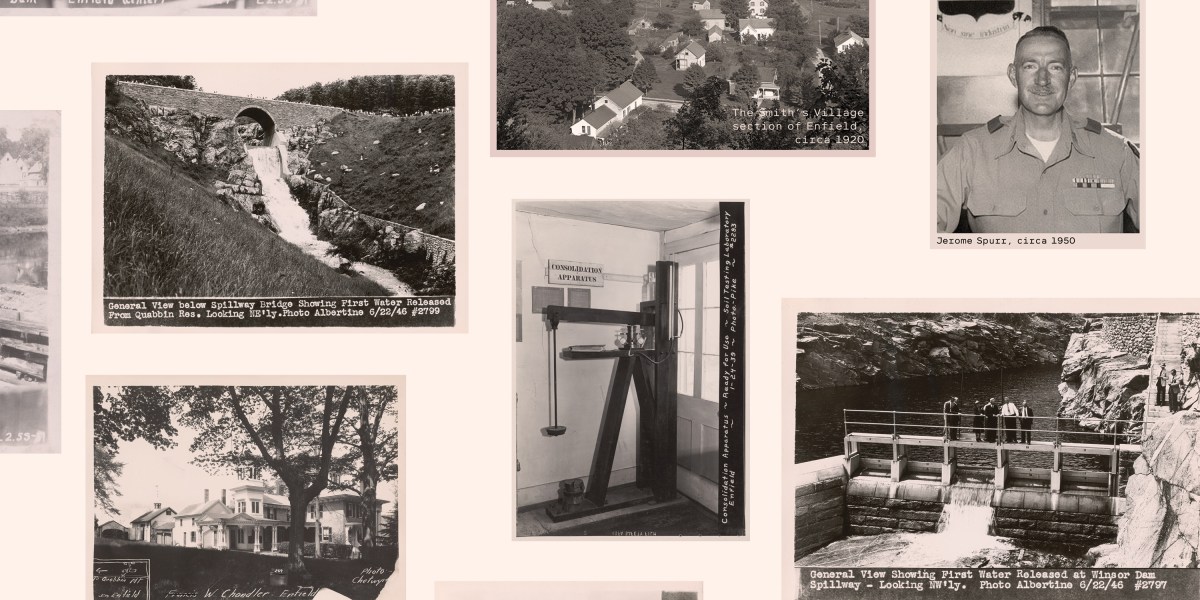

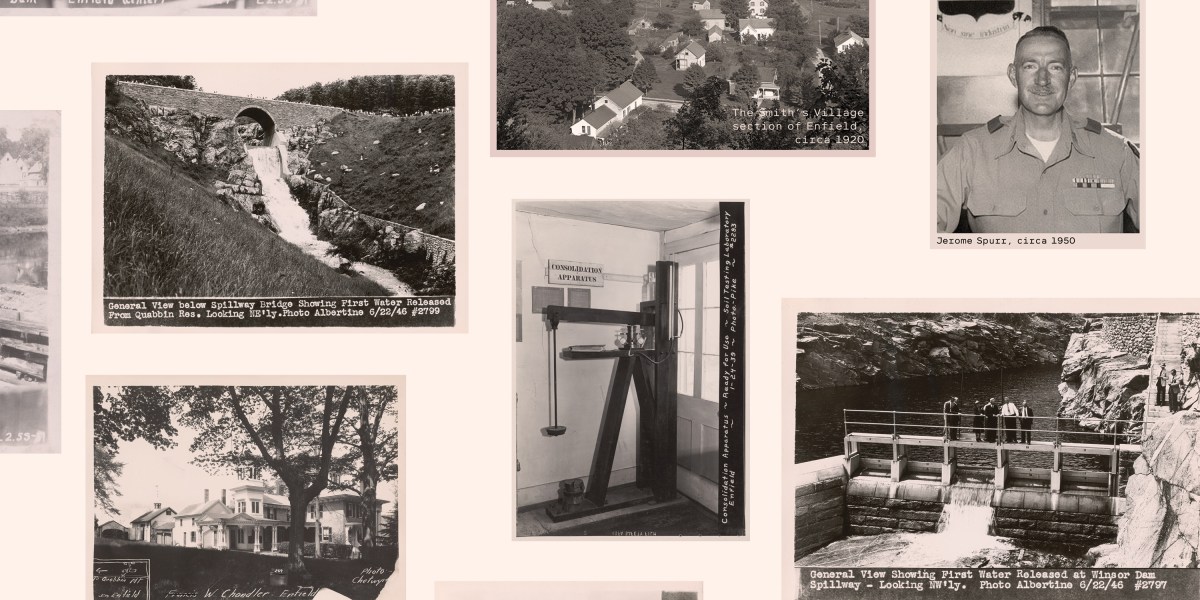

Jerome Jerre Spurr, a senior at MIT, had not paid much attention to articles in the Boston Globe regarding the planned new reservoir for Western Massachusetts. He was able to meet Frank Winsor in person in 1927, less than a month after his graduation.Winsor visited MIT personally to recruit engineering students to build the reservoir. It is the largest world-wide water source, measuring 18 miles in length and six miles wide. Spurr was born in Dorchester and had a bachelor's degree in civil engineering, with a focus in soil sciences. He had also been mentored in soil sciences by Karl Terzaghi. But he didn't think about the next step. Winsor chose him immediately to lead a contingent to the Swift River Valley, where the future reservoir would be built.Spurr and six other MIT grads headed for Enfield, Massachusetts. This is the largest of four small communities on the valley floor, 65 miles west from Cambridge. Although they may have been able to comprehend the importance of their arrival intellectually they did not feel it in the flesh. They would be responsible for the destruction of the entire valley. Every building would be demolished, every grave excavated, every tree and farm would be cut down to make way for new, clean water. The four towns of Swift River ValleyEnfield and Greenwich would be erased from the map, as if they never existed. They would be replaced with 412 billion gallons water. Nearly 2,500 people would be forced to leave the four doomed cities and parts of their surrounding areas.Locals were suspicious of the college men wearing natty clothes and driving fast cars. The valley was home to many young men who were looking for better work.The Swift River Valley was not the first to be invaded by the MIT engineers. Nor were residents of Enfield and Dana Greenwich forced to flee. Native Americans had lived in the valley's many streams, lakes, and ponds for centuries.It took a lot of engineering work to build the reservoir. This included digging the Quabbin Aqueduct, 24.6 miles long, between the new reservoir, and the Wachusett Reservoir northeastern of Worcester (the longest tunnel in the world at that time); orchestrating the flow of water to Boston through an 80-mile network made of concrete pipes and tunnels; digging the Winsor Dam and Goodnough Dike in the middle of the reservoir to purify the Swift River water by circulating it; digging the Daniel Shays Highway Route 202 around the reservoir's; and reforesting, in Quabbin Park, as well as well as part of the Quabbin Reservation.This map shows the potential impact of the reservoir on the Swift River Valley. DIGITAL COMMONWEALTH ARMIVESFirst, much surveying had to be done. Each piece of property within the valley and every acre with water and woodland had to be photographed and documented. New college graduates were assigned to surveying groups and began to travel across the valley using their equipment. They often used axes to cut through brush. Spurr was first a rodman, then he became an instrument man. He is the highest-ranking assistant to a surveying team and assists the foreman in completing surveys and blueprints.Spurr enjoyed the hard work of the outdoors, but he was disappointed by the antipathy of the locals. Many refused to accept the young engineers as boarders in Enfield, the home of most engineers. Spurr moved between many homes, including one in which the engineers and their landlords had dinner together every night. Spurr decided that he would prefer to live alone, and rented a farmhouse from Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission. The commission purchased the property from a valley resident who was moving to towns outside of the proposed