The number of deaths in the United States through July 2020 is 8 percent to 12 percent higher than it would have been if the coronavirus pandemic had never happened.

That's at least 164,937 deaths above the number expected for the first seven months of the year - 16,183 more than the number attributed to COVID-19 thus far for that period - and it could be as high as 204,691.

When someone dies, the death certificate records an immediate cause of death, along with up to three underlying conditions that " initiated the events resulting in death." The certificate is filed with the local health department, and the details are reported to the National Center for Health Statistics.

As part of the National Vital Statistics System, the NCHS then uses this information in various ways, such as tabulating the leading causes of death in the United States - currently heart disease, followed by cancer.

Sometime this fall, COVID-19 will likely become the third-largest cause of death for 2020.

To calculate excess deaths requires a comparison to what would have occurred if COVID-19 had not existed. Obviously, it's not possible to observe what didn't happen, but it is possible to estimate it using historical data.

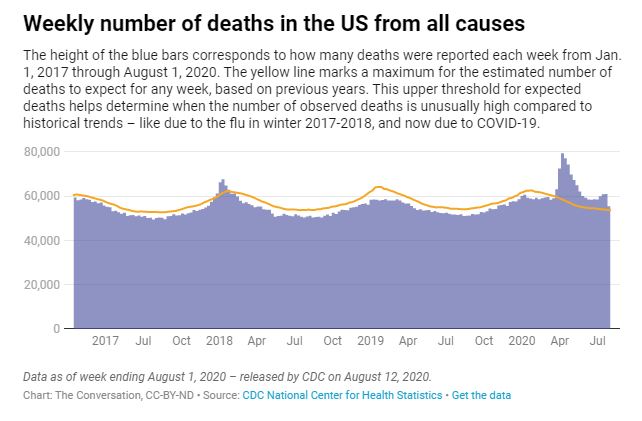

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does this using a statistical model, based on the previous three years of mortality data, incorporating seasonal trends as well as adjustments for data-reporting delays.

So, looking at what happened over the past three years, the CDC projects what might have been. By using a statistical model, they are also able to calculate the uncertainty in their estimates. That allows statisticians like me to assess whether the observed data look unusual compared to projections.

The number of excess deaths is the difference between the model's projections and the actual observations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also calculates an upper threshold for the estimated number of deaths - that helps determine when the observed number of deaths is unusually high compared to historical trends.

Clearly visible in a graph of this data is the spike in deaths beginning in mid-March 2020 and continuing to the present. You can also see another period of excess deaths from December 2017 to January 2018, attributable to an unusually virulent flu strain that year.

The magnitude of the excess deaths in 2020 makes clear that COVID-19 is much worse than influenza, even when compared to a bad flu year like 2017-18, when an estimated 61,000 people in the US died of the illness.

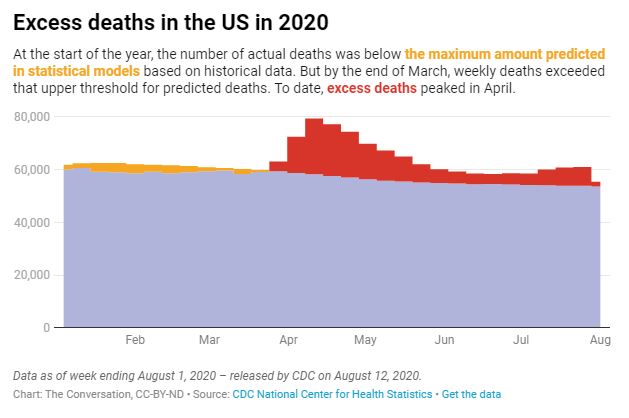

The large spike in deaths in April 2020 corresponds to the coronavirus outbreak in New York and the Northeast, after which the number of excess deaths decreased regularly and substantially until July, when it started to increase again.

This current uptick in excess deaths is attributable to the outbreaks in the South and West that have occurred since June.

It doesn't take a sophisticated statistical model to see that the coronavirus pandemic is causing substantially more deaths than would have otherwise occurred.

The number of deaths the CDC officially attributed to COVID-19 in the United States exceeded 148,754 by August 1.

Some people who are skeptical about aspects of the coronavirus suggest these are deaths that would have occurred anyway, perhaps because COVID-19 is particularly deadly for the elderly.

Others believe that, because the pandemic has changed life so drastically, the increase in COVID-19-related deaths is probably offset by decreases from other causes. But neither of these possibilities is true.

In fact, the number of excess deaths currently exceeds the number attributable to COVID-19 by more than 16,000 people in the US What's behind that discrepancy is not yet clear. COVID-19 deaths could be being undercounted, or the pandemic could also be causing increases in other types of death. It's probably some of both.

Regardless of the reason, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in substantially more deaths than would have otherwise occurred ... and it is not over yet.