Over the years, hospitals and doctors have seen kidney patients differently depending on their race. An equation to estimate kidney function used a correction for Black patients. This made their health look better, which prevented them from receiving transplants.

Two of the most respected kidney care organizations formed a task force on Thursday to say that this practice was unfair and must be stopped.

This group was a collaboration of the American Society of Nephrology and the National Kidney Foundation. It recommended a new formula that doesn't factor in the patient's race. Paul Palevsky (the president of the foundations) issued a statement urging all health care systems and laboratories to adopt this new approach quickly. This is important because professional medical societies have a significant influence on how patients are cared for.

In 2020, a study that examined records from 57,000 Massachusetts residents found that one third of Black patients would have their disease classified as more serious if they were assessed using the same formula as white patients. One example of a group of medical algorithms and calculators that has recently been criticized for conditioning patient care based upon race was the traditional kidney calculation. This is a social category, not a biological one.

Last year's review listed over a dozen of these tools in areas like cardiology and cancer care. This led to a surge in activism by a variety of groups, including medical students and lawmakers like Senator Elizabeth Warren (D.Massachusetts), and Richard Neal (D.Massachusetts), who were both against the practice.

There are signs that the tide is changing recently. After student protests, the University of Washington decided to stop using race in kidney calculations. In 2020, Vanderbilt and Mass General Brigham hospitals also stopped using the practice.

Advertisement

A tool that used to predict whether a woman could have a safe vaginal birth after a previous cesarean was updated in May to not automatically give lower scores to Hispanic and Black women. The calculator that calculates the likelihood of a child getting a urinary tract infection in her child was updated to not reduce the scores for Black patients.

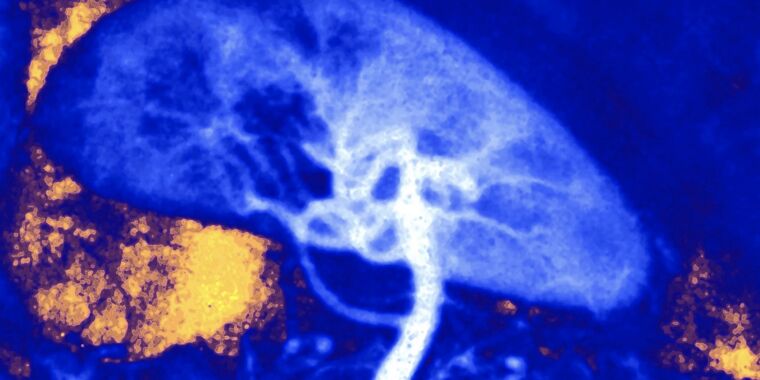

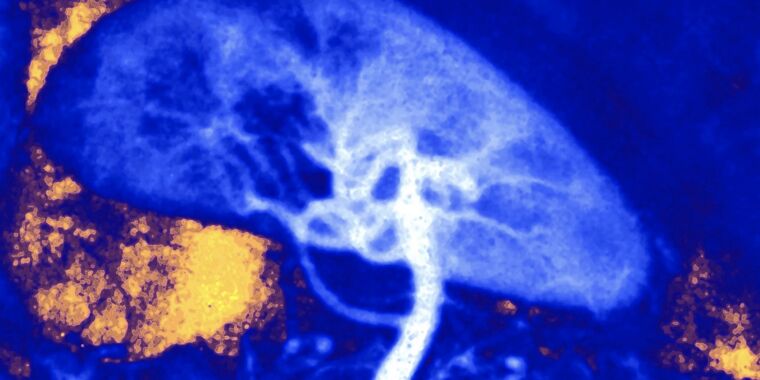

In 2009, CKD-EPI was created to replace a 1999 formula which used race as a method of assessing kidney disease. It converts creatinine levels in blood into an estimate of kidney function, called estimated glomerular filter rate (eGFR). Doctors use the eGFR to classify a person's illness and determine whether they are eligible for treatment, such as transplants. Higher scores are achieved by healthy kidneys.

The equations design included a person's age and sex, but also increased the score for any patient who was Black by 15.9%. This feature was added to account for statistical patterns in patient data that were used to inform the design CKD-EPI. These patients included a small number of people of Black origin or other racial groups. However, it allowed a person's perceived race to change how their disease was treated or measured. For example, a person of mixed heritage could have their illness classified differently by the health system depending on how they were seen by their doctor or their identification.

NwamakaEneanya, an assistant professor from University of Pennsylvania, was a member of Thursday's task force. She said she knew of one patient with severe kidney disease, who, after learning more about the equation, requested that she be considered white in order to improve her chances of receiving advanced care. Eneanya believes that a change from the current equation is long overdue. It is completely wrong to use someone's skin color as a guide for their medical treatment.

Eneanya was coauthor of the 2020 study about the possible impact of race in the kidney function equation. The study found 64 cases in which a Black person's score could have been recalculated using the same method used for white patients to qualify them for the kidney transplant waiting list. All of these patients were not evaluated for transplantation, which suggests that doctors did not question their race-based recommendations.

Advertisement

The New England Journal of Medicine published a revised version of the equation on Thursday. It does not consider race and was created using a wider range of data than the original eGFR equation. It should yield better results for different populations than the existing equation for non-Black patients. A second method for estimating kidney function, which is based on a lesser-known blood test for compound cystatin C, could be more accurate in different populations.

Researchers are still unsure if the kidney society's approach is the best. Researchers from Stanford, Kaiser Permanente and UC San Francisco published a paper in The New England Journal that concluded that creatinine levels were not a reliable way to assess kidney function. They also suggested that cystatin C-based equations be used.

Updates to the equation used by a health care provider in nephrology are relatively easy. They require only minor changes to an electronic health records system. It is harder to change an established tradition of health care. Thursday's recommendations were based on the belief that some patients might need to be reassessed and that new guidelines and educational material are necessary for both doctors and patients.

Vanessa Grubbs, who is a nephrologist and co-authored a petition calling on the kidney societies to take action, was happy with Thursday's news, but noted that it had been decades in the making. She hopes her specialty will shift to the more precise, but less well-established cystatin C test. However, she also wants to address the wider issues that are being raised in the kidney calculation debate.

Grubbs believes that there must be a racial reckoning in medicine. It is still a problem to try and inject biological meaning into races, particularly Black races.

The American Medical Association made a similar statement in May when it announced a plan to promote health equity that is based on racial justice. The document stated that racism, exclusion, oppression, and violence harm and kill and deprive our society of its full potential, especially in the areas of health. The document cited issues such as low diversity in doctors, lack of research on health disparities and the use race in clinical tools.

This story first appeared on wired.com