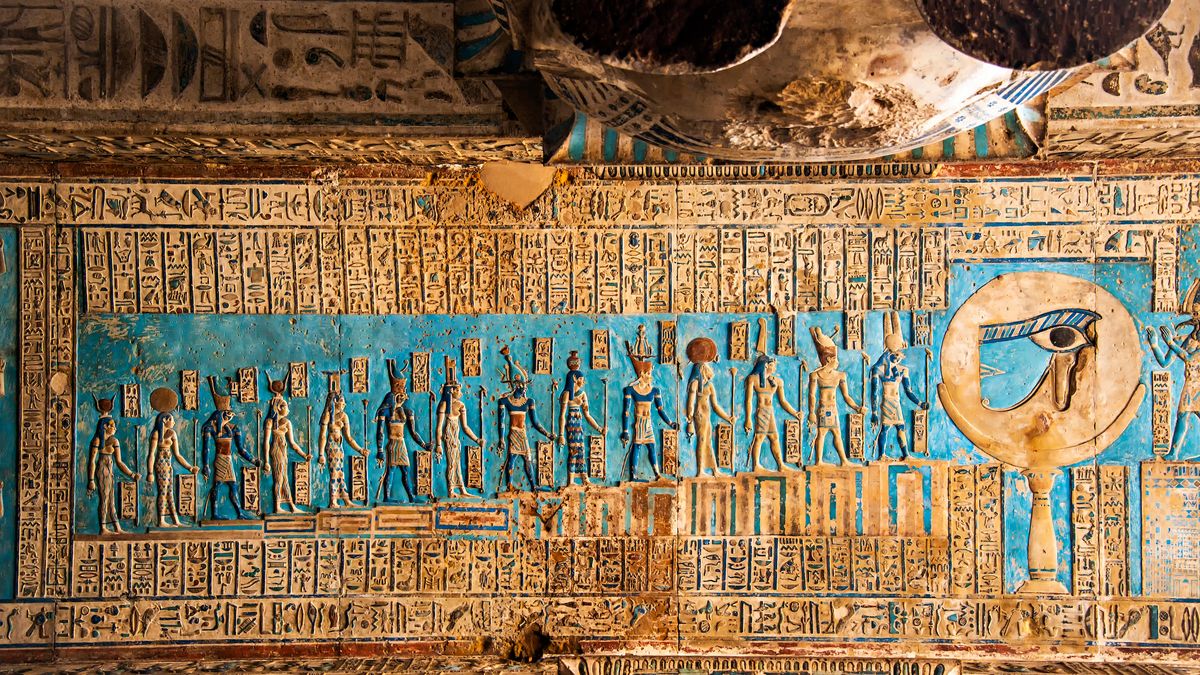

Hieroglyphs from Ancient Egypt on the ceiling of Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Hathor, Egypt. (Image credit to Paul Biris via Getty Images

Although some ancient societies used written languages, deciphering these texts can prove difficult. How can experts translate ancient words into modern languages?

There are many ways to answer this question, but one example is a classic: The decoding of Rosetta stone, which was discovered in Egypt by a French military expedition in July 1799. This discovery helped pave the path for the decipherment and interpretation of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The stone holds a decree of Ptolemy VI that was inscribed in three writing systems: Egyptian hieroglyphics and demotic script (used between the seventh and seventh centuries B.C. The fifth century A.D. and ancient Greek. The decree was written in 196 B.C. and stated that Egyptian priests had agreed to crown Ptolemy VI pharaoh in return for tax breaks. Egypt was then governed by a dynasty consisting of Ptolemy I (one of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian generals).

Related: What if Alexander The Great gave his empire to just one person?

Both hieroglyphics as well as demotic script were unintelligible at the time of the stone's discovery. However, ancient Greek was already known. Because the same decree was preserved by three languages, scholars were able to read it in Greek and then compare it with the hieroglyphics and demotic portions to find the equivalent.

The Rosetta inscription is now the symbol of decipherment. It implies that bilinguals are the most important tool for decipherment. Notice this: Although copies of the Rosetta inscription have been circulated among scholars since its discovery, it would be more than 20 years before any significant progress was made in decipherment." Andras Stauder from cole Pratique des Hautes tudes, Paris, explained to Live Science via email.

James Allen, an Egyptology professor at Brown University, said that hieroglyphic writing includes signs that can represent sounds and other signs which can represent ideas (like the way people use a heart sign today to show love). Jean-Franois Champollion (1790-1832), a scholar who began studying hieroglyphs in 1790-1832, was the only one to believe that hieroglyphs could be symbolic. Allen explained this to Live Science via email that scholars had believed that hieroglyphs were only symbolic. Champollion's greatest contribution was to recognize that hieroglyphs could also be used for sounds.

