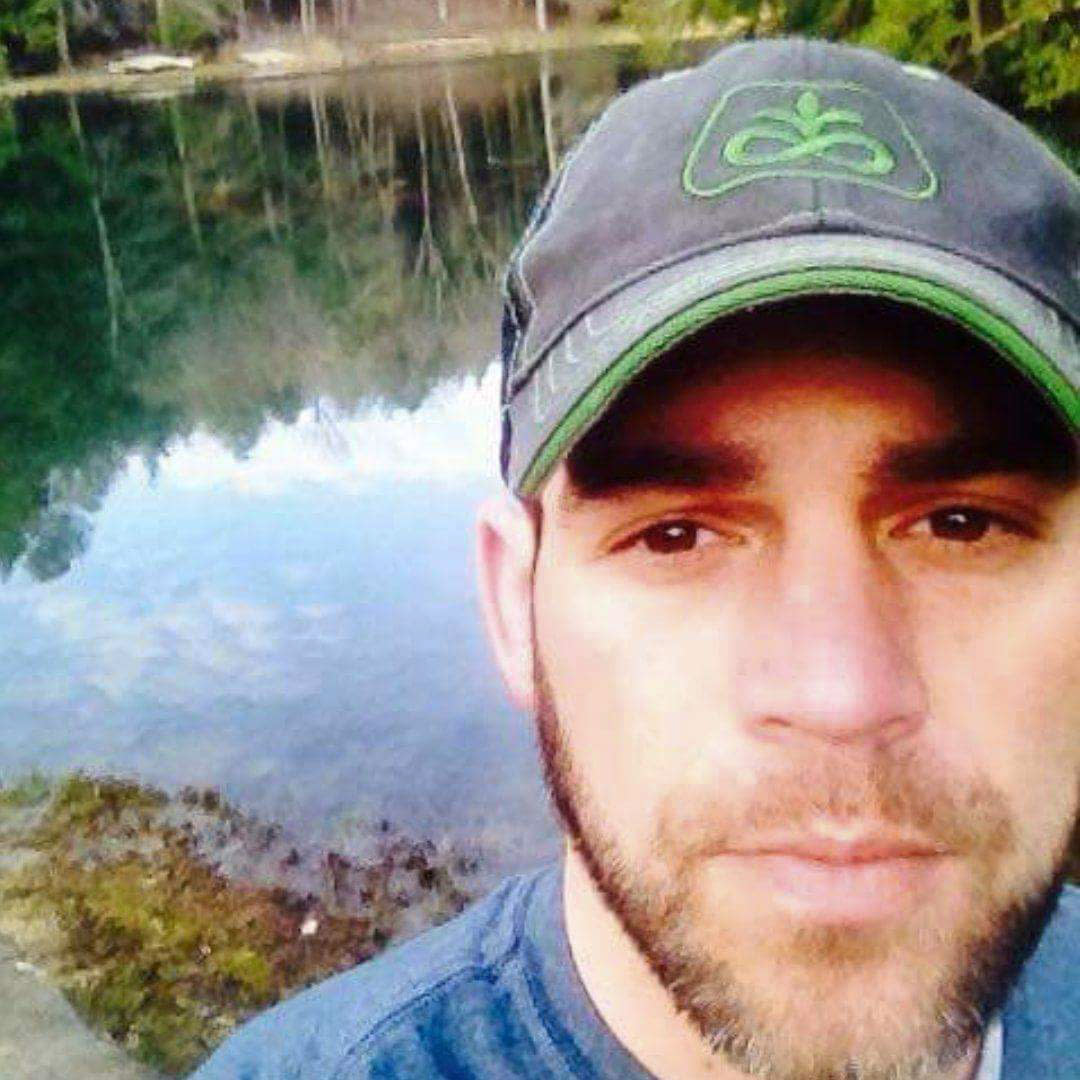

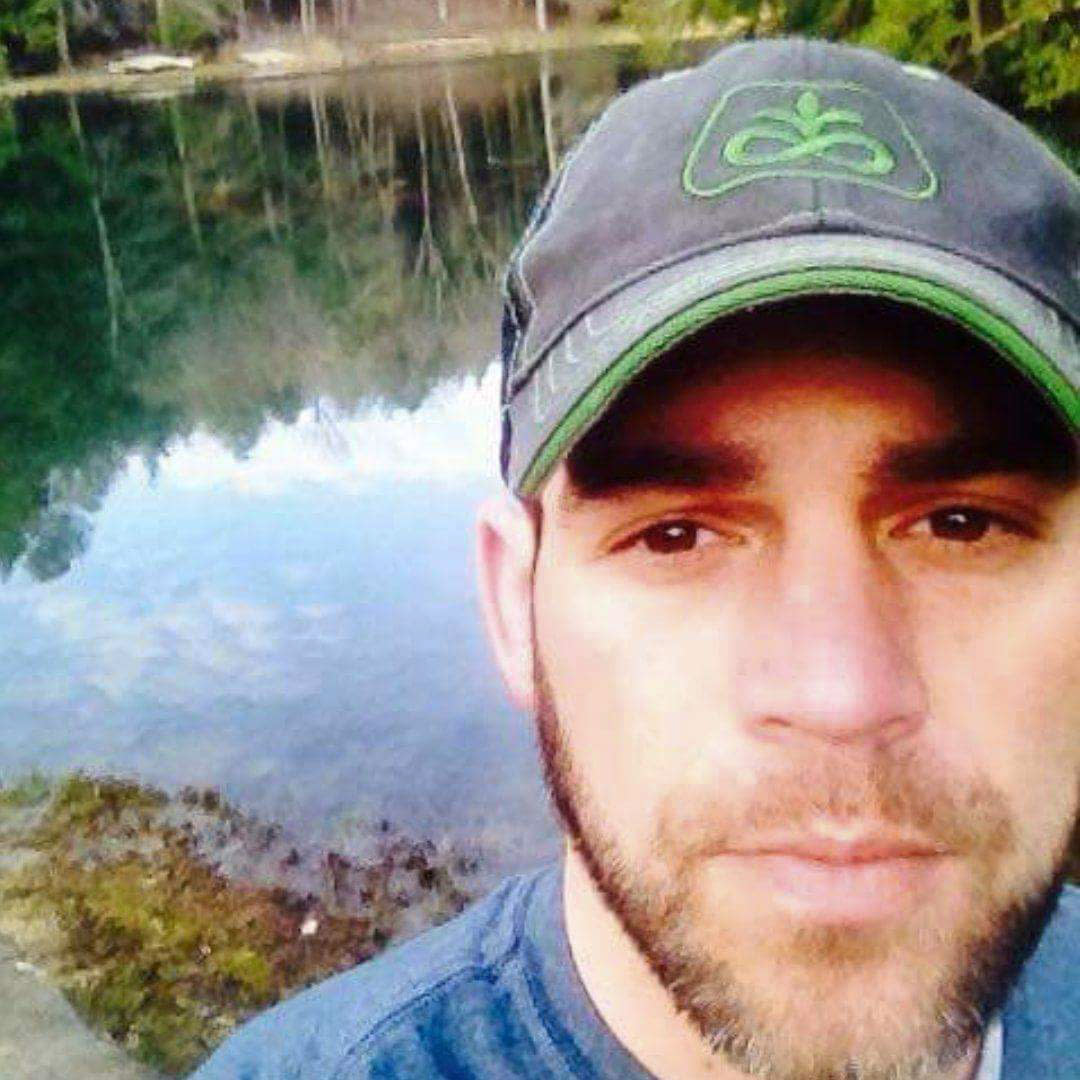

The New York Times has an undated photo of Christopher Jacobs holding a gun to the head when he was shot by a Kentucky state officer on November 1, 2017. (via The New York Times).PIPPA PASSES (Ky.) The man known as Doughboy for his entire life had been fleeing the state police for months. He was seen running down a creek bed and flooring it from a gas station. He also visited his children at 2 a.m., when he believed troopers wouldn't be there.Christopher Jacobs (28 years old) was charged with methamphetamine manufacturing. He told his family that he couldn't bear to return to jail. However, he said that he also feared that the police would shoot him, even though he was childhood friends with the officers who patrol this stretch of eastern Kentucky.According to police records, Jacobs crawled under a mobile home and fled when a sheriffs deputy brother and a state trooper pulled into Jacobs' driveway on Hemp Patch Road.Subscribe to The Morning newsletter of the New York TimesHis second was to shout, "Don't kill me!" He then jumped in his Chevrolet Impala and attempted to flee. The officers used Tasers to disarm him as he tried to get the car started. He then drove a police cruiser empty.Leo Slone was a trooper who grew up with Jacobs. He once saved his life by saving his life from a drug overdose. Slone shot Jacobs three times. Jacobs was killed instantly.The Marshall Project and Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting spent one year investigating the urban murders that have been so prominent in U.S. cities.Officers shot approximately 1,200 rural residents between 2015 and 2020. In cities, there were at most 2,100 deaths according to The Washington Post's analysis. No comprehensive government database is available.Data analysis revealed that the rate of rural police shootings was 30% lower than that of urban shootings, but that rural shootings mirror many of the same dynamics as those that are under scrutiny in cities.The analysis showed that rural shootings were less common than urban ones, with a decrease of about 9% in rural areas compared to 19%.Continue the storyProtests and calls for change have been sparked by high-profile police shootings in urban areas, such as Breonna Taylor's death in Louisville, Kentucky. Rural deaths are rarely covered by the media or the public. Rural officers are less likely to have body cameras and police shootings in remote areas are not often captured on video.The Kentucky State Police's rural shootings, which were the most fatalities in six years, are a reminder of what makes these encounters different from other police killings. They also