watershed. Spurr and other engineers spent the day in the Chandler House, a large white Victorian mansion that is the size of small hotels. He knew he would be staying in the valley for at most eight years more so he started renovating the farmhouse during his free time.Spurr quickly rose from instrument man to deed analyst. N. LeRoy Hammond was impressed by Spurr's analytical abilities and promoted him to head the Enfield Soil Division with a staff that included five.The engineers had to test local soil every day as construction of the Winsor Dam accelerated. The hydraulic fill dam, which measures 40 feet in width, was built on top of a row concrete caissons that were attached to the bedrock. It was made from recycled earth and rock from the valley. Swift River water was piped up to the construction site. The water then ran down the core and the fill was expected not to withstand the many millions of gallons against it.To monitor construction, engineers had constructed an artificial lake at the dam's western base. It was equipped with pontoon boats. Spurr stated in 1987 that with each layer of fill, the potential existed for sand spits from the beach - the strip of land located between the dam and artificial lake - to penetrate the core making it permeable. If bits of the core material were to extend into the beach, it could cause planes of weakness and eventually slide. Spurr stated that the fill was unstable by itself. It had the consistency of molasses. He and his soil sample party tested both the dams cores and the soil on the beach each day. They collected 15-pound bags of soil and drove them back to the Chandler House for analysis.The core samples were also analysed by the researchers. Terzaghi described Spurr's help in developing a core sampling device. It consisted of a tube with a piston and was connected to Terzaghi's rod through the extension. The sampler could then be pushed into the core until it reached the desired depth. After the tube contents were removed from the core, the sample party filled pint-jars with their contents and marked them with the depth and location. Contractors built observation wells to allow Spurrs' team to climb down the dam and collect samples. Spurr stated that fast-paced analysis in high-stakes situations was difficult work because the technology and procedures were new. Spurr was installing them and flagging any problems. The head dam engineer would then take the necessary steps to make sure the structure is strong enough to hold the water.Spurr stated that it was important to maintain a current testing operation. He said that a pervious dam would be equivalent to millions of gallons molasses, which is a terrifying image for anyone who remembers the Great Molasses Flood of 1919 in Boston, which killed 21 people.The economic impact of the project had a devastating effect on the people living in the valleys. Many people sold their homes to the commission at Depression-level prices. This left them with very little to show for what was often many generations of hard work. Many were no longer able or able to farm and had to accept any job they could, often with the same commission that forced them from their homes.Spurr (second row, right) was a member of the Grand March that took place at the 1938 farewell ball. DEPT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES (W.E.B. DU BOIS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY of MASSACHUSETTS AmherST (PROGRAM).Spurrs work took up most of his time, even on Saturdays. But he felt a sense of responsibility to help those whose lives and livelihoods were being irrevocably altered. He tried to be useful in the community. He started Sunday school. He founded a Boy Scout troop. Anna Chase, a Vermonter who came to Enfield to be a