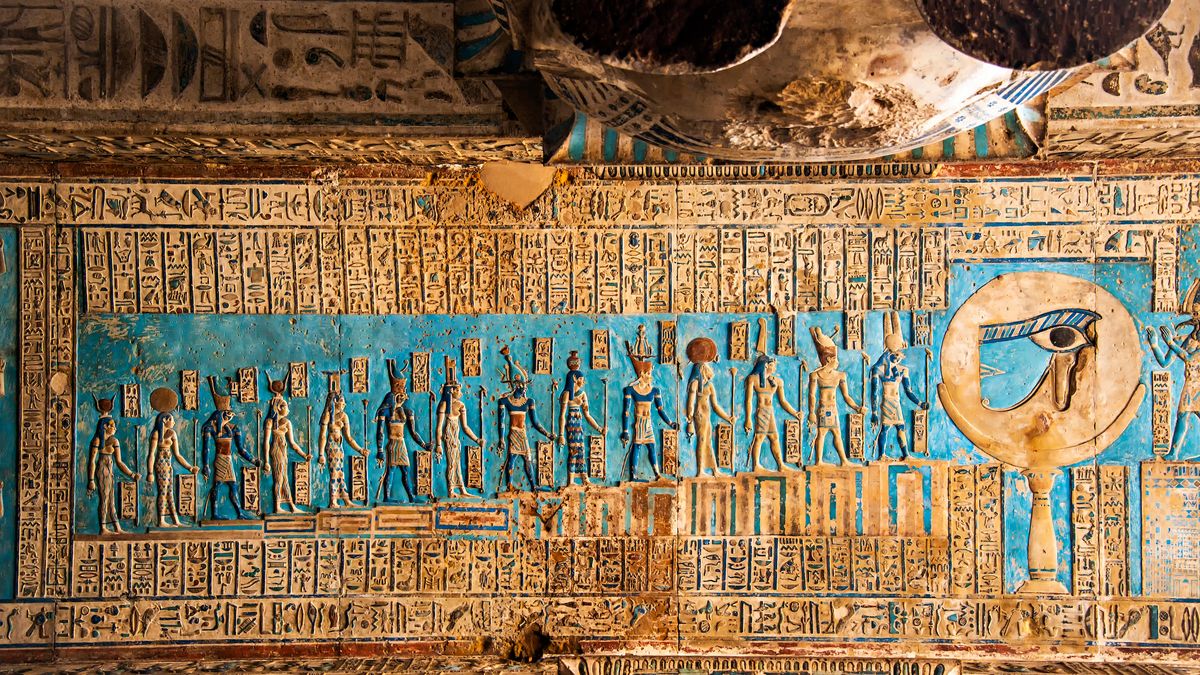

The Rosetta stone was the key to understanding ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. (Image credit: Fotosearch via Getty Images)

Allen stated that Champollion knew Coptic, the last stage in ancient Egyptian Coptic writing in Greek letters. He could determine the sound value from hieroglyphs by comparing the Egyptian hieroglyphs with the Greek translation on The Rosetta Stone.

"Champollion's Egyptian Coptic knowledge meant that he could see the connection between ancient symbols he studied and sounds that he knew from Coptic words," stated Margaret Maitland (principal curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at National Museums Scotland). Maitland noted that Champollion was suggested Coptic by Rufa'il Zakhr, an Egyptian scholar.

"Champollion studied Coptic together with Yuhanna Chiftichi (an Egyptian priest based at Paris), and Champollion." Maitland stated that Arab scholars already knew the connection between ancient and later forms Egyptian languages [such as Coptic]," Maitland added.

Stauder stated that "Egyptian hieroglyphs couldn't have been deciphered with Coptic."

Three decipherment problems

Although hieroglyphs from Egypt were deciphered in 19th-century Egypt, many ancient languages are still not fully understood today.

Allen explained to Live Science that there are three types of decipherment issues. Allen said that Egyptian hieroglyphic writing falls under the category of cases in which the language is known but not the script. In other words, scholars knew the Coptic language of ancient Egypt, but didn't know the meanings of the hieroglyphic symbols.

Related: Latin is dead?

Allen stated that another decipherment problem arises when "the script is not known but the language is." "Examples include Etruscan which uses the Latin alphabet and Meroitic which uses a script derived form Egyptian hieroglyphs. Allen stated that while we can understand the words in this instance, we don't really know what they mean. (The Etruscans were in Italy while the Meroitics lived north Africa.

Allen stated that the third type of decipherment problem involves "neither a script nor a language being known". Allen noted that one example is the Indus Valley script, which is located in what is now Pakistan and northern India. Scholars don't know the script or its language.

Combining languages

Scholars working on undeciphered scripts will learn a lot from Egyptian hieroglyphs' decipherment.

"One of the major theses of our book" is that it's better to look at an ancient script within its cultural context," Diane Josefowicz, who is a writer with a doctorate of science history, said. She co-authored "The Riddle of Rosetta: How an English Polymath & a French Polyglot Discovered The Meaning of Egyptian Hieroglyphs." (Princeton University Press 2020). Josefowicz pointed out that Thomas Young (1773-1829), an English scientist, also attempted to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. Josefowicz shared this information with Live Science via email.

Josefowicz stated that Champollion was more interested in Egyptian history, culture, and that he was the first to extensively use Coptic, a late version of ancient Egyptian Egyptian, in his study on hieroglyphics.

Stauder said that it is crucial to be able to translate an untranslated script into a language or group of languages. Champollion had to be able to read Coptic to understand Egyptian hieroglyphs. Stauder noted that scholars who deciphered ancient Mayan symbols used their knowledge of modern Mayan languages to decipher the glyphs.

Stauder pointed out that Meroitic is now being deciphered by scholars because they know it's related to the North East Sudanese language group. "The further decipherment of Meroitic is now greatly helped by comparison with other languages from the North-East Sudanese and the reconstruction of substantial parts of the lexicon of proto-North-East-Sudanese based on the currently spoken languages of that family" Stauder said.

Maitland also agreed, stating that "languages that are still alive but are currently under threat could be crucial for progress with still unciphered ancient scripts."

Original publication on Live Science