show how they fit into larger patterns across the country.At least 41 people were killed by Kentucky state troopers during this period, 33 of them in rural areas. Reporters interviewed over 100 people, reviewed thousands of pages and hundreds of court documents, and conducted data analysis to examine the deaths.The difference between the rural shootings in Kentucky and elsewhere was the fact that the majority of those killed were white. The rural majority is made up of white people in almost every state. Nearly two-thirds (or more) of those killed in rural shootings by law enforcement officers in the United States were white. Only 10% were Black. In cities, 37% of the population was Black while 31% were white.However, there were some states where adisproportionately high percentage of Blacks were killed or shot by police compared to the rural population. Alabama, Virginia, and Louisiana are just a few examples. In Louisiana, Blacks accounted for almost 20% of rural residents, but 37% of rural police shootings.The rural Kentucky shootings were also closely related to urban and rural police shootings throughout the country. According to police records, the majority of rural Kentucky victims were men. Two-thirds were armed and armed with guns. Police records reveal that most of the victims had a history of drug addiction and mental health issues, with some even in crisis situations, which troopers were unable to stop. Many of the shootings took place in poorer states.The data shows that rural shootings are similar to other types of police shootings in the country. However, they rarely result in indictments or prosecutions. Kentucky is an exception to this rule, as the state police conduct their own investigations without a third party review.Although the Kentucky State Police declined to interview, they provided a written statement. The agency did not comment on specific cases but defended its record in public safety, training, and the use deadly force.It takes any use force seriously and trains troopers in deescalation. The agency also reviews force use to make sure force is justifiable to protect the trooper or officer. The statement was made by Billy Gregory.Rural Kentucky shootings were more than half of those examined. According to the Rand Corp, 55% of Kentucky's households have guns. In addition, at least 9 of 33 rural Kentucky shootings were caused by law enforcement officers who fatally shot someone who had fired on them.One Kentucky trooper was killed while on duty during that period. This incident was a warning sign for officers who have to deal with the common reality of the job: being alone.Experts in policing said that solo officers can be more inclined than others