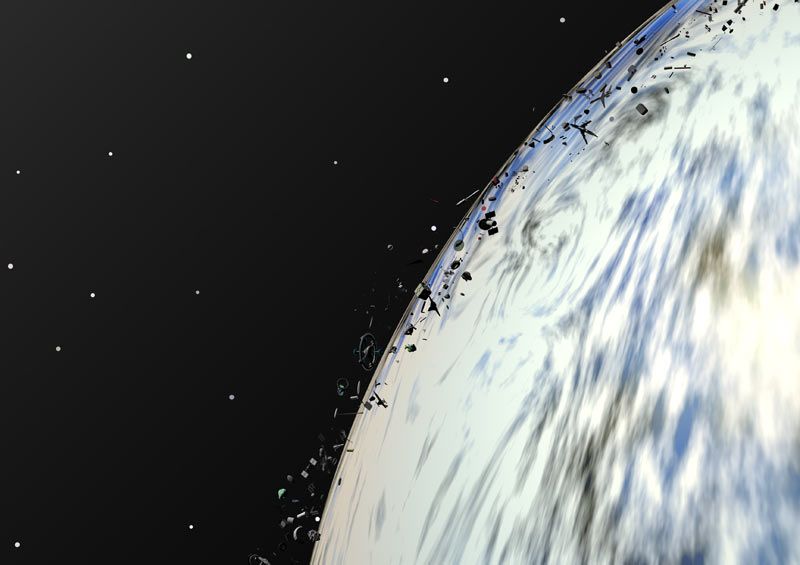

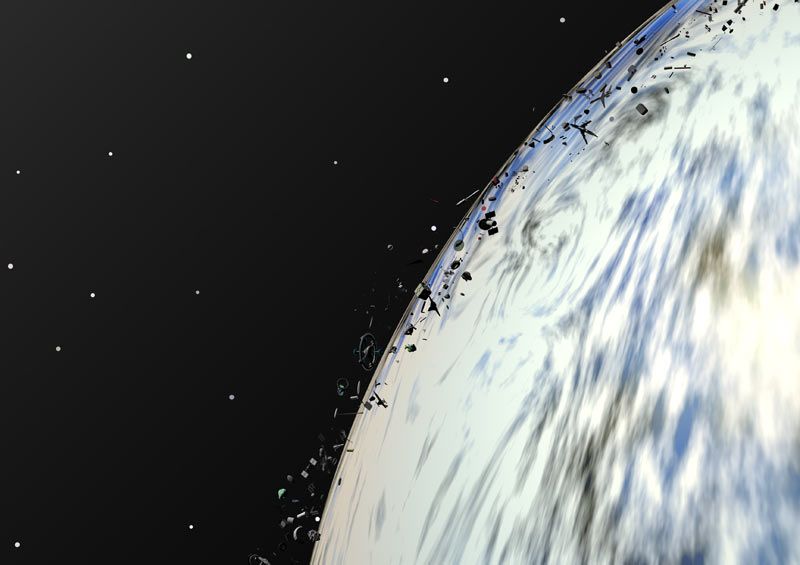

Paul M. Sutter, an astrophysicist from SUNY Stony Brook is host of "Space Radio" and "Ask a Spaceman," and author of the "How to Die In Space" book. This article was contributed by Sutter to Space.com's Expert voices: Op-Ed and Insights.Over 20,000 pieces of space debris have been tracked and are currently orbiting Earth at a speed of 15,000 mph (24,000 km/h). These debris pose a threat to future space missions and no one is doing anything to remove them. Why? It's just too difficult.The U.S. military sought a new method of communicating with its troops around the world in the 1960s. An enemy could not use the radio signals bouncing off the ionosphere to communicate with them if they cut undersea cables. This was unreliable. The Cold War-era solution Project West Ford is a program that will launch 480,000,000 tiny copper needles into space. This will give Earth an artificial ionosphere as well as a reliable means of communicating.The program was cancelled after the first batch had been successfully launched. One reason was the rapid development of communications satellites. Another reason was the realization by everyone that it was probably a bad idea to send countless pieces of junk into space.Related: How can tiny pieces of junk from space cause such incredible damage?The amount of space junk that has been created since then has only increased. According to NASA, Earth orbit contains more than 23,000 objects greater than 4 inches (10 cm), half a million larger than 0.4 inches (1 cm), and perhaps 100 million smaller. There's a lot more up there than you might think: debris from spacecraft, spent rocket boosters and lost gear (including a glove and a blanket), paint flecks and bits of metal, frozen propellant and lots of bolts.Space is becoming messy and dangerous.You are invited!The U.S. launched a Delta II rocket to launch an infrared monitoring satellite into orbit on April 24, 1996. The U.S. Ballistic Missile Defense Organization launched an infrared-monitoring satellite into orbit using a Delta II rocket. Lottie Williams, a Tulsa resident, was doing her business in a park about a year later when she was struck in her shoulder by a piece of aluminum and fiberglass measuring 6 inches long (15 cm). A few hundred miles away, another piece of the second stage from that Delta II rocket crashed.Williams was the first and so far only person to be hit by falling space junk. However, an estimated 100 tonnes of space junk make it to Earth each year. Most of this junk falls into the ocean, so it is not a danger to humans.Related: How can asteroids, space weather, and space debris be detected before they reach Earth?There's more. China tried its anti-satellite technology in 2007 by throwing a huge, high-velocity slug at an orbiting weather satellite. It worked, and more than 3,000 