Karaoke is one of Japan's most ubiquitous worldwide exports. But who invented the first machine that let you sing along to backing tracks of popular hits?

As author Matt Alt writes in his new book Pure Invention, karaoke was independently invented at least five different times in Japan. A musician-businessman named Daisuke Inoue has often been credited as the inventor of the first karaoke machine in 1971, but it was actually Shigeichi Negishi, owner of an electronics factory, who first invented the machine in 1967.

During the research for Pure Invention, Alt tracked down the 95-year-old Negishi, visiting him at his home to get a first-hand look at his invention, the Sparko Box, and learn how karaoke first came to be.

For the entrepreneur Shigeichi Negishi, singing was both a way to unwind and to pump himself up for the day to come. He started every morning with a long-running radio sing-along show called, straightforwardly enough, Pop Songs without Lyrics-a sort of nationwide precursor of karaoke served up over the airwaves. One day in 1967, Negishi kept singing as he walked into the offices of Nichiden Kogyo, his electronics-assembly firm, which built 8-track tape decks for other companies in the suburbs of Tokyo. His head engineer gently ribbed the boss for his crooning. And that, says Negishi, is when inspiration struck.

"I asked him, 'Can we hook a microphone up to one of these tapedecks so I can hear myself singing over a recording of Pop Songs without Lyrics?'"

"'Piece of cake, boss,' he told me."

Negishi's request arrived at his desk three days later. The engineer had wired a microphone amp and a mixing circuit to a surplus 8-track deck. Negishi turned it on and slotted in an instrumental tape of " Mujō No Yume " ("The Heartless Dream"), an old favorite from the thirties. His voice came through the speakers along with the music-the first karaoke song ever sung. "It works! That's all I was thinking. Most of all, it was fun. I knew right away I'd discovered something new." He told his engineer to build a case for it, wiring in a coin timer they had lying around for good measure. He instantly grasped that this was something he could potentially sell.

