On a lovely fall afternoon, Liz, my wife, and I went to Great Crossing, Scott County to search (unsuccessfully as it turned out), for the farm of one Kentucky's most remarkable, but largely forgotten figures.

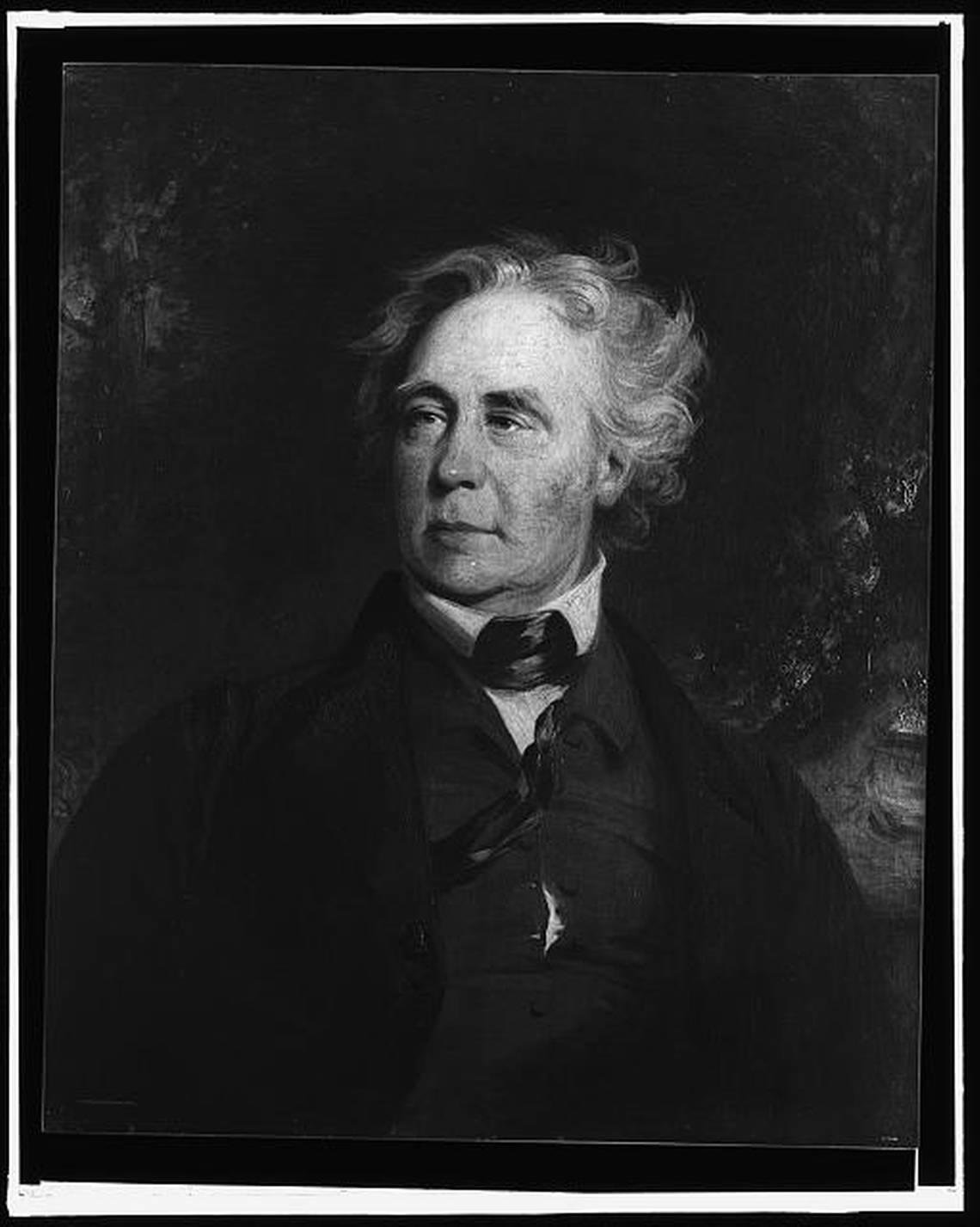

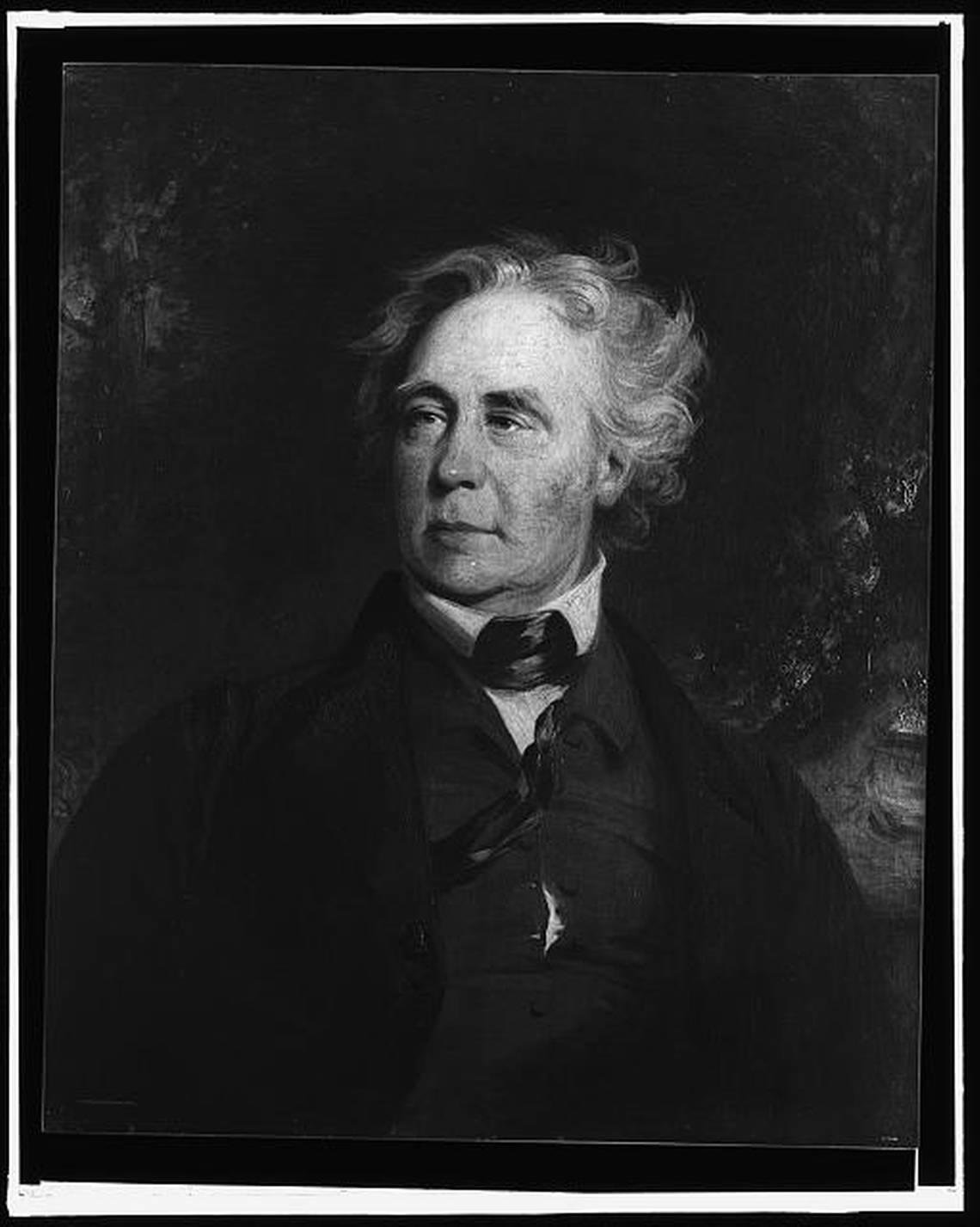

Richard Mentor Johnson (1781-1850) led a stranger-than-fiction life. He was the son of a prominent family in Central Kentucky and rose to higher heights than his relatives: he was a hero of War of 1812, U.S. representative and U.S. senator, and finally, vice president of America under President Martin Van Buren.