pieces were tracked in orbit. A (functional) Iridium communications satellite was to be silently slinged by a (dysfunctional Russian military Kosmos satellite, with nearly 2,000 feet (600m) left). It didn't and that event set off another avalanche involving 2,000 debris objects.The International Space Station must maneuver around a piece of junk about once per year while astronauts are safe in their Soyuz capsules. Famously, the space shuttle collected holes and craters from its windows, radiators, and thermal tiles due to collisions with mostly paint chips.Even though they are small, the speed of space junk objects makes them very dangerous, increasing the risk for future space missions. Many are concerned about the emergence of the "Kessler Syndrome," a condition in which enough debris triggers more collisions, causing even more debris to fall on Earth, making it an uninhabitable and dangerous place.Laser brooms. Boosters, nets, and harpoons.Private companies and national governments are often slow to respond. The majority of efforts are focused on avoiding the creation of space junk. To minimize the possibility of an explosion, rockets must exhaust all their fuel and reactants. Satellites can end their lives by either going into orbit and burning up in the atmosphere, or if they are high enough they can push themselves into "graveyard orbit", hundreds of miles above any useful objects.These mitigation strategies can help to control space junk's spread, but they do not clean up the mess that's already there. The Earth's atmosphere can do some of this work by dragging down on any objects in low Earth orbit. However, depending on the orbit, it could take anywhere from a few weeks to several decades.Private companies and space agencies have developed a range of cleanup strategies. Other satellites could be pushed into the atmosphere or into the graveyard by special missions. This would use technology that is as old as civilization itself, harpoons as nets. Another plan calls for ground-based lasers that heat one side of the satellite to cause it to shift its orbit and become trapped in Earth's atmosphere.The ground-based laser is amusingly called a "laser brush" and all the proposals call to launch new satellites. This makes satellite cleanup extremely expensive. There's also the fact, that any "satellite cleaning" technology automatically becomes "remove an opponent's satellite form the sky" technology. Any proposal can quickly move into the murky waters that are defense, international diplomacy, and militarization.Our best strategy for now is to monitor, track and warn using a network satellite- and ground-based observatories. We will keep our fingers crossed.Listen to the episode, "Who's going to clean up all this space junk?" Listen to the "Ask A Spaceman Podcast" available on iTunes or askaspaceman.com. Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.