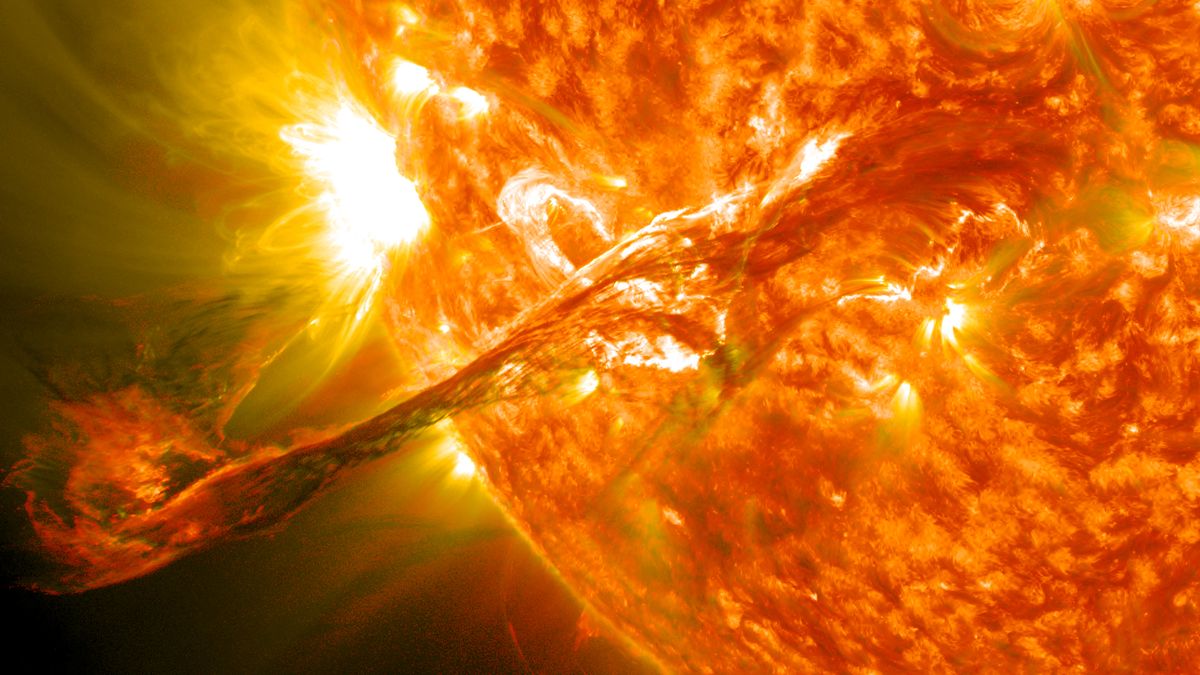

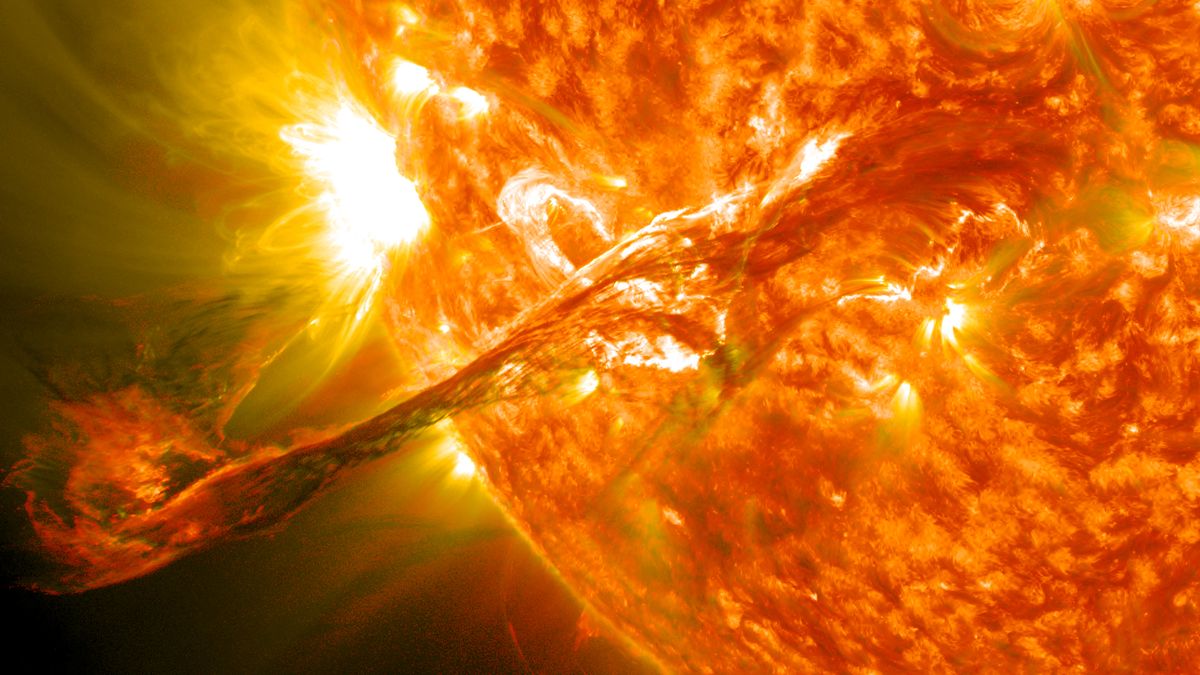

The sun constantly showers Earth with a mist made of magnetized particles called solar wind. Our planet's magnetic shield prevents this electric wind from doing any damage to Earth or its inhabitants. Instead, they send those particles skittering towards the poles, leaving behind a pleasant aurora.

Sometimes, however, this wind can become a full-blown sunspot every century. This is according to new research presented at SIGCOMM 2021 data communication conference. It could lead to a complete disruption in our modern way of living.

According to the new research paper, Sangeetha Abdul Jyothi, an assistant professor from the University of California Irvine, said that a severe solar storm could cause the world to experience an "internet apocalypse", which can keep large sections of society offline for several weeks or months. The paper is still to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

"What really got my attention was that we saw the unpreparedness of the world during the pandemic. WIRED's Abdu Jyothi said that there was no effective protocol for dealing with the pandemic. "Our infrastructure isn't ready for large-scale solar events."

One problem is that extreme solar storms, also known as coronal mass ejections, are very rare. According to Abdu Jyothi’s paper, scientists estimate that the likelihood of an extreme space weather directly affecting Earth at 1.6% to 12.6% per decade.

Only two of these storms have been documented in recent history: one in 1859, and one in 1921. Carrington Event - the earlier incident that caused such a severe geomagnetic disruption on Earth, telegraph wires burst in flame and auroras normally only visible near the planets poles were spotted close to equatorial Colombia. Even smaller storms can pack a punch. A March 1989 storm blacked out Quebec, Canada for nine hours.

Abdu Jyothi stated that human civilization has grown more dependent on the internet and that the potential effects of a large geomagnetic storm upon this new infrastructure have not been studied. She attempted to identify the most vulnerable parts of that infrastructure in her new paper.

