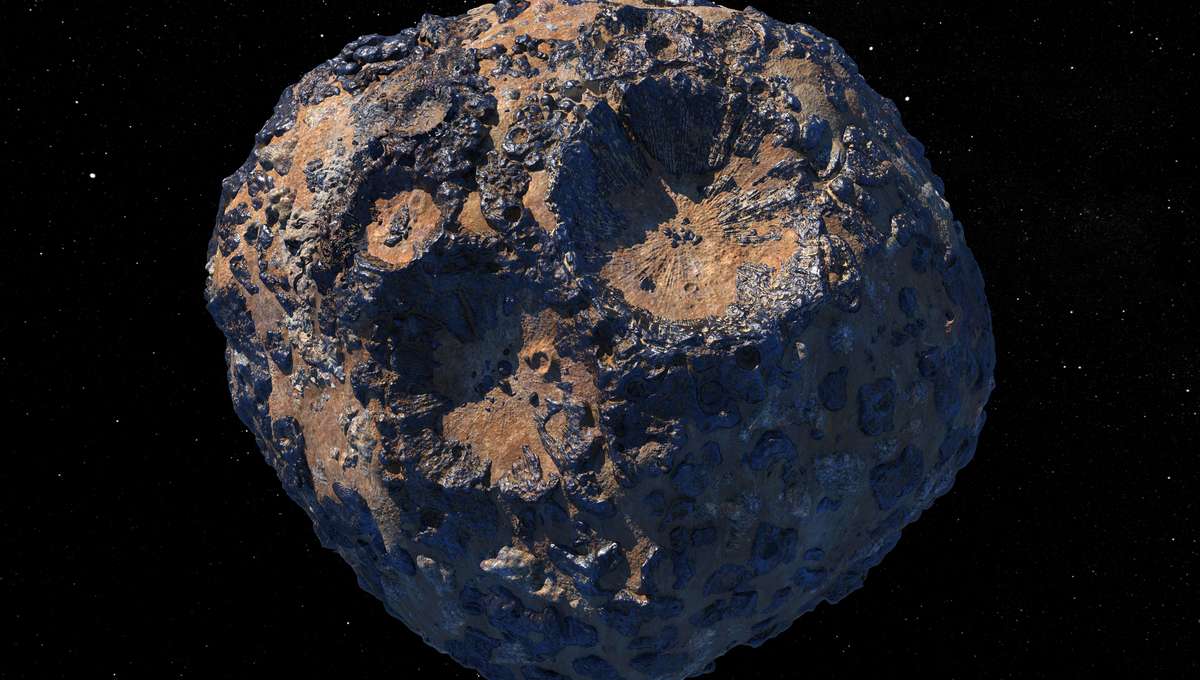

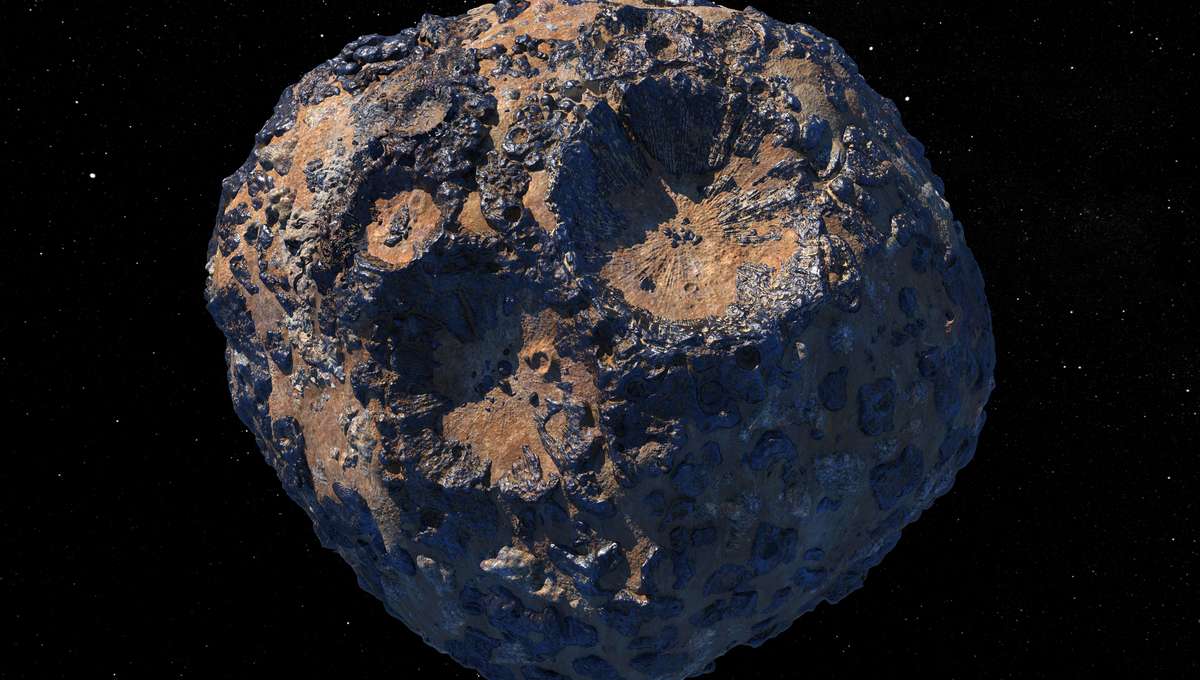

The Psyche mission is very exciting to me. This NASA spacecraft is scheduled to launch in 2014. It will reach its target in the main asteroid Belt four years later: The odd asteroid 16, Psyche.Most asteroids have rocky surfaces. Some even have ice beneath their surface. However, Psyche is an M class asteroid. This means it's highly metallic (mostly nickel and iron). It is large, with a diameter of over 200 km. This makes sense, even if it is metallic.Psyche is the first asteroids that spacecraft have visited so far. They are all rocky. The upcoming mission has increased interest in the object.This paper, just published by scientists*, contains some interesting updates about this strange little world of metals.Animation of 16 Psyche's orbit based on model models. The asteroid 16 Psyche measures approximately 250 km in circumference and is made primarily of iron, which is a rare trait among asteroids. Although it is too small to be able to see the details of its surface directly using telescopes, astronomers have been able to create a model of its form by making observations with various telescopes. Michael Shepard, a planetary scientist, animated the model spinning. He first looked up from the south and then down from north. The long axis of this asteroid is marked by the red stub. Credit: Michael ShepardTo determine the size, shape and topography of the asteroid, they used observations of Psyche using the Very Large Telescope, Arecibo's Keck telescope, ALMA, Arecibo and stellar occultations. They have some interesting results.Overall, Psyche looks like a potato and measures 278 238 171km in length (roughly 5 km). It spins once per 4.2 hours.They discover several large features on the surface, including an Alpha depression (which they call it). There are also two large flat areas called Bravo and Charlie. A 50-km feature (Foxtrot), which may be an impact crater, is located at the north pole of the asteroids. Another feature is found near the south pole (Eros).Zoom In A map of the asteroid Psyche, created using radar observations and visible light. The brighter colors indicate that it is more reflective in visible sunlight, while the white areas are reflective on radar. These could be ferrovolcanoes. Credit: Shepard et al. 2021A little background is required for the next features. As Psyche spins it becomes brighter and dimmer with visible and infrared lighting. This is because more and less reflective areas on the surface become visible. Keck and VLT observations can be used as a map to determine where they are.Radar is used in the Arecibo observations. These radio waves, which were sent out by the large dish, struck the asteroid and were reflected back to Earth. This can be used for mapping the shape of an asteroid (a radar signal that hits a depression travels slightly longer, so timing them can generate topographical maps), but it can also give clues as to the surface composition.This is where the fun begins. They found that both visible light as well as radar were reflected on several spots. These spots are bright in both visible and radar light.This is why it is so