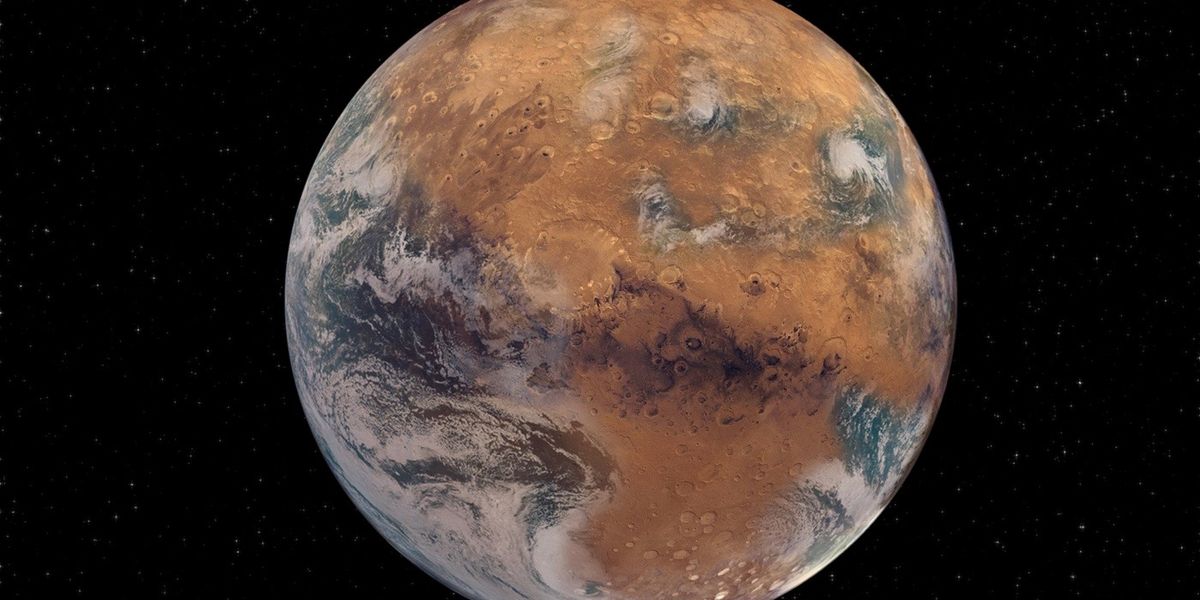

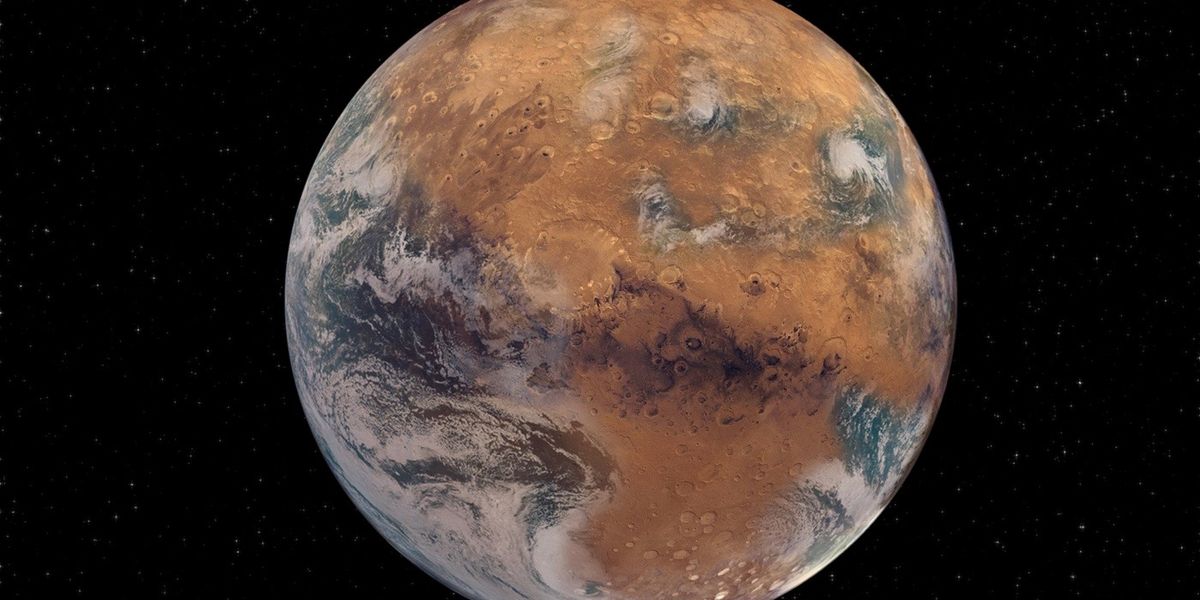

A new study has shown that Mars' small size was a sign of its doom to dehydration.

Scientists have discovered that liquid water once ran across the Martian surface thanks to the observations of robotic explorers like NASA's Curiosity or Perseverance rovers. The Red Planet may have had streams, lakes, rivers, and maybe even an ocean that covered large swathes of its northern hemisphere.

However, that surface water disappeared along with most of the Martian atmosphere around 3.5 billion years ago. Scientists believe that this dramatic climate shift was caused by the loss of the Red Planet's global magnetic field. This had prevented Mars' atmosphere from being destroyed by charged particles from the sun.

Similar: Photos of the search for water on Mars

According to the new study, this proximate cause was actually underpinned by a more fundamental driver: Mars is too small to retain surface water for the long-term.

Kun Wang, a Washington University assistant professor in Earth and planetary sciences, stated that Mars' fate was determined from the beginning. There is likely to be a threshold for rocky planets that must retain sufficient water to allow them to support habitability and plate-tectonics. Scientists believe that this threshold is higher than Mars.

Zhen Tian, a graduate student in Wang’s lab, led the study team. They examined 20 Mars meteorites and selected them to represent the Red Planet's bulk. These extraterrestrial rocks ranged in their age from 200million years to four billion. The researchers determined the abundances of different isotopes potassium. (Isotopes refer to versions of an element that have different numbers of neutrons within their atomic nuclei.

Tian and her coworkers used potassium (the chemical symbol K) as a tracer to more volatile elements and compounds. This is stuff like water which can transition to the gas phase at low temperatures. Mars was nine times larger than Earth and lost more volatiles in its formation than Earth. Mars retained its volatiles much better than Earth's moon (329 miles) and Vesta (530 km), both smaller and dryer than the Red Planet.

