Around 200,000 years ago, children from the Ice Age squished their feet and hands into sticky mud at thousands of feet up on the Tibetan Plateau. These impressions are preserved in limestone and could be the oldest evidence of human ancestors living in the area.

The study authors claim that the footprints and hand should be considered "parietal art", which is prehistoric art that can't be moved from one place to another. This usually refers, for example, to petroglyphs or paintings on cave walls. An expert said that not all archaeologists agree that the prints found in the new discovery are parietal art.

Ice age children left behind traces

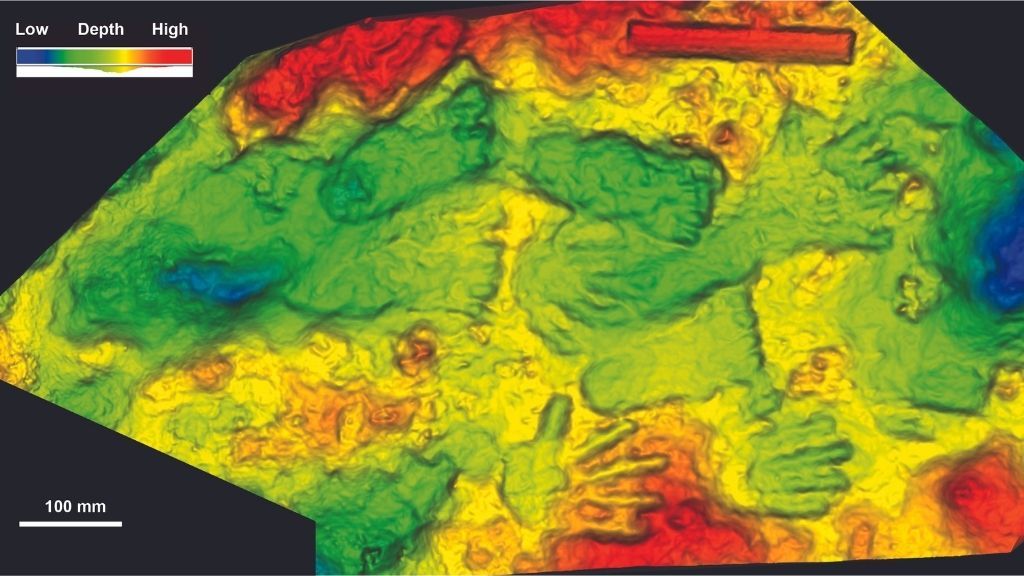

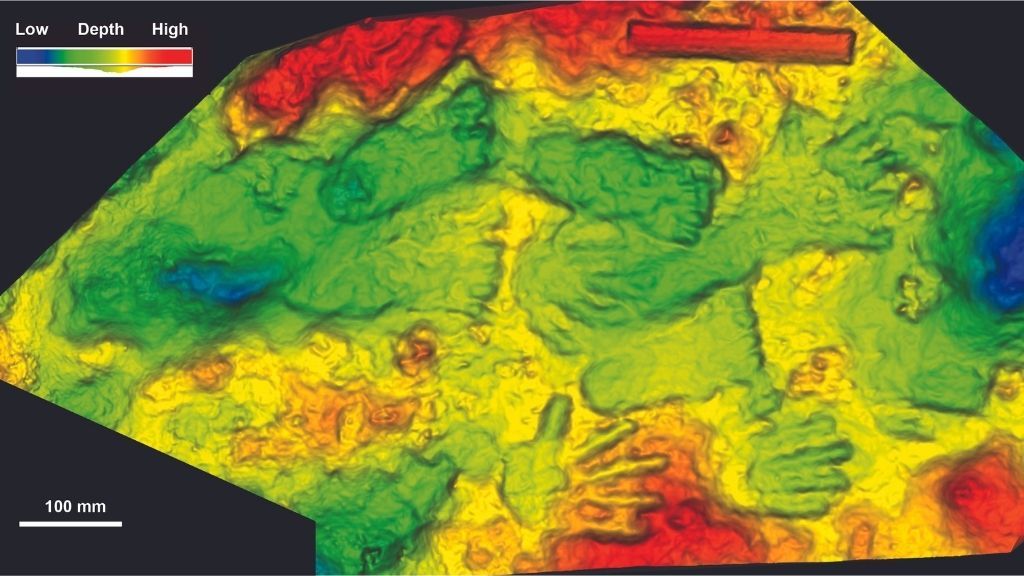

David Zhang, a professor at Guangzhou University, China, was the study author. He first noticed the five handprints, and five footprints while on an expedition to Quesang, a fossil hotspring at Quesang. Quesang is located at more than 13,100 feet (4,00 meters) above the sea level on Tibet's Plateau. The authors used radioactive elements found naturally in the environment to date the sample. They calculated that the impressions were made between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago, based on the rate at which the uranium is lost. This was right in the middle the Pleistocene Epoch, which took place 2.6 million to 11.700 years ago.