significant. It is not known how Psyche was created. Billions of years ago, smaller bodies, called planetesimals, collided with each other and grew. Some were rocky and some metal. When the object was large enough to be able to feel gravity, the molten and lighter metals would sink into the core. This is known as differentiation.One idea that has been around for a while is that Psyche was struck by a massive impact. This ripped away its outer layers and left only the metal core. Its density was estimated to be around 4 grams per cubic cm, while iron is twice as dense. It is difficult to explain this density if it is a pure metal world.Zoom In Artwork showing what the rock and metal asteroid Psyche could look like. New theory suggests that these craters may be ferrovolcanoes or volcanoes that have erupted molten metallics. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/Peter RubinThere are many other options. Another possibility is that the impact split it into smaller pieces that were then reaccumulated. This would make it porous. It is like a box full of metal and rocks instead of one solid body. Although we see smaller asteroids, Psyche is 100x larger. It's not clear how anything this big could be so porous.Another idea was presented by the paper authors: Psyche is still a distinct world with a metal core, rocky crust, and its ferrovolcanic.This topic has been covered before. Volcanism on Earth is molten rock. On some asteroids, icy moons (and Pluto, of that matter), we find evidence of cryovolcanoes. These are eruptions of liquid water which freezes to a solid. One of the most fascinating phenomena is ferrovolcanoes, which are volcanic eruptions of molten metal. The idea was that the core remained molten and the surface became a rocky crust. However, the molten metal would have erupted from the areas where the crust was thinner.This would explain the observations. It has been proven that the surface is covered with plenty of rock, but it is also heavily layered with metal. These ferrovolcanoes would likely be located in areas of the surface that they observed were visible and radar-readable. The metal that flows out would be solidified and reflective to both wavelengths.This is the beauty of it: It makes a clear prediction. If the spacecraft sees that those spots are ferrovolcanoes when it gets there, it will be able to tell that Psyche's strong support for it is differentiated and not the naked core that was once a much bigger object.In just a few more years, we will find out if they are right.I am biased in my excitement about this mission and the asteroid. Meteorites are pieces of asteroids that have fallen to Earth. I am a collector. There are a few rocky ones I own, but I prefer the metallic ones. They are just intrinsically cooler to me. Metal asteroids can be rare and Psyche is the largest. Some meteorites may actually be from Psyche.Although I don't believe any meteorites that I have are from Psyche it makes the connection with the asteroid even more tangible. In just five years, we have our first close-up photos and data from an M class asteroid. It will be amazing to see.*My sincere thanks to Michael Shepard, the lead author of this paper.