to shoot, because they know there is backup. Ralph Weisheit, an Illinois State University professor in criminal justice, stated that working alone can affect the mentality of officers on the scene.Former state police officials stated that working alone is just one of the many challenges facing the state police. Another factor is methamphetamine abuse, which was responsible for about half the rural deaths that were traced back to toxicology reports.The agency stated that it has required cadet training in mental health first aider since 2019. However, it has not used the same practices as big-city police departments to try and prevent violence such as using body cameras. There have been contradictory accounts by troopers and witnesses as to how the fatal encounters with police took place, despite not having video.At least 20 of the 33 shootings in rural Kentucky were presented to grand juries. None of the officers were charged.Officers met Bradley Grant in distress on May 20, 2018. He had been sober for years and, like nearly one-quarter of those shot by Kentucky troopers rurally, had recently threatened suicide. Police records show that he was also struggling.Troopers arrived at the house they believed Grant might be living in to search for a man they believe was responsible for beating and molestation of a child. Instead they found Grant pressure washing the porch. Grant's mother, who was riding along with one of the officers, told Grant that Grant wasn't the abuser.Grant entered the house and was followed by officers even though they didn't have a warrant.Detective Aaron Frederick opened a door to find Grant, who was pointing a shotgun at himself and saying, "Shoot me!" Frederick later claimed that he had repeatedly told Grant to drop the weapon and then fired at him. Grant died soon after.Frederick declined to comment.Federal Judge dismissed the claim of excessive force and agreed with officers that the circumstances justified the shooting. The judge also ruled against Grant's constitutional rights, stating that troopers entered the house without permission or a warrant. The appeal is being made by the state police.The deaths of troopers in rural Kentucky are not enough to cause protests and widespread distrust. Families, including those of the Grants, have expressed concern about the agency's investigation into shootings by its officers. Jacobs' family and friends shared these concerns.A grand jury declined to indict Jacobs' trooper less than three months after Jacobs' death.Terrie Jacobs, Jacobs' mother, stated this spring that she was still grieving her son. She said that she would carry this pain with her all her life. They will bury me.2021 The New York Times Company