A new study identifies a flight in February on which spread of Covid-19 might might have occurred. It's being used by airline unions to call for a 'national mask policy' on flights, even though all U.S. airlines already require masks, and it's being used to attack President Trump over masks.

It's an interesting and detailed look at a single flight on which 100 passengers originated in Wuhan, China. It's also not the first flight where there were suspected cases of Covid-19 spread on a plane. A March 1 Vietnam Airlines flight from London Heathrow to Hanoi carried passengers who later tested positive for the virus.

Given the number of people in the world confirmed to have been infected by SARS-CoV-2, and the number of flights that have taken place throughout the pandemic I'd be surprised if there hasn't been a single incident of spread on a plane somewhere during that time. What's most striking is how few we've been able to find, not just in the U.S. but worldwide, regardless of what you think of variance in contact tracing capabilities in different locations. (A $295 million contact tracing contract in Texas has generating basically no actual work.)

In each of these instances of suspected inflight spread what you want to look for is whether it's likely the people on the flight were infected elsewhere.

These things may suggest that it's not a case of a person being infected, and people near that person catching the virus.

If you see clusters on a plane of unrelated people sitting in rows near each other, it may also be that they picked up the virus waiting in the gate area before the flight, or on the jetway (since nearby rows tend to be boarded together). The reason that matters is because knowing where during travel spread occurs leads to different policy responses.

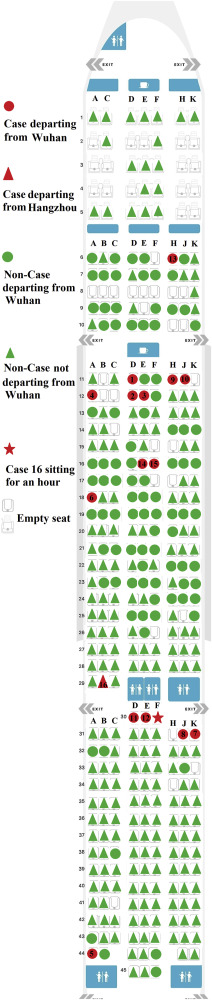

Researchers studied a 4:30 p.m. Singapore Airlines Boeing 787 flight from Singapore to Hangzhou on January 24, 2020 which had 335 passengers on board along with 11 crew. 100 passengers "had visited Wuhan" - arriving in Singapore 5 days earlier - and containment procedures were in place on arrival, not least of which because "several passengers had already developed fever or upper respiratory infection symptoms" (suggesting that their exposure happened prior to the flight).

These passengers tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 the following morning, and ultimately 16 passengers from the flight would test positive (6 of whom were asymptomatic). The final two cases were identified on February 2, 9 days after the flight.

If the passenger who hadn't traveled to Wuhan did pick up the virus inflight, what's remarkable is that with 15 people that had been in Wuhan in January ultimately testing positive for the virus only one other person on the aircraft got it. What's remarkable is the lack of spread, rather than that there's spread, considering the number of infected persons on board.

While the paper is being taken as proof of inflight spread the researchers actually conclude only that transmission of the virus "may have occurred during the flight" though it looks like "the majority of the cases..could not be attributed to transmission on the flight but were associated with exposure to the virus in Wuhan or to infected members in a single tour group."

With less talking (fewer respiratory droplet emissions), HEPA air filtration, and a high rate of cabin air refresh many mainline passenger jets are safer from a virus spread perspective than dining inside a restaurant or doing any number of other activities that are permitted in many states. That is likely even more the case with mask enforcement becoming near-universal and much more common by commercial airlines.

Nonetheless it's difficult to imagine any activity done at scale that won't see some spread of the virus. Absent a 'full Wuhan' lockdown policy, passenger cabins are probably low on the list of concerns to address.

Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding attributes at least one case on the flight to lack of mask wearing and that's an important takeaway, because if spread happened on board it may be that a properly worn quality mask would have prevented it.

That's a separate matter from travel itself, whether someone with the virus might bring it with them to an area that currently has low infection and generate an outbreak at their destination. That's why I've suggested that the ban on Europeans coming to the U.S. came too late (but no longer makes sense) and why I've been surprised to see relatively few limits on domestic travel. Much of the spread being experienced in the country today likely originates with people who had it in New York (and to a lesser extent on the West Coast) and traveled inland.