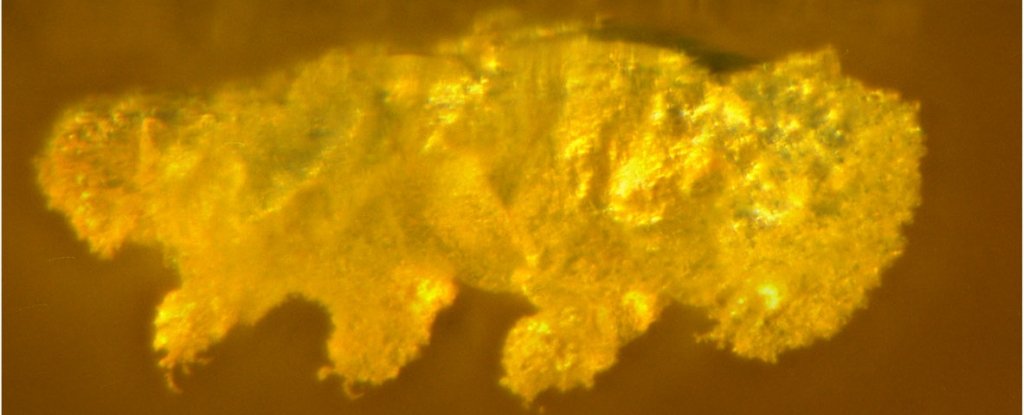

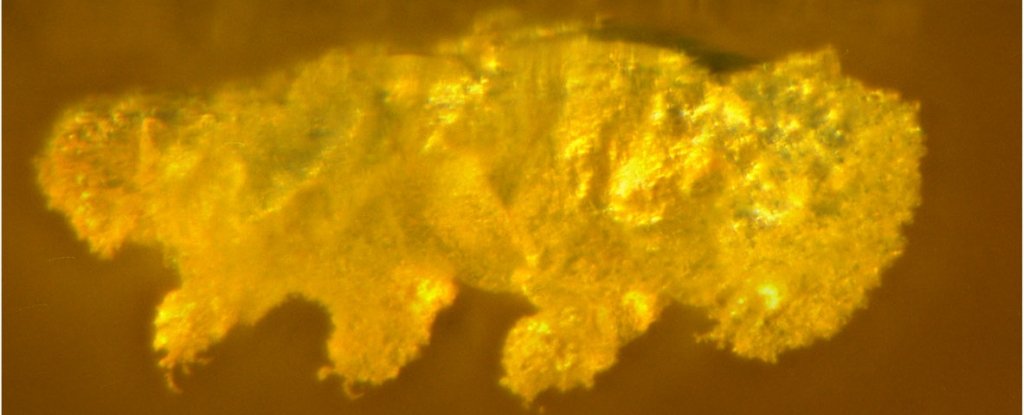

The fossilized tardigrade, found in Dominican Amber, is a rare branch in the family tree of these strangely indestructible beasties.

This specimen dates back to the Miocene (16 million years ago) and is the third tardigrade to be fully named and described in amber. Scientists believe this is due to their small size and inability to produce minerals that can withstand the ages.

The wee beastie can, at the very least, help us to understand the evolutionary history and evolution of tardigrades. This phylum has somehow survived every mass extinction that we know. It was named Paradoryphoribius Chronocaribbeus by its discoverers, and is a member the Isohypsibioidea superfamily of modern tardigrades.

Phil Barden, a biologist at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, says that "the discovery of a fossil tardigrade was truly a once in a generation event."

"What's so amazing is that tardigrades, an ancient lineage that is ubiquitous and has seen it all on Earth from the fall of dinosaurs to the rise terrestrial colonization of plants.

"Yet they are like a ghost-lineage for paleontologists with virtually no fossil record. It is exciting to find tardigrade fossil remains. This allows us to empirically track their progress through Earth history.

Amazing survivors, Tardigrades. They can survive in extreme conditions by drying out and reconfiguring their bodies.

They can withstand almost any temperature, including zero oxygen, freezing temperatures, high pressures and the vacuum of space. Their evolutionary history remains a mystery.

So smol! (Phillip Barden/Harvard/NJIT).

Dominican amber's tiny preserved tardigrade is microscopic and measures just over half of a millimeter. The researchers couldn't see the tiny details with a standard microscope so they used confocal microscopy.

A tardigrade's cuticle, made up of chitinous material, is easily excited using lasers in confocal microscopes. This causes it to fluoresce.

Researchers claim that the result is the most well-imaged tardigrade fossil. The images clearly showed the researchers the tiny claws and mouth apparatus of the tardigrade, as well as its foregut. They were clearly looking at something new.

Marc Mapalo, a Harvard University tardigradologist, says that even though it appeared like a modern tardigrade from the outside, confocal microscopy revealed it had a unique foregut structure that justified for us to create a new genus within the extant tardigrade superfamilies.

"Paradoryphoribius, the only genus with this unique character arrangement in Isohypsibioidea, is Paraadoryphoribius."

Scientists can also better study the evolutionary changes that tardigrades underwent over millions of years.

Paradoryphoribius is the only tardigrade fossil of the Cenozoic era. Two other fossils are older: Milnesium Swolenskyi was described in 2000 and Beorn Leggi, in 1964, is approximately 72 million years old, both from the Mesozoic.

(Mapalo et al., Proc. R. Soc. R. Soc.

Above: Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus autofluorescence under confocal microscope.

Even though there are few fossils available, even finding one can provide us with a lot of information to compare. The team was able, even just by dating the amber to establish a minimum age for Isohypsibioidea.

Mapalo stated that if you examine the external morphology and body of tardigrades, it is possible to assume that no changes have occurred."

"However, we used confocal laser microscopic to see the internal morphology and observed characteristics that were not present in extant species, but which are found in fossils.

This helps us to understand how changes have occurred over millions of years. This suggests that, even though tardigrades are the same externally as they are internally, there are some internal changes."

This discovery confirms that amber is an untapped resource for tardigrades. Amber is the best option because the animals are able to live in moist environments where trees may not be found. Also, their small frames cannot be easily fossilized (or they just live forever, who knows), amber seems like the best choice.

They are however small and it is possible that they may have been overlooked in amber deposits.

Researchers hope their discovery will inspire others to examine amber samples in order to learn more about this mysterious and hardy phylum.

Barden states that "we are only scratching the surface" when it comes understanding living tardigrade communities in places like the Caribbean, where they have not been surveyed.

"This study reminds us that we don't know much about the current living species of our planet, despite having a lot of tardigrade fossils."

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences published the research.