the best player in the team, you should ask the players who measure themselves against each other constantly."

Everyone has biases. One is that we as individuals look for evidence that supports a particular pattern of performance, rather than those that challenge it.

"Clubs believe they have all the information about their area, but this information is only available through people with their own subjectivity. The biases build up over time. Personal recommendations are very fragile and can be used to make decisions.

Rasmus Ankersen, director of football at Brentford, has been a leader in the data-driven approach to football. Rasmus Ankersen, a Dane, combines his position with that of chairman at FC Midtjylland.

Rasmus Ankersen agrees. He is the director of football at Brentford and has pioneered a stats-heavy approach for recruitment which has allowed the club to punch well above its weight in both the Championship, and this season in the Premier League.

He was just appointed to the Tonsser Board.

He said that while judgments of young football players can be very snappy and based on subjective (and sometimes inaccurate) information, he explained to BBC Sport.

It is difficult to predict the future and spot talent in that age group. This is the truth.

"What we see is a race for the bottom in the competition for young talent. Clubs are making more decisions on younger and less experienced players. This increases the chance that you're making mistakes.

"Scouting reports can be subjective. They don't have to be the only thing we look at. Before making a judgment, we believe in increasing the sample size by getting many opinions about a player.

Tonsser is the only app that has successfully bridged the gap between professional youth clubs and unsigned youth players.

Ankersen has been one of the investors who have invested a total amount of 15 million euros in the company since its inception. Twenty-three clubs across Europe have used its data to locate talent.

Borussia Dortmund striker Erling Baaland, who is now one of Europe's most important talents, was a Tonsser user while he was with his Norwegian home team Bryne FK.

The app is used by more than 1.3 Million young footballers worldwide.

However, the most important thing in football is the scoreline.

Tonsser United – the team selected from the best app users - held Paris St Germain to a draw of 1-1 that day in Paris, which became the most compelling statistic of all.

The same players won against Lille, Marseille and Juventus.

Although they didn't win, the players Holm and Hjaere proved their point.

The team they put together was able to match some of Europe's strongest academies. They have maintained this feat with new players in tournaments across the continent.

Enzo Lefel, goalkeeper for top-flight Angers, signed after his penalty save allowed an under-15 Tonser United team beat Fulham to reach the Madewis Cup final in 2019.

Some of the most talented players on the app may not have been able to play for the team.

Borussia Dortmund striker Erling Brut Haaland used it when he was playing for third-tier Norwegian side Bryne. Wesley Fofana, Leicester's defender, was there before signing his first contract at St Etienne. Mikel Damsgaard of Sampdoria was, like many other members of the Danish Euro 2020 team, a former user.

All were signed by professional clubs, without Tonsser United involvement.

It has also made a significant impact on the lives of other players. The team has seen 65% of its players sign for professional clubs or go on trial.

Brentford has players like Fin Stevens (18-year-old fullback). Enzo Lefel (17 years old) signed for French top-flight team Angers after appearing for the club.

He said that Tonsser played a significant role in his confidence. "I knew I had the ability to sign for an academy.

My team-mates are like my family. We have a Snapchat group and we follow each other on Instagram.

When one of us signs up for a club, it goes off with congratulations messages. We can offer advice to others who haven’t yet signed a contract. We continue to motivate each other."

People need more motivation, advice, and support than others.

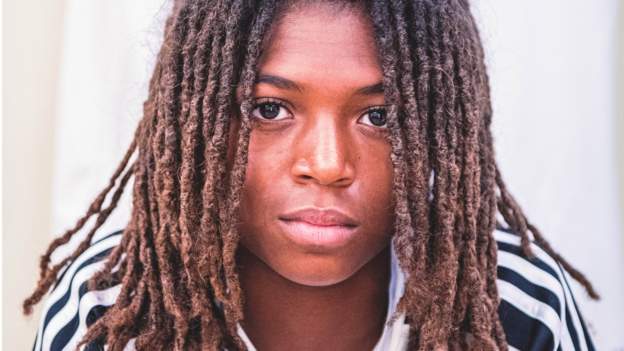

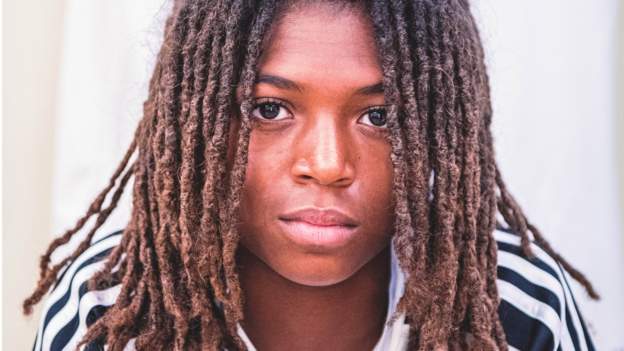

Issiaga Camara was a tall and rangy player in the mold of his idol Paul Pogba. He was part of the team that drew in PSG. Many clubs were impressed by his performance.

After his placement in foster care and immigration from Guinea, he had to submit incomplete paperwork.

Tonsser is helping him to sort out his situation and sign a professional contract.

Holm said that Holm was told by one of the players that Tonsser United was the national team for the underdog.

Some of Europe's most powerful people have been on the run from the underdog. It may change forever the way talent is selected in the richest sport on earth.