A breach of judicial ethics may have prevented up to 1 million Floridians from voting in November. On July 1, a federal appeals court lifted an order that had blocked Florida from imposing a poll tax on people convicted of felonies. The U.S. Supreme Court then declined to step in. If two judges appointed by President Donald Trump had complied with the judicial Code of Conduct, Florida's discriminatory and unworkable poll tax might well have remained blocked through Election Day. And Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee are now demanding that these judges explain their justification for flouting their ethical duties.

The two judges in question, Barbara Lagoa and Robert Luck, have served on the 11 th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals since late 2019. Trump elevated them to the 11 th Circuit from the Florida Supreme Court, where each had served for less than a year. During their brief time on the state court, the justices heard a case about a constitutional amendment passed in 2018 that restored voting rights to Floridians who had been convicted of a felony. The amendment granted suffrage to individuals who have completed "all terms of their sentence including parole or probation." Florida Republicans then dramatically limited who could benefit by requiring ex-felons to pay all court-imposed fines and fees before regaining their right to vote. Their scheme essentially imposed a poll tax-or, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor later put it, a "voter paywall."

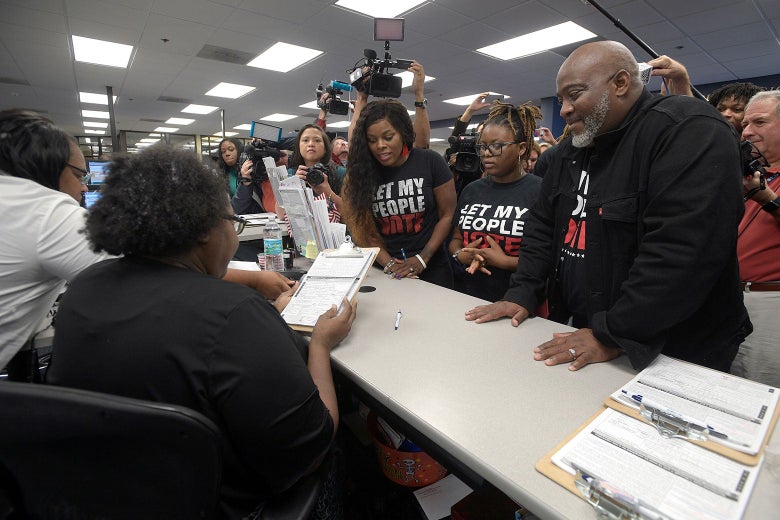

Because Florida funds its criminal justice system by charging defendants a mind-boggling array of fees, this paywall would prevent a huge number of people from voting in 2020. Between 750,000 and 1.1 million Floridians are believed to have court debt, though the state does not keep track of these records and cannot identify how much money most individuals actually owe. To shore up the scheme's legality, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis-a vocal opponent of the voting rights expansion- asked the Florida Supreme Court to provide a definitive interpretation of the law.

The Florida Supreme Court held oral arguments on the matter, in which Lagoa and Luck energetically participated. Lagoa was particularly combative: Sounding more like an advocate than a jurist, she repeatedly argued that voters understood the amendment to encompass court fines and fees. At one point, she even read aloud a Miami Herald op-ed that allegedly supported her position. "I have reams here of op-ed pieces and editorials from different papers all over the state of Florida," Lagoa proclaimed, "that made it clear" the amendment included fines and fees.

But neither Lagoa and Luck ever formally ruled in the case. They joined the 11 th Circuit shortly before the Florida Supreme Court handed down its decision in January declaring that the state constitution permitted a poll tax on ex-felons. Nonetheless, both judges almost certainly discussed the case with their colleagues and voted on the outcome. Moreover, one or both judges may have participated in the initial stages of drafting the opinion.

Judges who have participated in a case are required by the judicial code of ethics to recuse themselves from hearing related matters. But Luck and Lagoa, newly appointed to the 11 th Circuit, got another chance to weigh in on Florida's law. After the state Supreme Court handed down its ruling, U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle ruled that the poll tax violated the federal Constitution by conditioning the right to vote on wealth.