He defied all conventions along the way. His story shows how complicated and difficult it was to pin down our forefathers.

Johnson led a contingent of Kentuckians against British soldiers and Native American comrades in the 1813 Battle of the Thames. Johnson was wounded several times but he won the battle and was even alleged to have killed the Shawnee chief Tecumseh. Johnson was a national hero.

Johnson was not a one-dimensional soldier. According to the Kentucky Encyclopedia, Johnson was a devout Baptist who supported education. He established the Choctaw Academy at his Blue Spring farm near Great Crossing in 1820s.

Richard Mentor Johnson founded the Choctaw Academy in 1825, near Stamping Ground in Scott County. It was intended to educate American Indian youth. It was one of the first inter-racial schools in America, and it closed in 1845. There were also several white families who sent their sons.

The Choctaw, along with many other tribes, sent their boys to study writing, reading, grammar, geography and practical surveying.

Enrollment was close to 200 by 1835. Johnson was described by a Choctaw chief as having a noble impulse, big heart and a strong will to succeed.

The school was still closed in 1840. The Choctaw were expelled to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), where the Kentucky academy was supplanted with mission schools.

Choctaw Academy students were successful in business and politics. Some students found it difficult to go back to their tribes because they lost touch with their Native American culture and relatives.

According to the website Kentucky Historic Institutions, many of these young men were unable to adapt to the changes and would commit suicide.

Continue the story

Johnson's unusual relationship with Julia Chinn was more remarkable and shocking to his contemporaries. She was an enslaved girl who was given to Johnson as part his fathers estate.

Many white men were involved in sexual relationships with enslaved females. Thomas Jefferson is an example. These relationships were essentially rape.

Johnson however did not hide or deny his actions like other white men. He openly lived with Chinn and declared her his wife. Although antebellum laws against mixed race marriages prevented their union from being legalized, he still married her. Their common-law marriage lasted for two decades.

Chinn wore the most elegant fashions as a wife to a wealthy man and hosted Johnson's parties at Blue Spring plantation. The Washington Post reported that the couple hosted the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825.

Johnson was absent for long periods to Washington, D.C., so Chinn managed his plantation of 2,000 acres. Johnson instructed his white employees to treat her and his absence as a sign of respect. She was also the Choctaw Academy's medical ward.

They had two daughters, Adaline and Imogene. Johnson gave them their last names. Johnson insisted that they be accepted as white children by the society.

According to the Lexington Observer, Adaline was not allowed to sit in the pavilion with prominent White citizens when Johnson spoke at a local July 4 celebration. Johnson drove his daughter to the carriage with him, then rushed through his speech before driving off furiously.

Chinn was cholera-related and died in 1833. Johnson did not emancipate her for reasons I have not seen. Johnson may have loved her, and considered her his wife. However, she was legally enslaved until her passing.

Johnson's political enemies mocked him for his interracial marriage and his children.

His brothers destroyed Johnson's papers 17 years after Chinn died to prevent his surviving daughter Imogene from inheriting his estate. They may have wanted to keep the history of Johnson's and Chinns marriage secret.

Amrita Chakrabarti, an Indiana University professor, has written a book on Chinn, The Vice Presidents Black Wife. It is scheduled to be published in the University of North Carolina Press.

Myers contrasts the attention paid to Henry Clay, another Kentuckian from the same period, with Johnson's relative obscurity.

She wrote that the whole thing was depressing in an essay online. Johnsons Blue Spring Farm's main house is gone. The cemeteries are overgrown and have vanished to the naked eye. And the last school building on the property is in danger of falling into the ground.

Nearby Lexington hosts thousands of tourists each year who visit the beautifully maintained gardens and halls at Ashland, home to Henry Clay, Kentucky's other great antebellum statesman. It is impossible to imagine the contrast between these two places. The reason for the differences is rooted in race.

Johnson and Chinn are the reason I enjoy history research and reading. It is clear that human beings are always complex, contradictory, and often surprising. Complex times have always existed.

Paul Prather pastors Bethesda Church in Mount Sterling. You can reach him at pratpd@yahoo.com.