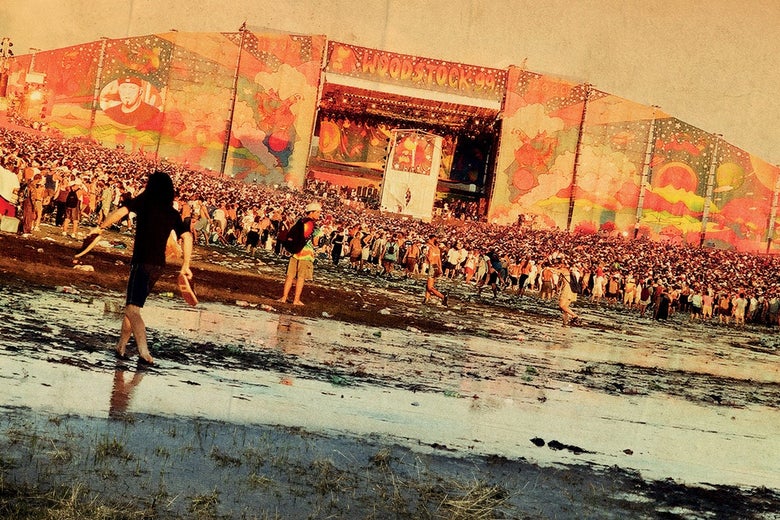

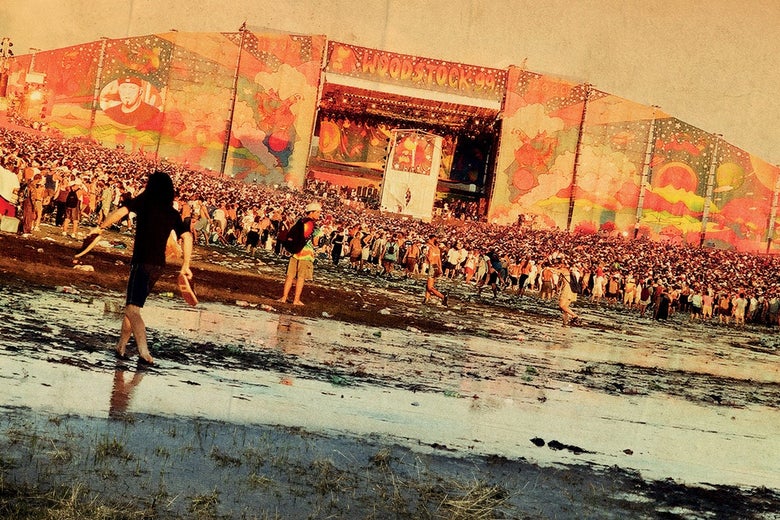

The HBOs first documentary series Music Box explores the 1999 Woodstock festival. This attempt to recreate the 1960s counterculture's defining moment leads to violence, sexual assaults and death. Woodstock 99: Peace, Love, and Rage is a documentary that shows footage of the actual festival. It also includes interviews with journalists, organizers, and musicians like Moby and Korns Jonathan Davis. Slate interviewed Garret Price, Woodstock 99 director (who also directed Love, Antosha, a documentary about the late actor Anton Yelchin), to learn more about the documentary's creation and what has changed. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.AdvertisementMarissa Martinelli: The documentary opens with you as a talking headAdvertisementAdvertisementGarret Price: This was not my choice.You didn't choose to appear.That's not the point. To introduce the films, they do that with each director. But go ahead, Im sorry.You say that it would be easy to make this a comedy in the opening of the documentary, but Woodstock 99 was more horror-oriented. I wanted to know why that disclaimer was made.Those were my words. This story, and all the stories about Fyre Festival, makes it easy to laugh at the 90s, our clothes, and the music of the time. Some of these stories are about the festival itself, as kids playing in mud that isn't.AdvertisementHowever, I was able to see some of the more serious issues and the tragic events that occurred that week. As the weekend progresses, I thought, "Man, this looks more horror movie-like." A bunch of kids are basically going to the woods, in this case, an Air Force hangar, for a weekend full of drugs, sex and rock n' roll. As in a slasher movie, every day and night brings more horror to the situation. This is how the story unfolded naturally in those days. This movie is more of a disaster or horror movie than a festival film.Subscribe to the Slate Culture newsletter and receive the best movies, TV, books, music, etc. directly to your inbox. Signing you up was not possible due to an error Please try again. To use this form, please enable jаvascript. Email address: I would like to receive updates on Slate special offers. You agree to our Privacy Policy & Terms by signing up. Thank you for signing up! You can cancel your subscription at any time.Some of the most memorable details from Woodstock 99 are already part of our collective cultural memories. Did you feel the documentary could have included details that were missing?AdvertisementThe cultural context was very important to me. What really excites me about telling this story is how I use it as a lens for all the sociopolitical, societal, and cultural things surrounding it. It is often forgotten that this festival was held right in the middle of the Columbine massacre, and the Y2K hysteria. This was the time of Girls Gone Wild and lad mags such as Maxim. It was a time when women felt objectified and disposable. There is also the Clinton and Lewinsky scandals, as well as his impeachment. There are so many interesting cultural events happening around this festival. While I'm not saying that these are the causes of some of the horrible events that occurred there, it does help to understand a lot of what is happening in our culture as a whole.AdvertisementIt was as if this festival is a mirror of what's happening in America right now. You start to see the problems at play when you learn more about this festival. It was just a lot of things going wrong. A tinderbox was formed, and it exploded.AdvertisementHow did you locate the participants and decide which ones to include?Bill Simmons was my partner, and they had previously done a podcast with Steve Hyden, a music journalist, about the same topic, Woodstock 99. When I suggested Woodstock 99 as a documentary, my partners were impressed. They had done research on the subject years before and they were able to help me. He was a consultant producer and introduced me to many of the get he had discovered in his research. We reached out to every musician and eventually got John Scher, Michael Lang and others to join us.AdvertisementHow were your interviews with organizers? Scher is the one I am most interested in, as he blames everyone for the chaos. He blames naked women. Fred Durst is the one he blames. He blames Fred Durst. How did you deal with that distrust?It's hard to not see them as the antagonists in this movie. John is one of their most tone-deaf characters. [Editors Note: Scher said at one point about some of the women assaulted that they shouldn't have been touched and it was something I strongly condemn. You know, I believe that the women who were running around naked are at least partially responsible.] But they're not horrible people. They fit the theme of power dynamics. John's comments aren't exclusive to him. Many people of a certain age believe some of these things. John believed it and continues to believe it, even though he hasn't reflected enough. I really hope that they will see this film and realize the serious issues under their supervision.AdvertisementAdvertisementHave you not heard from one of them? It is unknown if they have seen it.I haven't and I don't know if it will. They said what they think. I told the story I wanted to tell. I only hope they can see the point of view I used to tell