Hinkle also found that Florida had no idea how much court debt was owed and no way to find out. In response, he crafted an injunction that ensured formerly incarcerated Floridians could vote if they were too indigent to pay court fines and fees or if the state could not say how much they owed. Hinkle's ruling had huge implications for the November election: If upheld, it could grant roughly 1 million Floridians access to the ballot box, potentially turning the swing state blue.

The federal judiciary largely relies on appellate judges to police their ownethics.

But Hinkle's ruling was not upheld. Instead, the 11 th Circuit blocked it by exploiting an exceptionally rare procedural maneuver. In the federal judiciary, virtually every appeal is heard first by a three-judge panel; occasionally, the full court, sitting en banc, reviews a case first heard by a panel. This time, though, the 11 th Circuit agreed to hear the case en banc first, bypassing the three-judge panel entirely. In the process, the full court swept away Hinkle's injunction without any explanation.

When a court manipulates procedural rules to alter the composition of a swing state's electorate in the runup to a presidential election, it had better be on sound ethical footing. The 11 th Circuit was not. Given the composition of the court, it's likely that Lagoa and Luck cast the decisive votes to lift Hinkle's injunction.

Their participation is deeply troubling. Federal law requires a judge to recuse from "any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned." And under the Code of Judicial Conduct, judges must recuse from a case when they have "participated as a judge (in a previous judicial capacity)" at "other stages of litigation." Lagoa and Luck plainly "participated" in the litigation around Florida's poll tax at "other stages of litigation": They heard arguments about the proper interpretation of the law upon which the federal dispute turns. Their impartiality can certainly be questioned in light of their pontifications about the poll tax scheme on the Florida Supreme Court. Thus, both should have promptly recused from the federal case.

The 11 th Circuit still has to hear arguments and decide this case on the merits. The plaintiffs have urged Lagoa and Luck to recuse themselves from further consideration of the case. All 10 Democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee also sent both judges sharp letters on Tuesday demanding an explanation for their non-recusal. These letters noted that Luck told the committee he would recuse "from any case where I ever played any role." Lagoa promised to "recuse myself from any case in which I participated as a justice on the Supreme Court of Florida." There is no real question that the federal challenge to the state's poll tax is a case "involving" the Florida Supreme Court's decision on the matter.

Unfortunately, no reliable mechanism exists to force either judge's recusal. The federal judiciary largely relies on appellate judges to police their own ethics. Most do follow the rules; in fact, two judges on the 11 th Circuit recused themselves from the en banc vote: Robin S. Rosenbaum, a Barack Obama appointee, and Andrew Brasher, a Trump appointee. Rosenbaum did not explain her recusal but presumably has a relationship with one of the many lawyers on the case. Brasher did not participate in the en banc vote because he had joined the court just hours before. He has since recused himself from the case altogether because his former employer, the Alabama Attorney General's Office, filed an amicus brief.

If Lagoa and Luck had recused too, the court would've been divided 4-4 between Democratic and Republican appointees. The deadlocked court would have left Hinkle's injunction in place as the case progressed through the normal appeals process. That process would have taken months, and the court probably wouldn't have reached a decision by November. As a result, Floridians with outstanding fines and fees could still have participated in the upcoming election.

If the 11 th Circuit had kept Florida's poll tax on ice, perhaps the Supreme Court would have stepped in to reinstate it. Or maybe the justices would have hesitated to reverse the appeals court and take ownership of the mass voter suppression that would follow. Either way, at least Floridians would know that the judges respected minimal ethical standards. But Lagoa and Luck have simply waved those standards away. They have tainted this litigation with their own ethical breaches, making it even more difficult to swallow the 11 th Circuit's peculiar and disturbing treatment of this case.

For more of Slate's news coverage, subscribe to What Next on Apple Podcasts or listen below.