Similar: Photos: Searching for extinct people in ancient cave mud

The team found that the marks were left behind by two children. One was about the same size as a 7-year old and the other was 12 years old. Matthew Bennett, co-author of the study and a professor in environmental and geographic sciences at Bournemouth University, Poole, England, stated that the team cannot be certain what archaic human species left the prints.

Bennett said that Denisovans were a possibility, but Homo Erectus was also known in the area, referring to some of our human ancestors. There are many contenders but we don't know the truth.

Bennett said that the prints provide the earliest evidence of hominins in Quesang. However, there is increasing evidence that archaic people were present on the Tibetan Plateau around the same time. For example, scientists have recently found a Denisovan jawbone within the Baishiya Cave. This cave is located at the northeastern border of the Tibetan Plateau. Emmanuelle Honor was not involved in this study. Honor explained to Live Science via email that the mandible is at least 160,000 years old. This means the bone remnants could be from the same time period as the Quesang handprints.

However, the Baishiya Cave is located many miles north of Quesang at a height of only 10,500 feet (3.200 m) above the sea level. The newfound handprints provide the oldest evidence of occupation in this region of the plateau. Michael Meyer, an assistant professor of geoology at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, was not part of the study. Meyer believes that Denisovans left the handprints. He told Live Science via email that the study could indicate that Denisovans were first Tibetans and that their genetic adaptations to high-elevation stress may have been a result of this.

Travertine is a type of freshwater limestone that has been formed from mineral deposits in natural springs. The handprints are made of it. Bennett explained that travertine is a fine, slippery mud when it's first deposited. It can be pushed into with one's hands or feet. When the water is removed, travertine becomes stone.

(Image credit: Gabriel Ugeto's artwork, provided by Matthew Bennett.

Zhang found similar footprints and hand prints on a 1980s expedition. There are also many signs of human activity on the nearby slopes. The size of the previously discovered foot and hand impressions is variable, which suggests that they were left by both children and adults. However, they seem to have been created organically by people as they moved across the land. Bennett stated that the new prints are different in that they seem to have been deliberately left.

He said, "They are deliberately placed... You wouldn't necessarily get those traces if your normal activities were across the slope." They are actually placed within the space as though someone was making a more deliberate arrangement. Bennett said that the prints were similar to finger flutings, a type of prehistoric art where people ran their fingers across soft surfaces on cave walls. Bennett stated that both children and adults may have taken part in finger fluting.

Similar: 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Bennett stated that Bennett is comparing modern times to his 3-year-old daughter. "When she does a sketch, I put it on my fridge and label it art. While an art critic might not necessarily consider my child's scribbles art, they would in general usage. This is also true.

Some footprints and hand prints are preserved in limestone at the Tibetan Plateau. (Image credit: Matthew Bennett

Art work?

The authors pointed out that the Quesang prints could be considered parietal art if they are. Hand motifs and stencils from the Indonesian island Sulawesi, as well as El Castillo cave, in Spain, were the oldest examples of parietal artwork. They are both approximately 45,000 to 40,000 years old.

Related: Photos: The oldest cave art in the world

Honor explained that Quesang had little to do with the two sites except that they all display hand footprints. "Leaving a mark in the mud or making a stencil with pigments is quite a different process from both a technical and conceptual standpoint."

Honor believes that parietal art is anything but paintings and engravings made from rock. However, Honor and other archaeologists would disagree with this view. Honor stated that finger fluting is a subject where some people consider it art, while others see it as pre-art, or as an experiment [or] play." Honor said, "I personally would be in this last group of researchers."

Meyer stated that "classifying these human traces in art is something that is only secondary to my opinion." The study's most important implications are that the Tibetan Plateau was occupied by human ancestors much earlier than previously believed. This raises questions about the origins of the prints and the route they traveled to reach the plateau. Meyer expressed his hope that future studies will confirm the age of imprints and explain how they have remained so preserved over time.

Honor stated that no matter how the prints are defined by contemporary scholars, it is important to remember that "what we consider art was probably not viewed the same way by the people who made it." We may never find out what the ancient hominin children were doing when they put their feet on the hillside. Nor can we know what their older kin thought of their efforts. Bennett considers the fossilized remains of two children playing with the mud to be art.

Original publication on Live Science