According to the paper, the good news is that local and regional internet connections are unlikely to be damaged by geomagnetically-induced currents.

The long undersea cables connecting continents to the internet are an entirely different story. These cables have repeaters that boost the optical signal. They are located at intervals of approximately 30 to 90 miles (50-150 kilometers). According to the paper, these repeaters can be affected by geomagnetic currents and whole cables could become useless if one repeater is lost.

Abdu Jyothi stated that if enough cables are damaged in one region, entire continents may be separated. Additionally, countries at higher latitudes like the U.S.A. and the U.K. are more vulnerable to solar storms than those at lower latitudes. High-latitude countries are more likely to lose their internet connection in the event of a severe geomagnetic storm. Although it is difficult to predict the time required to fix underwater infrastructure, Abdu Jyothi believes that outages of large scale that can last several weeks or even months may be possible.

Millions of people could lose their jobs in the interim.

Abdu Jyothi stated in her paper that the economic impact of an Internet interruption for one day in the US was estimated at more than $7 billion. "What happens if the network is not functional for days, weeks, or even months?"

Grid operators must start to take the risk of extreme solar storms seriously, as the global internet infrastructure expands. Abdu Jyothi stated that laying more cables at lower latitudes would be a good place to start. He also suggested that resilience tests should be developed that examine the impact of large-scale network breakdowns.

She said that the Earth will have 13 hours to prepare for the next solar storm when it does strike our star. Let's all hope that we are ready to take advantage of the time it takes to arrive.

Original publication on Live Science