This article was first published by The Conversation. Space.com's Expert voices: Op-Ed and Insights was contributed by the publication.

David Rothery, Professor in Planetary Geosciences at The Open University

We often think of only Earth's amazing geological features when we talk about them. As a geologist, it's absurd to think there are so many structures elsewhere that could excite and inspire. This can help us see the processes happening on our planet.

These are, in no particular order (except Earth), the five most impressive geological structures of the solar system.

The most majestic canyon

Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system, was left out to include Valles Marineris, that planet's most stunning canyon. This canyon is a stunning sight from space, measuring 3,000 km in length, hundreds of kilometers in width, and eight kilometers deep. If you could stand on one of the rims, the other rim would be well beyond the horizon.

Valles Marineris as seen from 5,000km above the surface in a colour-coded topographic image (left). Imaged by Esas Mars Express' High Resolution Stereo Camera (right). Google Earth and NASA/USGS/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum).

It was likely caused by the fracturing of a nearby volcanic region (called Tharsis), but it was widening and deepened by a series catastrophic floods that climaxed over 3 billion years ago.

Continue reading: Plate tectonics: New findings complete the 50-year-old theory explaining Earth's landmasses

Venus' mountains are folded

Two NASA missions and one ESA mission (European Space Agency), will bring us more information about Venus in 2030s. Venus is almost the same size, weight, and density as Earth. This has caused geologists to wonder why Venus lacks Earth-like plate tectonics, and why (or even whether) it has relatively little active volcanism. How does it get its heat?

Fold mountains in Ovda Regio (Venus). This insert shows a similar view to central Pennsylvania's Applachians. Image credit NASA/JPL

It is comforting to know that at least some aspects Venus' geology are similar. The Ovda Regio northern margin looks very similar to the Ovda Regio highlands. However, there are no rivers that cut through the fold-like pattern. This allows for "fold mountains" on Earth like the Appalachians which result from a collision of continents.

Blasted Mercury

My next example is a bit of cheating, as it contains both the largest solar system impact basins and an explosive volcano. Mercury's Caloris basin, measuring 1,550 kilometers in diameter, was formed about 3.5 billion year ago by an asteroid impact. Soon afterward, its floor was flooded with lavas.

A series of explosive eruptions caused kilometers-deep cracks in the solidified lavas at the edge of the basin, where the lava caps was the thinnest. These volcanic ash particles were sprayed out across a distance of tens to hundreds of kilometers. Agwo Facula is one such deposit that surrounds the explosive vent I chose as an example.

Right: Most of Mercurys Caloris basin is covered in orange lava. Explosive eruptions leave behind brighter patches of orange lava. Below: Close-up of the red box containing an explosive volcanic deposit. Upper left: Details of the vent interior. (Image credit NASA/JHUAPL/CIW

Explosive eruptions are caused by expanding gas and are surprising to find on Mercury. Mercury's proximity to the sun had been expected to have rendered it devoid of volatile substances that would have caused them to boil off. Scientists believe there were multiple explosive eruptions that occurred over a long time period. Mercury's magmas were repeatedly stocked with gas-forming volatile substances (whose composition is still unknown until ESA's BepiColombo mission begins work in 2026).

The highest cliff in the world?

Cliffs are the best places to find clean rock in soil- or vegetation-rich areas. They are dangerous to approach but they offer a continuous cross-section of rocks and can be used for fossil hunting. Geologists love them so I present the Verona Rupes, seven-kilometers high. This feature is located on Uranus' small moon Miranda and is frequently called "the tallest rock in the solar system," according to a NASA website. It would take 12 minutes to fall from the top if you were to slip and fall off the top.

Verona Rupes is approximately 50km long by several kilometers high. However, it's not as cliff-like than Voyager 2 saw during its 1986 flyby. Image credit: NASA/JPL

Read more: Mercury's mysterious red spots get named, but what are they?

Verona Rupes's verticality is absurd. It is only visible in Voyager 2 images, taken during the 1986 flyby of Uranus. It is undoubtedly impressive. It appears to be a geological fault, where one block of Miranda’s icy crust (the outermost shell) of the planet has moved down against the adjacent block.

The view is oblique, so it's difficult to see the steepness. It probably slopes at 45 degrees. It's unlikely that you would slip if you fell at the top. Although the face appears very smooth, it is difficult to see in the best, low-resolution image we have. However, Mirandas -170C daytime temperatures means that water-ice has high friction and is not slippery.

