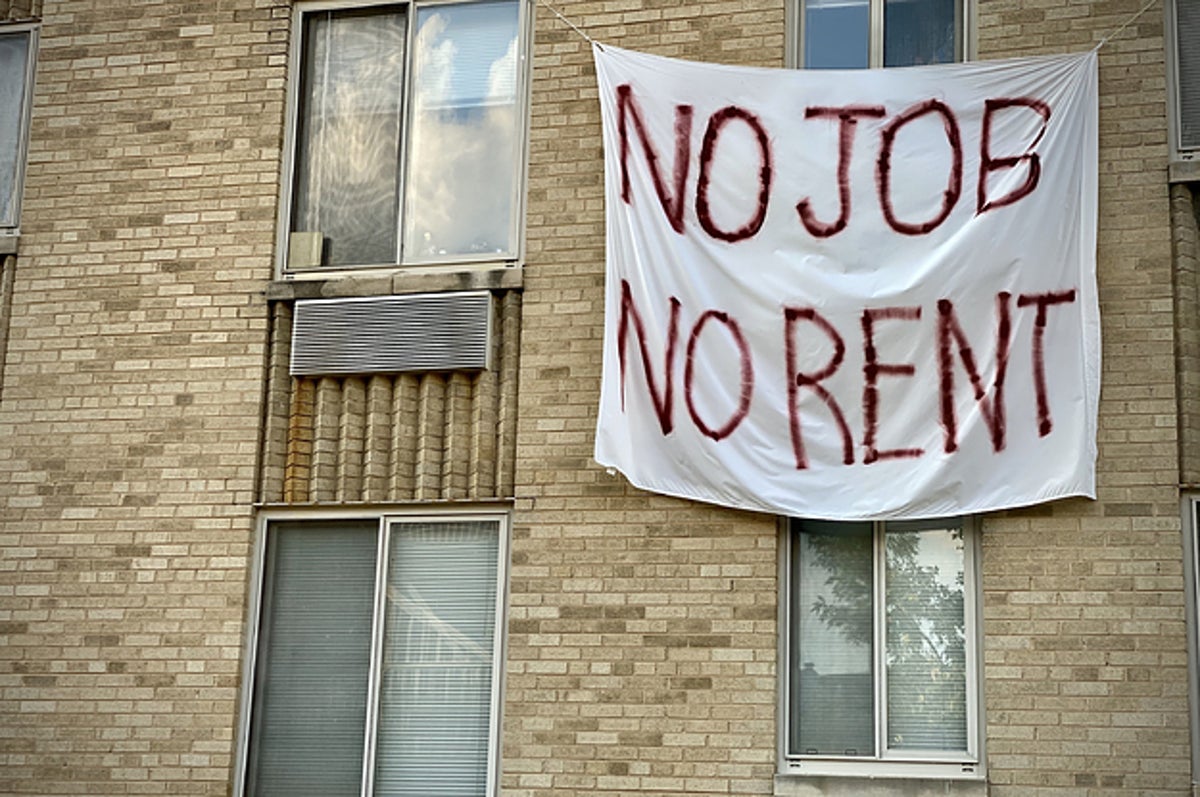

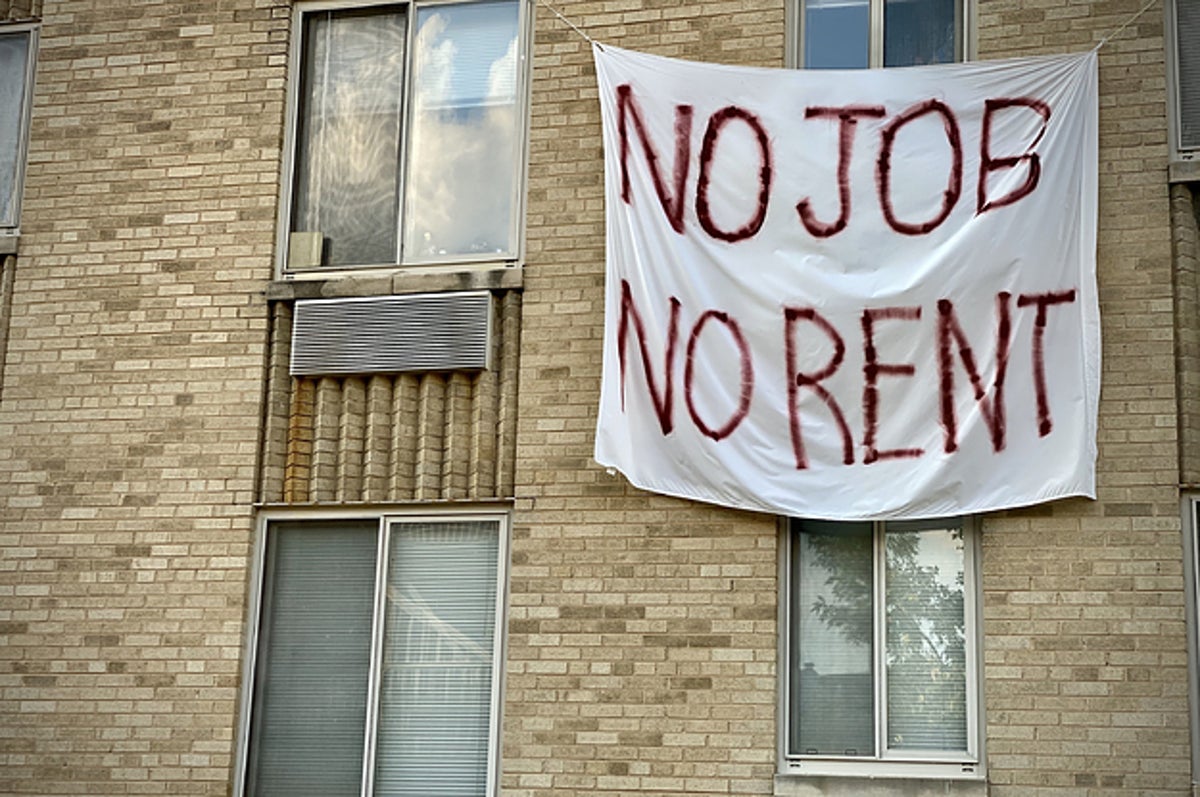

WASHINGTON After the US Supreme Court denied Tuesday's request to end it abruptly, the federal moratorium on evictions is still in place. Renters across the country have relied upon this policy to alleviate financial hardships due to the coronavirus pandemic.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had set June 30 as the expiration date. However, near the end of June, the CDC extended the deadline to July 31. The 54 order by the justices denied that they would intervene in a continuing legal battle between landlord and real-estate industry groups, which was based on the policy. The Supreme Court's order will mean that the moratorium will remain in effect for the time being and that the case will be continued in the lower courts.Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and the courts liberal wing Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan joined forces to keep the moratorium in place for another month. According to the order, the remaining conservative members of the court, Justices Clarence Thomas Jr., Samuel Alito Jr. and Neil Gorsuch, would have lifted an order from a lower court that had kept the moratorium in effect while legal challenges were pending.Kavanaugh submitted a concurring statement of one paragraph in which he stated that he was with the plaintiffs that the moratorium was illegal, but that the CDC's decision to state that the most recent extension would be the final convinced him that the court should not intervene now.Kavanaugh wrote that the CDC intends to lift the moratorium within a few weeks. This will also allow for more efficient and orderly distributions of congressionally appropriated rental aid funds.The real estate industry associations that sued didn’t receive the immediate order lifting their moratorium, but the National Association of Realtors released statements calling it a "massive victory for property rights" since they expected the matter to be resolved soon. Charlie Oppler, the president of the group, stated that the order "keeps tenants in place for another month while providing clarity for struggling housing providers.""With the pandemic subsiding and the economy improving it is time for the housing sector back to its former healthy function. Oppler stated that property owners also deserve this clarity from the federal courts regarding American property rights to avoid future financial disasters.A spokesperson from the CDC or the Justice Department did no immediate respond to a request for comment.According to the latest moratorium order by the CDC, there are 43 million renters living in the United States. The Census Bureau based on continuous pulse surveys found that approximately 4 million people could be at risk of being evicted or foreclosed in the next two-months if they aren't current on their rent and/or their mortgage.When the original moratorium was issued in September, the CDC's role in freezing evictions in the aftermath of the pandemic started. The 120-day moratorium that Congress had previously included in COVID-19 relief legislation was still in effect, but it expired in July 2020. According to the CDC, keeping people in their homes was part the public health response to the pandemic. Evictions increase the chance that people will move in with relatives or friends or to shelters for homeless people or other congregate living areas, which can undermine efforts to stop the spread of the disease.The first CDC moratorium was extended by