Researchers have been gathering important and new insights about the effects of COVID-19 in brain and body for more than 18 months. These findings raise concerns about the potential long-term effects of the coronavirus on biological processes, such as aging.

My past research as a cognitive neuroscientist has been focused on understanding how brain changes due to aging impact people's ability think and move, especially in middle age.

My research team began to be interested in how COVID-19 might affect natural aging as we received more evidence.

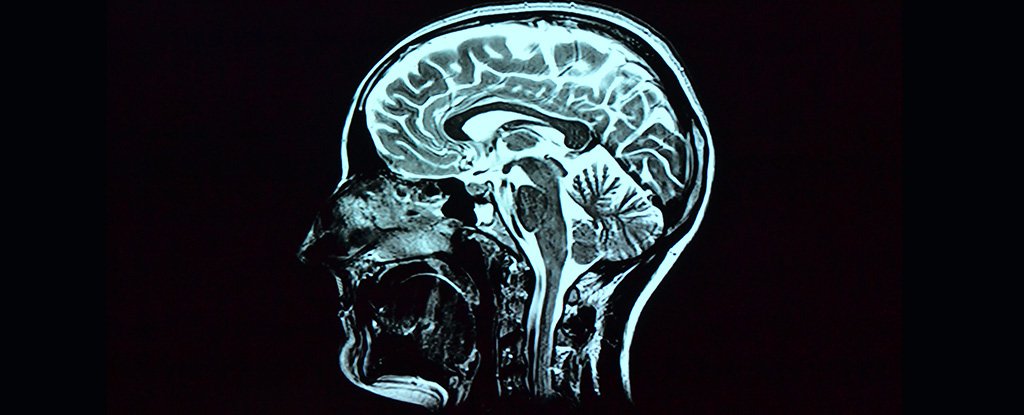

Observing the brain's reaction to COVID-19

A preliminary, but large-scale study that examined brain changes in COVID-19 patients was published in August 2021. It attracted a lot of attention from the neuroscience community.

Researchers used data from the UK Biobank to conduct the study. This database contains brain imaging data for over 45,000 UK citizens dating back to 2014. This is crucial because there were baseline data and brain imaging for all those people who lived before the pandemic.

After analysing the brain imaging data, the research team brought back people who had been diagnosed as having COVID-19 to have additional brain scans. The researchers compared participants who had COVID-19 with those who hadn't. They carefully matched the groups based upon age, sex and study location as well as other risk factors such as socioeconomic status and health variables.

Researchers found significant differences in gray matter between people who were infected by COVID-19 and others who weren't. This is composed of cells that are responsible for processing information in the brain.

The COVID-19 group showed a reduction in gray matter thickness in brain regions called the frontal and temporal, which was different from the usual patterns in those who hadn't been exposed to COVID-19.

It is common for gray matter thickness to change over time in the general population. However, the changes in COVID-19 infected patients showed greater than normal changes.

The results of the research showed that patients with severe COVID-19 were not separated from those who needed hospitalization. This means that people infected by COVID-19 had brain volume loss even though the disease wasn't severe enough to warrant hospitalization.

Researchers also looked at cognitive performance and discovered that people with COVID-19 performed slower on information processing tasks than those without.

Although we need to be cautious in how these findings are interpreted as they await formal peer reviews, the large sample of pre- and post-illness data from the same people, and careful matching with people without COVID-19 make this preliminary work especially valuable.

What does this mean for brain volume?

The loss of senses of taste and smell was a common complaint from COVID-19 infected people early in the pandemic.

Surprisingly, the brain areas that were impacted by COVID-19 in the UK are all connected to the olfactory bulbs, which is a structure located near the front of brain that transmits signals about smells from the nose and other brain regions. There are connections between the olfactory bulbs and regions of the temporal-lobe.

The hippocampus is found in the temporal lobe, which is why we often refer to it when discussing aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Given its role in cognitive and memory processes, the hippocampus will likely play a significant role in aging.

Research on Alzheimer's disease is important because some data suggests that people at high risk have a diminished sense of smell.

Although it is too early to draw conclusions about the long-term effects of these COVID-19-related changes on memory, the investigation of possible connections between COVID-19 brain changes and memory is very interesting due to the importance of the regions involved in memory and Alzheimer’s disease.

Looking ahead

These findings raise important questions that remain unanswered. Is the brain able to recover from viral infection over time?

These are open and active areas of research that we are starting to do in our laboratory, in addition to our ongoing work on brain aging.

Our research shows that the brain processes and thinks differently as we age. We also observed changes in the way people move and learn new motor skills over time.

Research over many decades has shown that older adults have difficulty processing and manipulating information, such as updating a grocery list. However, they still retain their vocabulary and knowledge of facts. Motor skills are another area where we know older adults learn slower than young adults.

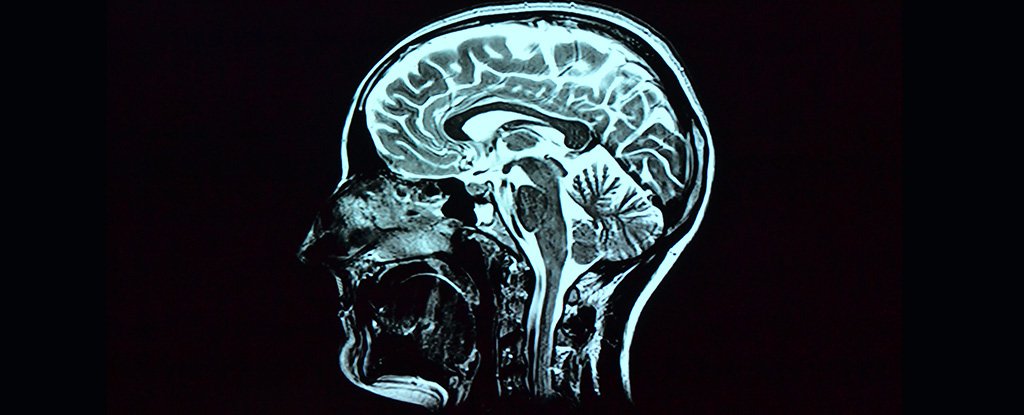

Adults over 65 experience a decline in brain size. This decline is not limited to one region. There are differences across the brain. Due to the loss in brain tissue, there is often an increase of cerebrospinal liquid that fills spaces.

White matter is not only less intact in older people, but so is the insulation on long cables called axons that transmit electrical impulses between nerve cell.

In the last decade, life expectancy has increased and more people are getting older. Although everyone wants to live long, healthy lives, it is not possible for everyone to age without any disability or disease. However, the older years can bring about changes in our thinking and movement.

Understanding how these pieces fit together will allow us to unravel the mysteries surrounding aging and help people with aging improve their quality of life. It will also help us to understand how the brain might recover from illness in the context COVID-19.

Jessica Bernard, Associate Professor, Texas A&M University.

This article was republished by The Conversation under Creative Commons. You can read the original article.