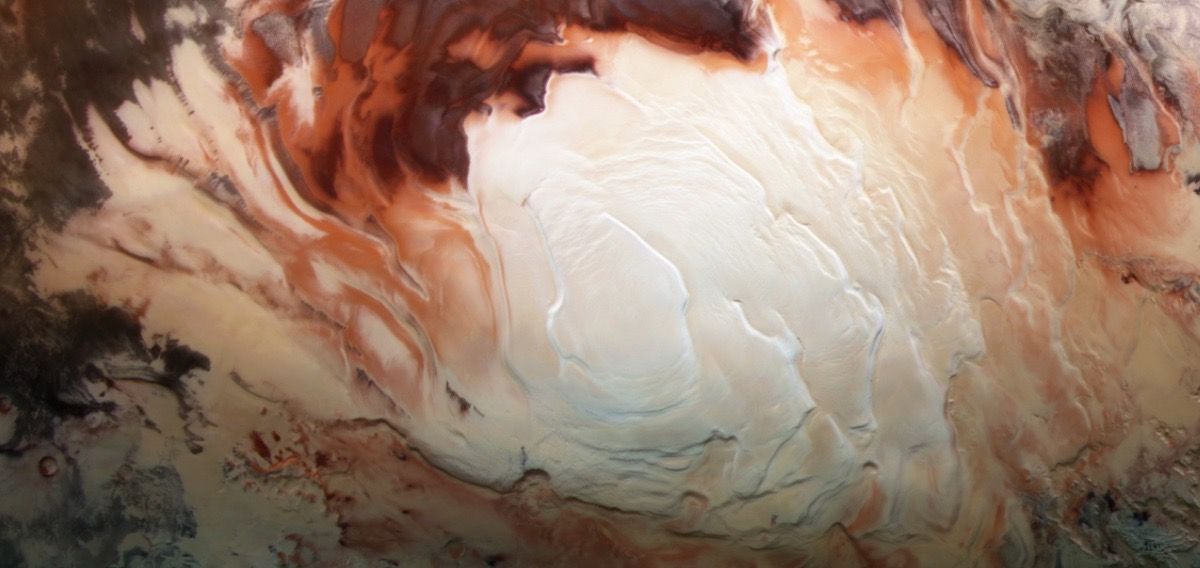

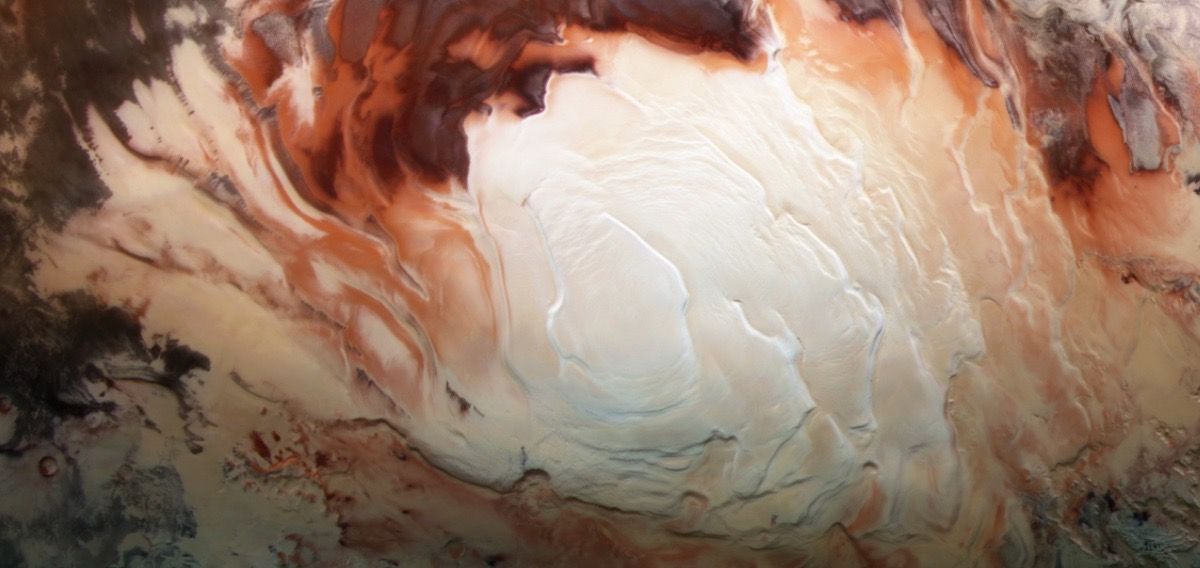

This image shows the bright white area of Mars Express's December 2012 spacecraft. It is an image of the icy cap at Mars south pole made of frozen water, carbon dioxide, and other elements.New research suggests that bright reflections detected by radar beneath Mars' south pole may not have been underground lakes, but clay deposits.Scientists have known for decades that water exists below the polar caps of Mars. Researchers using the MARSIS radar instrument on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft discovered evidence of a lake beneath the Red Planet's south polar ice caps. In 2020, however, they also found signs of a few super-salty lakes. Scientists noted that these lakes could have been remnants of water once found on the surface.According to Isaac Smith (a Toronto-based planetary scientist) and his coauthors, liquid water would need to be formed and maintained at this location on Mars.Related: A photo timeline of the search for life on MarsYork and his team believe that radar reflections can be explained by clay minerals found in Mars' south polar region.Smith stated that there was some skepticism among the Mars community about the lake interpretation. However, no one had presented a plausible alternative. Smith spoke to Space.com. It's thrilling to be able show that there is another explanation for radar observations, and that the material is where it should be. I love solving puzzles and Mars is full of them.Scientists focused on smectites minerals, which are clays whose chemical structure is more similar to that of volcanic rock than other clays. After interacting with water, eroded volcanic rock undergoes mild chemical changes to form smectites. They noted that these clays can store large amounts of water.Smectites are very abundant on Mars. They are concentrated in the southern highlands. Smith stated that although they are most common near volcanoes in Alaska and Central America on Earth, they can be found anywhere on the continent.The researchers chilled smectites in a laboratory to minus 45 degrees Fahrenheit (minus43 