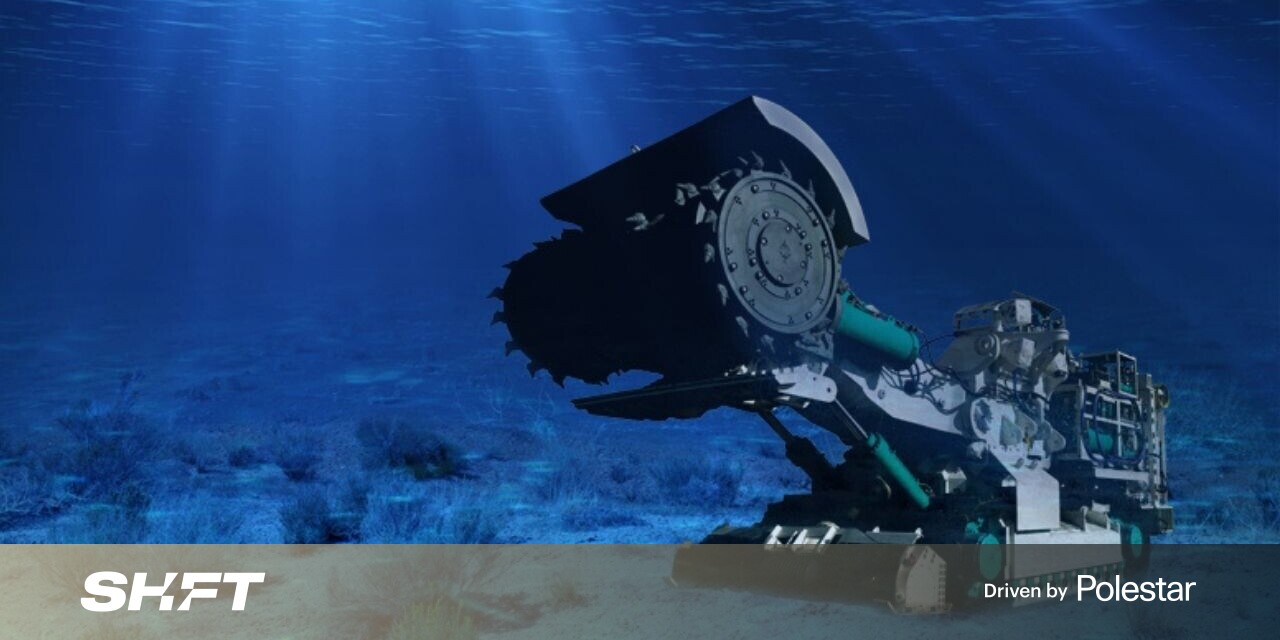

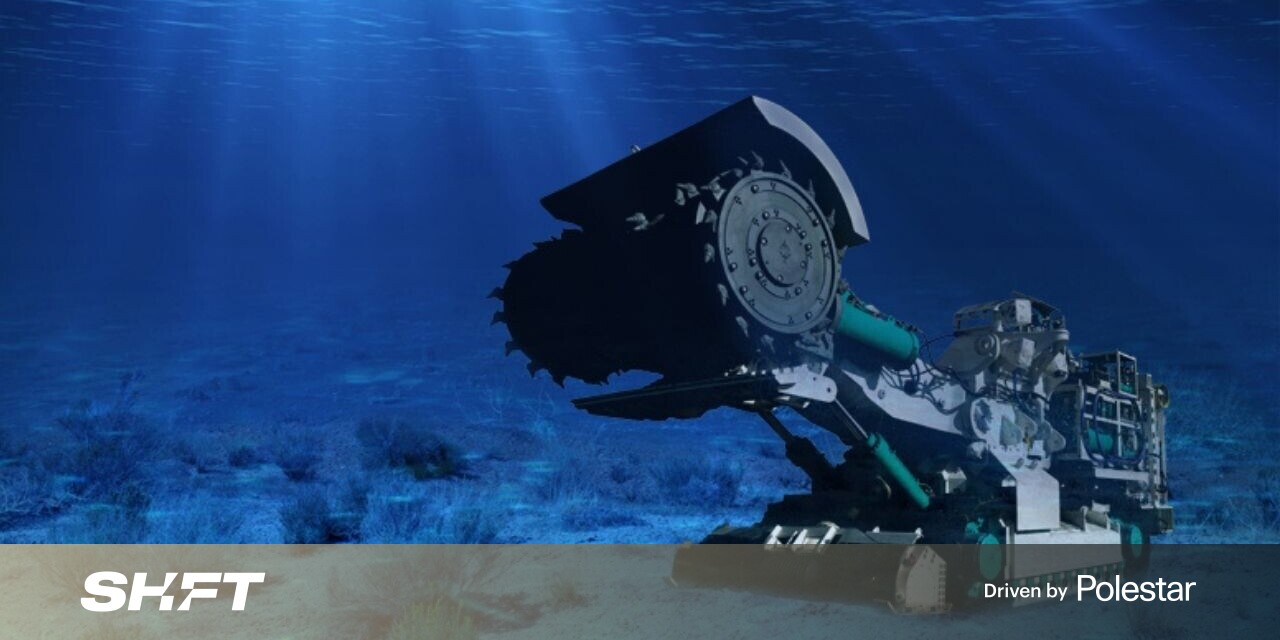

A news and commentary website that is independent of academics and journalists. A news and commentary website that is independent of academics and journalists.Although most Pacific islands have managed to escape the worst of COVID-19's effects, tourism, which is a key component of their economies has been severely affected. In June 2020, all visitor arrivals to Fiji, Samoa Tonga, Vanuatu and Tonga had stopped completely. Borders were closed and internal travel was restricted. Fiji, which was home to 40% of the GDP prior to the pandemic, saw its economy shrink by 19% in 2020.Offshore, there is an economic alternative. The Clarion-Clipperton zone (CCZ), a deep-sea tunnel that spans 4.5 million kilometres in central Pacific Ocean between Hawaii & Mexico, is one example of an economic alternative. It is home to small-sized, potato-sized polymetallic nodules, which are rich in nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper. They were formed by the accumulation of iron, manganese and other debris around them over many centuries.This trench contains around 21 billion tonnes worth of manganese nodules. The demand for these metals will skyrocket with the increase in battery development for electric vehicles and renewable power systems.Credit: EPA/Jens Buettner Large quantities of precious metals are required to produce grid-scale batteries and other green technology.Although most of the CCZ is located below the high seas, where no one state controls it, it's adjacent to the exclusive economic zones a number of Pacific island states like Tonga, Kiribati and Nauru. These states sponsor mining companies to obtain licences from the International Seabed Authority, which is responsible for managing the seabed in international waters. These companies would be able to examine the seabed to determine if mining is feasible and what its environmental impact might be.ISA has approved 19 exploration contract approvals to date. 17 of these are in the CCZ. The Metals Company, formerly DeepGreen Metals, is a Canadian company that has agreements with Tonga and Kiribati.It is difficult to predict the impact of deep-sea mining on species because so little information exists about the marine biodiversity. Scientists and environmental organizations have called for a moratorium in mining until more research is done.The Alliance of Solwara Warriors, a group of Pacific islanders representing the indigenous communities of the Solomon and Bismark Seas of Papua New Guinea have voiced concern at the insufficient information