Titan drowns the coast

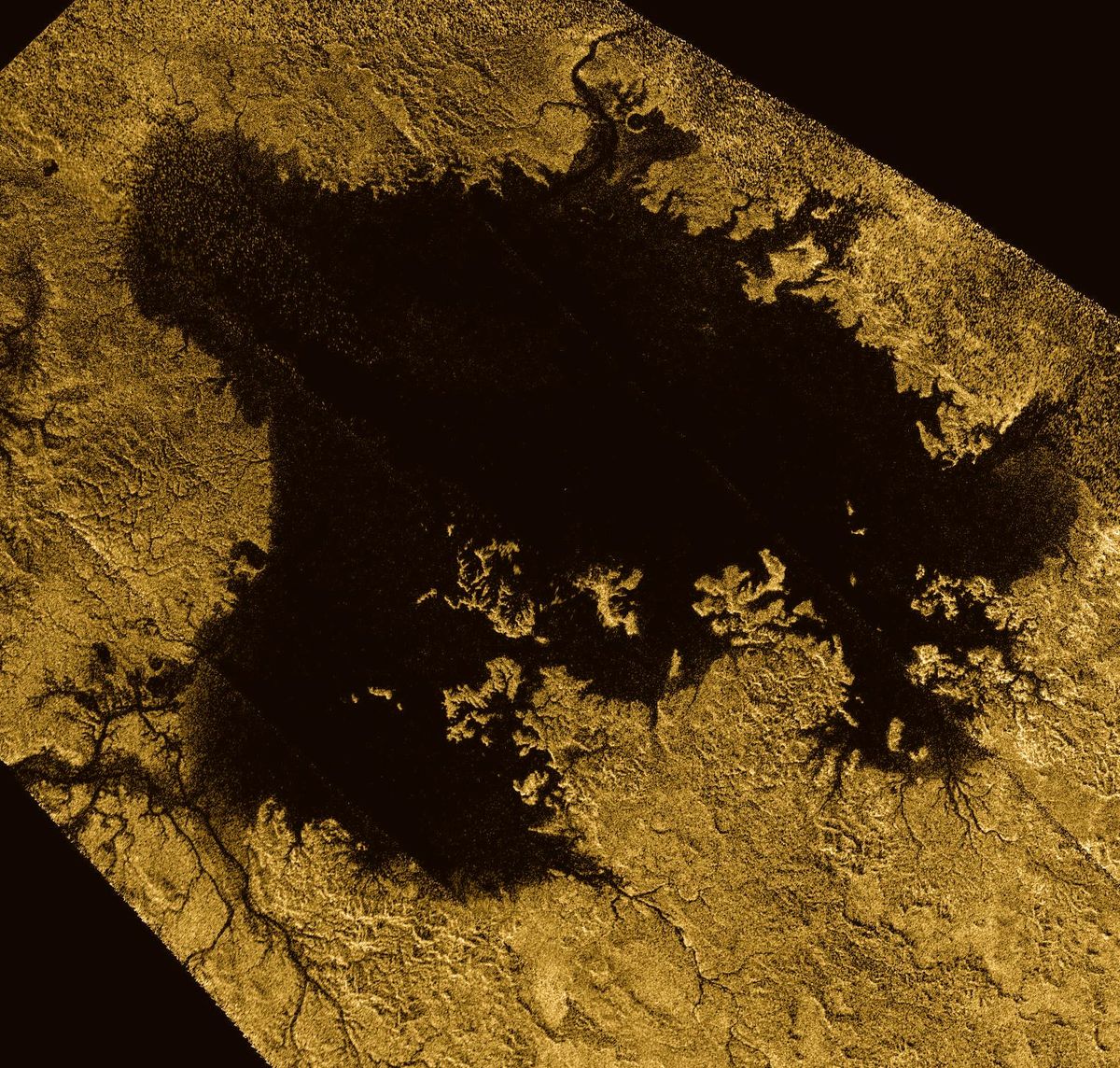

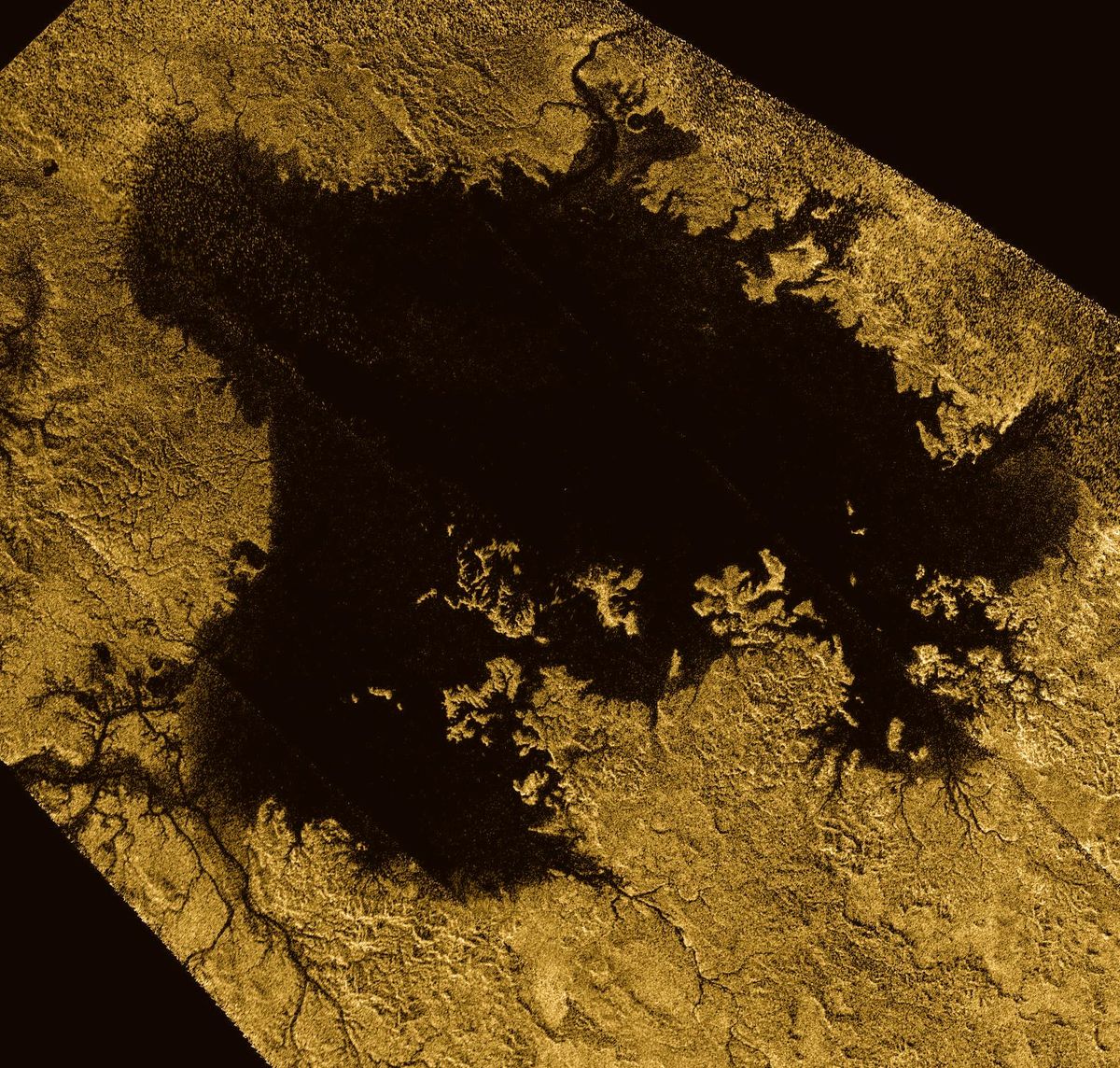

My final example could have been anywhere on Pluto. But instead, I chose a hauntingly Earth-like coastline, on Saturn's largest moon Titan. A large depression in Titan’s water-ice "bedrock” hosts a sea liquid methane called Ligeia Mare.

Valleys formed by methane rivers that flow into the sea have clearly been flooded with seawater. This coastline is very similar to Oman's Musandam Peninsula, which lies south of the Straits of Hormuz. The ongoing collision of Asian and Arabian mainlands has caused the local crust to shift downwards. Is there a similar event on Titan? Although we don't yet know the answer, the changes in coastal geomorphology around Ligeia Mare suggest that these drowned valleys are not just a result of rising liquid levels.

Left: A part of Titans Ligeia Mare showing a coastline that has valleys submerged in a sea liquid methane. Right: The Musandam Peninsula, Arabia, where the coastal valleys are similarly drowned by a sea of liquid methane. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell and Expedition 63, International Space Station (ISS))

Continue reading: Titan: The first global map reveals the secrets of a potential habitable moon of Saturn

It doesn't matter if you have liquid water or rock on Earth. On Titan, liquid methane and frigid water-ice are the same. They interact in the same way, so geology is repeating itself on other worlds.

This article was republished by The Conversation under Creative Commons. You can read the original article.

Follow Expert Voices to keep up with the debates and issues. You can also join the conversation on Facebook and Twitter. These views are the author's and may not reflect those of the publisher.