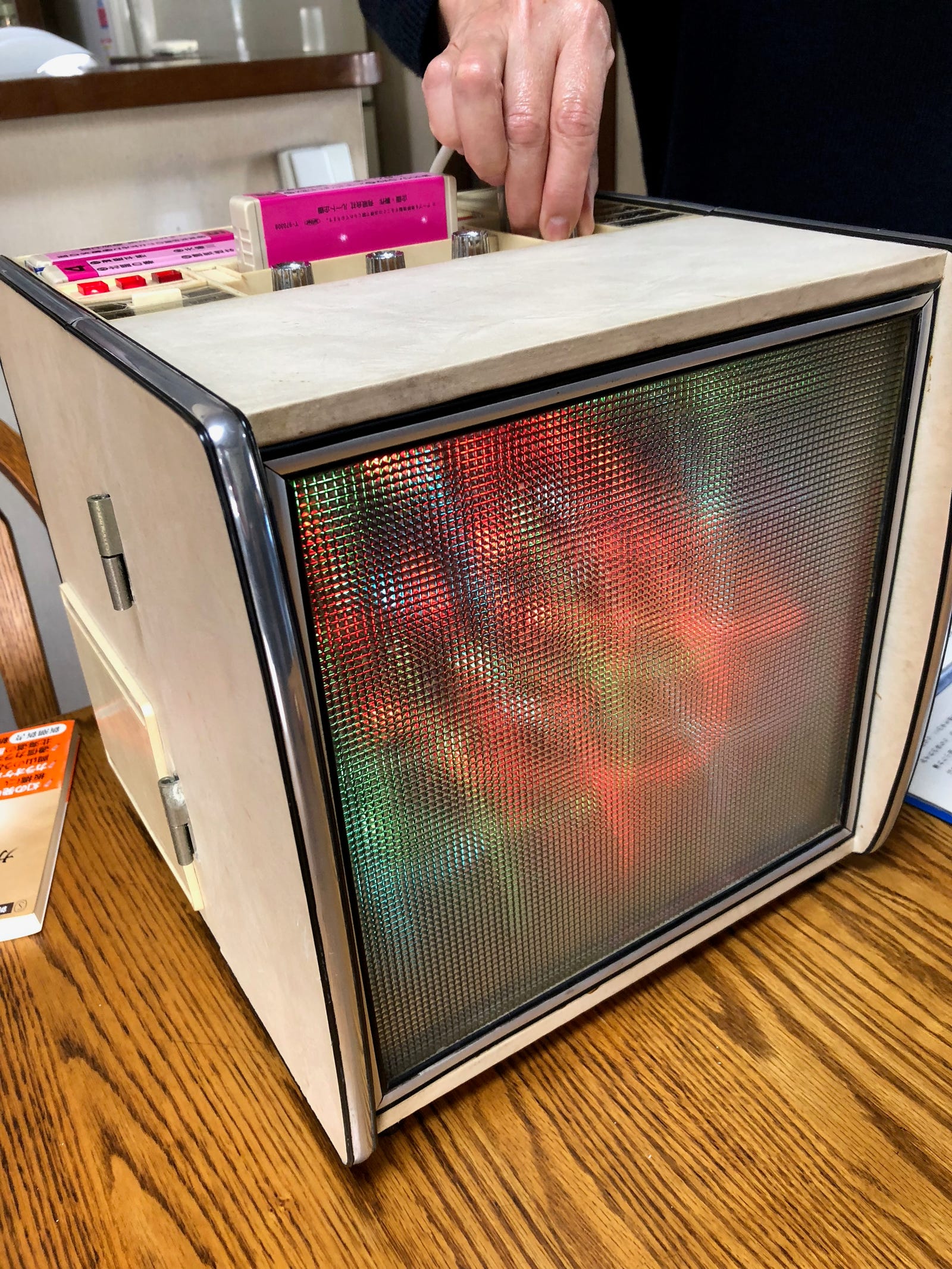

He called his baby the Sparko Box. As eventually finished, it was a cube about a foot and a half per side, edged with chrome and finished with a beige Formica-like material of the sort one might see on the counter of a sixties luncheonette. There was a rectangular opening for a tape on top, surrounded by knobs for controlling volume, balance, and tone, flanked by a microphone jack and a hundred-yen coin slot. It took its name from another Negishi innovation: Its front panel was a sheet of corrugated translucent plastic hiding a constellation of multicolored lights that strobed in time with the music.

But, for now, all he had was his mad-scientist prototype. He carried the components home that evening as a surprise for his wife and three children. One by one, they took turns singing over the tape. His daughter, who was in middle school at the time, still recalls the shock and thrill of hearing her voice coming through a speaker together with music.

Advertisement You can skip ad after 1 second

You can go to the next slide after 1 second

This was a true moment: Negishi had convened the world's first karaoke party in his kitchen. Soon, Negishi would print up songbooks, with lyrics for singers to read along with as they sang. For now, it was just a tape deck, an amplifier, a speaker, and a microphone. Yet something had changed, even if only in this one kitchen for the moment. Adding your own vocal track to a musical backing was no longer something reserved for professional performers.

Negishi ran a factory. His customers were big corporate concerns. He didn't have the experience or infrastructure to market and sell products to consumers himself. As he had with his other inventions, he sought out a distributor. In the meantime he approached a friend who worked as an engineer at the national television channel, NHK. He might know where to find more instrumentals of the sort they used for Pop Songs without Lyrics. He'd need as many as he could lay his hands on to make the venture worthwhile.

"He said, 'Karaoke. You want karaoke tapes.' That was the first time I'd heard the word. It was an industry term, you see. Whenever a singer would perform out in the countryside, they'd use instrumental tapes, because it was a real pain to get a full orchestra out there with them. So they'd perform with a taped backing track instead-with the orchestra pit 'empty.' That's what karaoke means."

Negishi found a distributor. "But he wouldn't let me call it a karaoke machine! Said karaoke sounded too much like kanoke," the word for a coffin. And so the Sparko Box went out into the world under a variety of other brand names: The Music Box, Night Stereo, and Mini Jukebox, among others.

Negishi also knew he couldn't rely on NHK to supply music for an actual product, so he turned to yet another friend, who ran a tape-dubbing business. "Instrumental recordings were actually easy to find back then," recalls Negishi. They were sold for use in dance halls, where a hired performer would sing over them, or purchased by those who simply really enjoyed singing. Negishi picked a few dozen of the top songs for his friend to record onto custom 8-tracks.

Before the Sparko Box, there wasn't any karaoke. "Back then, if you wanted to sing, the only way to do it was with nagashi "-wandering guitarists who plied their trade from bar to bar, charging patrons for performances-"and those guys were expensive!"

The Sparko Box promised to bring sing-alongs to the masses, offering up performances for just a hundred yen a pop rather than the minimum thousand yen nagashi charged for a few songs. And therein lay a problem. As Negishi and the distributor demonstrated the singing machines at bars, the owners would grow excited at the prospect of selling songs to their customers-then call back sheepishly the next day asking the men to retrieve the devices, and quickly.

"They'd tell us that their patrons couldn't get enough, and that we should never come back," said Negishi with a sigh. "It was the nagashi! They were complaining. Everywhere we put the box, they'd force the owners to take it away."

After discussing the idea of patenting the Sparko Box, he and his partner decided the cost and headache wasn't worth it; it was, at the time, extremely expensive and time-consuming to obtain a patent. And besides, it wasn't like they had any competition. But that wouldn't be the case for long.