the story.Girls Gone Wild was mentioned earlier. There is a lot footage of topless women in this movie, and some of them are being groped by camera. How can you show these women being exploited without exposing yourself to the danger of doing so?We were extremely sensitive to this issue and had to go back and forth hundreds times with our producers and other outside forces. To talk to women about it, we decided that as documentary filmmakers, our main focus would be to tell the story as it occurred on the weekend. We also wanted to highlight the things that were going on in the open.AdvertisementThis was the hardest part of this entire project. It's difficult to watch, I know. It leads to important conversations. This was the time that I was born. Woodstock 99 was my 20th birthday. I was 20 years old when Woodstock 99 took place in Texas. I didn't understand what was happening, but I did watch the pay-per view. I was more aware of FOMO and realized the issues only years later.AdvertisementAdvertisementPeople are drawn in by nostalgia. You become engrossed with the story and you begin to reflect on what you did as a man during that time. It was important for me to convey that. It feels great to see that this is happening. This time is being discussed again. It gets glorified as a great, carefree period in our culture. However, there were many problems.AdvertisementLiz Polay-Wettengel is interviewed about Fans Everywhere, and how it helped women who had bad experiences at the festival. Were there any women you spoke to who had negative experiences, or are they the ones we see in this documentary?We tried. We tried. We tried so hard to get as many people to speak but no one was comfortable speaking on camera. Because Liz was an attendee at the festival, she was a great get. She was so afraid that she returned home and created this website to help women who were assaulted at the festival. Maureen Callahan was also involved in the creation of an expo for Spin magazine in 1999. She had many sources and victims who were assaulted. Both felt like they were the best to get as filters for some of these horrific stories.AdvertisementAdvertisementI'm sure this is not your first question, considering the timing. However, throughout the documentary, you will see these diary entries by David DeRosia (the festivalgoer who died there), which are read aloud. A.I. was used in the controversial Anthony Bourdain documentary. I was curious about how you dealt with sharing the voice of someone who is no longer with you, given the controversy surrounding the recent Anthony Bourdain documentary that used A.I. to recreate his voice.This is the same device that I used for the Anton Yelchin doctor. It would be only with the permission of the family. Anton's mother asked me to contact Nicolas Cage so that he could read Antons diaries. This was David's best friend. To use this device, someone must be emotionally connected to the person. His friend David [Vadnais] was that person. He was the one who went with him to this festival and lost his friend.AdvertisementIt was a terrible experience for David [DeRosia] to lose his life. But it was also horrible for [Vadnais] for him to be there and see his friend for the final time during the festival and not know where it was. David [Vadnais]'s brother was also there and read his diaries. This added an emotional dimension to the film.AdvertisementYou spoke to David DeRosias' mother? Although I knew she had filed a lawsuit against this festival many years ago, I was unable to learn more about her.She declined, but I did. She knew David's friend David would be part of this. She understood that. Although she was a part of the podcast I produced, she didn't want to be in this film. I completely respected her decision.AdvertisementCoachella is presented as an idyllic alternative to Woodstock 99 at the end of the documentary. What do you think has changed about festivals and festival culture in the past decade?They have made a lot of progress in terms of security and access to potable water. Many of these lessons were acquired through Woodstock. There are still sexual assaults at festivals today, I don't think so. It is still a problem and there are many things that can be done to stop it. Coachella is also changing from what it was originally intended to be. Now, it's VIP tents, ticket tiers, and glamping. Another dynamic is at work. You will have a different festival experience if you have more money than someone who has general admission.AdvertisementFestivals still result in people dying, right? Bonnaroo is a place where someone dies almost every single year.Yes. Yes. Yes.These threads are culturally relevant from the late 90s up to the present. It was also very interesting to me. The #MeToo movement and other such topics were the subject of much discussion. You can see many of the issues that were so openly discussed in the late 1990s and why this movement was necessary. White male toxicity, which was not a term I used at the time in late 90s, is something I believe people draw from the parallel between Woodstock and where they are today.I did not want to tell the story in a didactic way. I simply wanted to give the facts. It is amazing to see the parallels people draw on their own. These discussions are taking place. This is when you know that you have made an impact on people. This is what I set out for.