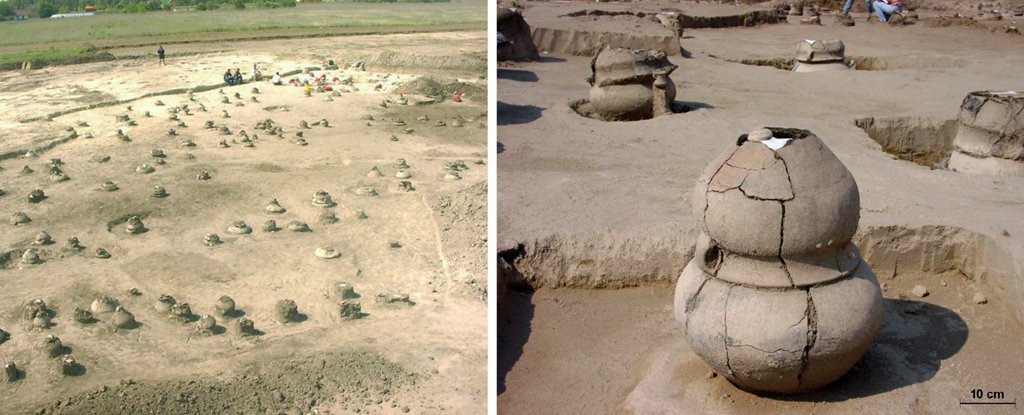

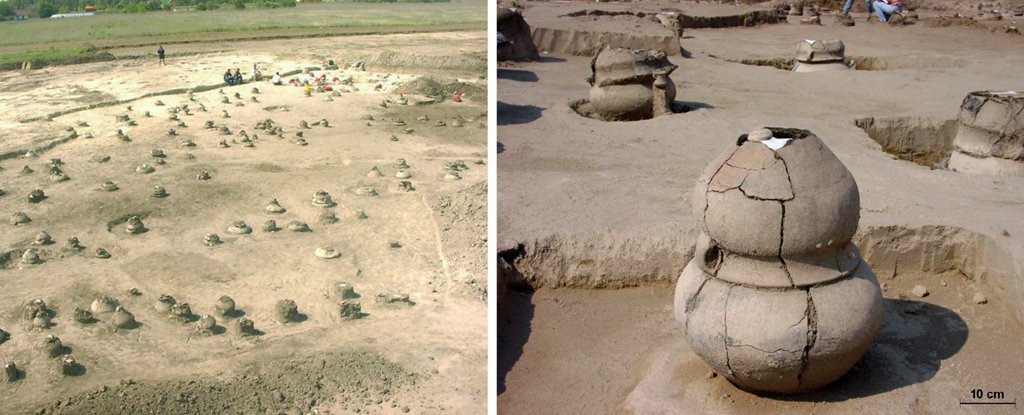

A well-preserved grave can serve as an obituary. It will detail the life, health, and fortunes of the deceased.Technology has made it harder to determine how well-preserved an individual body must be to allow experts to extract a biography. One young woman from the Bronze Age in central Hungary was able to tell her tragic story through cremation.Researchers from Hungary and Italy have analysed a variety of samples of human remains and artifacts found in an ancient cemetery that dates back to the 4,000-year-old Hungarian city Szigetszentmikls.The 'urnfield cemetery' is composed of hundreds of clay pots, buried about a kilometer away from the Danube shore. It preserves archeological data that relates to a long-lost culture called the Vatya.We know very little about the Vatya. It is based on scattered fortified structures, cemeteries and cemeteries that contain cremated bodies buried within ceramic urns. This is not enough information to provide a glimpse into the lives of people who occupied Danube basin for approximately half a century starting around 2100 BCE.One of the largest urnfields can be found near Szigetszentmikls. It was discovered during a rescue excavation just before construction of a new grocery.A total of 525 burials were discovered within half an acre (about one acre). Most of them consisted of bone fragments and ash with occasional grave goods made from ceramic or bronze.Researchers took 41 samples from 29 burials. They also examined 26 urn cremations.One of these urns stood out among the rest. It was coded gravesite 241, and contained more luxury items, including a gold hair ring and bronze neck rings as well as two bone pins.(Cavazzuti et al., PLOS ONE, 2021, CC-BY 4.0)Above: Bronze neck-rings, hair-rings in gold, and bone pins/needles.241's urn showed signs of respect from her community, and its design was unique in reflecting an early Vatya motif.There were bone fragments that indicated the grave's occupant was a woman in her 20s or 30s. Two infants, both very small, were with her. They were barely fetuses at 30 weeks gestation.While most urns only contained a small portion of the cremated body of the deceased, 241 contained much more. It was almost as though an extraordinary amount of care was taken to extract every tiny piece from the funerarypyre before burial.(Cavazzuti et al., PLOS ONE, 2021, CC-BY 4.0)Above: The bones of the woman (left) and her fetuses' bones (right).Despite being fragmented, her body contained small details about her life that could be revealed by analysis of its isotopes.For example, her molars contain layers of dentine material that capture biographical events and chemical signatures. Her conical portion of her femur would had been remodelled at a standard rate over time, while still retaining signs of nutrition.These signatures were used to create a picture of a woman born from faraway when she was around 8 to 13. This could have been a woman who was probably born in Southern Moravia, which is now the Czech Republic.Similar analysis of remains in other urns shows that her integration was not unusual. Other women came from places far beyond the locality of the burial site.It is possible to imagine this young lady marrying into the vatya community's higher ranks. She would keep her heirloom neck band as an emblem of her past upbringing, and her bone clothes pins and hair rings as gifts welcoming her home.Tragically, she would die in her prime while pregnant with twins. We don't know if the death she suffered was due to an early birth or something else.It's amazing that so few burnt remains can reveal so much about Vatya culture, despite the emotional story of number 241’s life.We can see traces of women who traveled from far away to establish distant ties. This may have reinforced allegiances, but it is almost certain that they had an impact on the power and politics of an older age.How many stories are out there that need to be told, and how can technology help?This research was published by PLOS One.