degrees Celsius), which is the same temperature as Mars. The researchers found that water-laden smectites can produce bright radar reflections, which are detected by MARSIS (short for Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Soundsing). This is even when they are mixed with other materials.Smith and his colleagues also discovered evidence of smectites when they analyzed visible and near infrared data from Mars' south Pole. They speculated that smectites were formed at Mars' south Pole during warm spells when water was present. These clays with water content were later submerged under water ice.The colored dots indicate locations where ESA's Mars Express orbiter spotted bright radar reflections at Mars south pole cap. These reflections were once thought to be subsurface liquid water. However, their presence and proximity to the frigid surfaces suggest that they could be something else. (Image credit: ESA/NASA/JPL-Caltech)Smith stated, "Looking backwards, to when Mars had been much wetter, this supports evidence of liquid water being present over a greater area than we expected." These clays are located at or below the south polar caps, so it must have been warm enough to support liquids.The researchers concluded that smectites were a better explanation for the bright radar reflections observed there, rather than super-salty lake.Smith stated that science is a process and that scientists are always striving for the truth. Smith said that showing that liquid water can also make radar observations does not mean it was wrong for 2018 to publish the first results. This gave many people new ideas for experiments, modeling, and observations. These ideas will be applicable to other Mars investigations, as they are already for my team."Smith stated that in the future, he would like to do the measurements at colder temperatures with a wider range of clays. "I suspect that there are other clays on Mars that can make these reflections. It would be a good idea to follow up with them."Today, July 29, the scientists presented their findings in Geophysical Review Letters.Follow us on Facebook @Spacedotcom and Twitter @Spacedotcom