Congress through January. It was then extended three times more by the CDC through March, June and July. The industry groups sued had asked the Supreme Court for assistance on June 3. After several weeks of inaction, the justices failed to act on the petitions. The industry challengers submitted a June 23 letter reiterating their request for intervention before the CDC granted another extension.The Supreme Court case began in Washington DC's federal district court. There, a number of real estate trade and rental property managers sued the CDC.The case revolved around a section in the Public Health Service Act which gives the CDC the power to issue regulations to prevent the spread of communicable disease. The law lists specific remedies that the CDC could order, including inspection, fumigation and disinfection. It also covers pest extermination, sanitation, pest control, destruction of animals and articles found to have been infected or contaminated enough to cause serious illness to humans. However, the government argued that the law gives the CDC much greater authority to prevent diseases spreading.The challengers were supported by Dabney Friedrich, a US District Judge. In an opinion she wrote in May that the pandemic was a grave public health emergency that presented unprecedented challenges to public health officials. However, Friedrich did not limit her order to only the plaintiffs. She issued a nationwide ruling.Friedrich wrote that it is the responsibility of the political branches to evaluate the merits and limitations of policies designed to stop the spread of diseases, regardless of whether there is a global pandemic. The Court must answer a narrow question: Does the Public Health Service Act give the CDC legal authority to impose a national eviction moratorium. It doesn't.Friedrich granted the request of the government to pause her ordeal while the DC Circuit was asked to intervene. On June 2, the appeals court maintained Friedrich's decision under pause. Although it was not a final decision on the merits, the three-judge panel stated that they believed that the government would win the end. The Supreme Court was asked to intervene by the challengers the day after.Landlords and industry groups have filed similar lawsuits in different courts challenging the federal eviction ban. However, the results were mixed. A federal judge in Tennessee ruled the moratorium unlawful in March. However, instead of removing it completely, he ruled that it could not be enforced in his western district. While the Justice Department appealed the judge's decision, the US Court of Appeals for 6th Circuit denied them the request to pause the order.In October, a federal judge in Atlanta sided in favor of the CDC. The challengers appealed the decision to the 11th Circuit. The appeals court denied a request to stop the moratorium, heard arguments on May 14, and has yet to make a decision. A federal judge in Louisiana sided in December with the government, while a Texas federal judge sided in February with the challengers. In March, a federal Ohio judge sided in March with the challengers; all three cases are currently pending before the appeals courts.DC was the only case before the Supreme Court that involved an order that would have ended the nationwide moratorium.Although the latest order does not set any precedents that would be applicable in these cases as they progress, it does send a message about the likely response of the justices to any future attempts in the next month for the court to intervene on an urgent basis.