being provided to these communities regarding the possible impact of mining. Pacific civil society groups requested support from the British government for a moratorium in April 2021. Anote Tong, an ex-president of Kiribati, described deep-sea mines as inevitable and encouraged businesses to find safe ways to do them.But the time is running out. In 2021, seven exploratory licenses will expire. It is imperative that an international moratorium be adopted or that the ISA establishes a legal framework to determine the conditions in which extractive mining can occur.From exploration to extractionSince 2014, work towards this framework is ongoing. Despite this, the 168 members of the ISA assembly are still working towards a code to regulate extractive mining contracts. The pandemic hampered the ISA's efforts to reach an agreement by 2020. It is unclear if meetings will take place in 2021. The ISA will likely see exploratory contracts expire, which will increase pressure from mining companies and states that sponsor them to issue exploitation licences. The ISA regulates exploratory licences. Extractive licences are not subject to an agreed code without it.Even if there was a consensus, it would be difficult to enforce environmental safeguards. It is difficult to pinpoint the source of pollution and environmental damage when mining takes places in deep water. It is also difficult to determine the boundaries between different mining areas. It might take some time for the effects of mining to be felt in different ecosystems and habitats.Credit: V.Gordeev/Shutterstock The Polymetallic Nodule, taken from the Pacific Ocean.It is also unlikely that there will be an international consensus for a moratorium. The mining companies have invested a lot of money in developing technology to operate at these depths. Investors will also want to see a return. The royalties promised by the states that have sponsored mining contracts, including those on some Pacific islands, will be repaid.The Pacific island countries find themselves in a difficult situation. These countries are the most at risk from climate change, and they support strong action. The developed world's green transition will likely accelerate the demand for metals that rest peacefully in the oceans around these islands unless other solutions are found. The people of these islands will pay the high costs of deep-sea mines that were not done with sufficient caution.This article is by Sue Farran (Reader of Law, Newcastle University) and has been republished from The Conversation using a Creative Commons licence. You can read the original article.