Katharina Lodders from Washington University is a co-author. She stated that the reason for much lower levels of volatile elements and compounds on differentiated planets than primitive undifferentiated meteorites was a long-standing question. "Differentiated" is a cosmic body that has its interior divided into various layers such as the crust, core, and mantle.

Lodders stated that the discovery of the correlation between K isotopic compositions and planet gravity was a new discovery that has important quantitative implications for when and where the volatiles of differentiated planets were received.

The latest study was published online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences on Sept. 20, and together with previous work suggests that small sizes are a double win for habitability. Bantam planets are known to lose a lot of water in formation. Their global magnetic fields also fail early, leading to atmospheric thinning. (In contrast, the Earth's magnetic field remains strong and is powered by a dynamo deep inside our planet.

Team members stated that the new work could also have applications outside of our cosmic backyard.

Klaus Mezger from the University of Bern, co-author of the study, stated in the same statement that "This study highlights that there is only a very limited range for planets in which they can have just enough water but not too much to develop a habitable environment." These results will help astronomers to search for habitable exoplanets within other solar systems.

The "surface environment" disclaimer in any discussion about habitability is important. Scientists believe that Mars may still support underground aquifers capable of supporting life. Moons like Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus may also have huge oceans that could support life beneath their ice-covered surface.

Mike Wall is the author and illustrator of "Out There" by Grand Central Publishing (2018). This book is about the search for alien life. Follow him @michaeldwall. Follow us on Facebook @Spacedotcom and Twitter @michaeldwall