teacher, was his first wife. She sang in the church choir. Anna Chase was the first president of the Quabbin Club women's social organization. She also played the piano at funerals for those who couldn't afford it, Spurr says. As the chapter Worshipful Master, he was also the treasurer. The Enfield Masons roster had as many local engineers as it did engineers in the mid-1930s. Spurr, along with many other engineers, had already become part of the community. They founded jazz bands, joined baseball teams, and even married local girls. In 1934, Christmas was approaching. Few families had the money to purchase decorations. Several of them stepped in and bought electric Christmas lights. They strung them up on a large tree that they built in the basement of a burned-down commercial building. The electric company was also persuaded to switch the power back on after New Years Day. It was the town tree, and could be seen all around the valley.The final phase of dam construction was about 11 years after Spurrs arrived in Enfield. Despite the interference and graft of the highest state levels, the Quabbin project was completed on time and within budget. The Enfield Volunteer Fire Department hosted a farewell ball as the four Swift River Valley towns were set to be disintegrated at midnight on April 28, 1938. On April 27, thousands of people dressed in black mourning or formal wear arrived at Enfield Town Hall. This brick building was designed for 300 people. Spurr, as is his rightful place in the community was at the front of the line for the ball's Grand March. He cried with the rest of the crowd when the clock struck midnight and Auld Lang Syne began.In 1939, the Swift River Valley was set for flooding. By mid-1938, the area had lost its crops and was devoid of schools, stores, and churches. Spurr had planned to buy his Enfield home and move it to another place before the floods rose. However, a September 1938 hurricane destroyed his telephone, electricity and plumbing. None of these would be restored. He and his wife, along with their son, moved to Wellesley. Then he started work on the Quabbin's next stage: pressure tunnels that carried water from the Wachusett Reservoir to Weston's Norumbega Reservoir. He was the last engineer out of the valley.Spurr resigned from the commission as an assistant professor of military tactics at MIT in 1941. He also became the head of the MIT ROTC Engineering Unit. In his spare time, he lectured about the Quabbin Reservoir using movies he and others had made on expensive Technicolor film. After serving in Poland and Austria in the Army Corps of Engineers he tried to start a Boy Scout organization in Turkey, while also supporting US military operations there. He retired from the military in 1958 and lectured occasionally on Quabbin construction history. He also taught a class at Wentworth in soil sciences. Spurr, now 83, was once again at the head the Grand March when the farewell ball in Amherst was re-created to commemorate the 50th anniversary the death of Swift River Valley.Spurr, a mentor to a valley native, introduced Spurr as an engineer who had been trained by Spurr in 1980s. Spurr then walked onto the auditorium stage to a standing ovation. In his Boston gentleman's accent, Spurr said that everything you heard was exaggerated. I am grateful for all the kind words and compliments that have been given to me. I don't know if they will be met or not but I will try.The old MIT engineer then launched into a technical complex, 90-minute lecture about engineering work that he had completed half a century ago and still knew by heart.Elisabeth C. Rosenberg, the author of Before the Flood, Destruction, Community and Survival in the Drowned Townships of the Quabbin is due out by Pegasus Books on August.